There are many lenses through which we might examine American history. In the spirit of Black History Month, I offer the lens of Hanif Abdurraqib, a poet, essayist, and cultural critic born in 1983 and raised in Columbus, Ohio. His primary lens carries with it a few labels that may be of interest; although great care must accompany the labeling so that we do not find ourselves squeezing people into cultural boxes. However, when the labels polish the lens, they become almost essential.

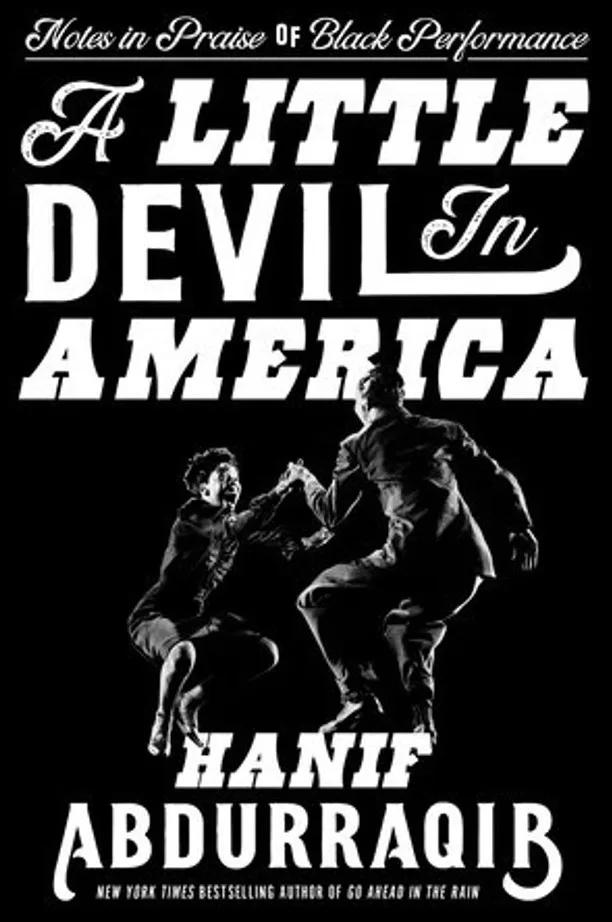

Abdurraqib is Black. He is also a member of Generation Y, a millennial; meaning, he grew up in the first American generation to be raised in an environment where technology and its attendant devices and screens have been a defining feature of daily life. He is also a Muslim. In his book A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance (2021) he shares his reflections on the power of personal creativity and the performance arts to express and explain the racially-influenced nuances of the world in which we live.

In this case, Abdurraqib focuses his unique lens upon the experiences of a number of Black performers spanning several different epochs of American history. And, as is so often the case in our nation’s harsh racial history; the larger significance of these performers is not fully laid bare until taking into account white resistance, white reception, and white reaction. Beyond the many inspiring stories within, it is this Black poet’s commentary on white people that resonates most with me.

Indeed, after speaking directly to the reader in second person, Abdurraqib announces, “By you, I suppose I mean anyone, but let’s say I mean you, non-Black reader or scholar of history.”

Probably the most enduring ripple of Abdurraqib’s effort to examine white behavior in regards to Black performance is drawn from the origins of the minstrel show; characterized most dramatically with the history of white performers donning “blackface” and taking the stage in imitation of their interpretation of what it means to be Black.

Abdurraqib introduces us to John Diamond, an Irish American clog dancer who joined the circus at 17. “[PT] Barnum told audiences that he was twelve,” Abdurraqib writes, “a little white boy with his face painted black, dancing like people had never seen before. And the thing about white minstrelsy is that it was all a lie anyway, so what’s one more.”

Diamond became famous for his dance challenges. This is an ad from the 1840s:

Master Diamond, who delineates the Ethiopian character superior to any other white person, hereby challenges any person in the world to trial of Negro dancing, in all its varieties, for a wager of from $200.00 – $1,000.00.

As it turns out, a Black man named Master Juba took Diamond up on his challenge and won the dance contest prize money time and again. Master Juba becomes Abdurraqib’s stepping stone for his rich anecdotal history of the meaning of Black dance in America.

As to the minstrel show, Abdurraqib reminds us that whatever drove white audiences to applaud blackface in the 1840s seems to be alive and well in the twenty-first century. “Since the election [2016, I presume], white people have been pretending to be Black people on the Internet.”

He suggests that white people may have been doing this all along in one form or another and adds what Master Juba taught John Diamond, “People are [only] talking about it now because the white people who are pretending to be Black people on the Internet are so bad at it.”

Most distressing to Abdurraqib is that most of us, “know [that behaviors like donning] blackface is bad but don’t seem to be entirely sure why. It’s just one of those things that white people shouldn’t do.” While it is healthy for white people to understand that donning blackface is a racist act, Abdurraqib wonders “how far the country has gotten laying down the framework for societal dos and don’ts while not confronting history.” And the history is informed by a single question: Why in the hell was this so funny?

I spent much of my early life laughing at racial jokes… racist jokes. Even today, comedians like Dave Chappelle lay it on thick, although he has often been condemned for it; and Abdurraqib doesn’t hold back in exploring this one. The larger question he asks is not whether or not this stuff is funny, because in many cases it clearly is; but WHY is it funny? I don’t know if I can answer that question, even for myself, but I’m pretty sure a solid answer would enlighten me.

Many of Abdurraqib’s other stories confront us in similar fashion while at the same time celebrating Black performance. In what he calls Black Girl Magic, he tells us of Ellen Armstrong who assisted her magician father, John Hartford Armstrong, “King of the Colored Conjurers,” who had been performing from the early 1900s up and down Atlantic Seaboard. After he died, Ellen defied the gender norms of the day; going on the road with her own show for over 30 years performing in Black schools and Black churches.

She and her father were particularly successful with her tricks in Black churches, Abdurraqib says, because the “audiences… had already placed their faith in the unseen.”

Abdurraqib also shares wonderful stories about performer Josephine Baker, Depression-era dance marathons, performances at the Apollo theater in Harlem, and the manner in which Sammy Davis, Jr. laughed along as “Dean [Martin] and Frank [Sinatra] crack[ed] jokes about his Blackness the way white people at the bar wished they could, a consistent reminder that he was there, but only because they let him.”

While Abdurraqib’s historical reflections raise questions for white readers, it is through his own, more recent, personal experiences with Black performance that we see his millennial props kick in; especially before cable television’s cultural hold on things in the 80s and 90s gave way to the algorithmic and isolationist powers of the Internet.

Yo! MTV Raps delivered a raucous account of Black American life into Abdurraqib’s living room. And then there was the “Black Channel” – BET – that served as a cultural yardstick of sorts; a generation removed from the pinnacle of the 1960s civil rights movement.

For a young Hanif, though, tapping into cable TV’s WGN out of Chicago gave him his best cultural history lesson… by taking a musical ride on the Soul Train. Hosted by Don Cornelius, Soul Train became a hallmark of Black cultural expression and celebration.

“At his core,” Abdurraqib writes, “Cornelius was a journalist who was driven to journalism by a desire to cover the civil rights movement, with an understanding that the movement was inextricably linked to the music that soundtracked it.” By the 1990s, the music and dance became a form of cultural history.

“In that era,” Abdurraqib adds, “the live show was just fine. But the real gems were in the reruns, which would sometimes come on during the day on Sundays… The reruns showed clips from Soul Train’s most golden era, from the mid-‘70s through the late ‘80s, when the weekly musical guests came from the greatest eras of Black soul, funk, R&B, and pop, and the outfits of the audience-turned-dancers were adorned with fringe and frill and gold, their skin dark but for the glitter or jewels along their cheekbones and eyes.”

On the big screen, Abdurraqib saw Black characters presented like never before, although the cultural critic didn’t quite see what most white folks saw. By the turn of the century, the racial strife that defined much of American history was acknowledged within many motion pictures and the perpetrators and their victims were often portrayed with some sense of correcting the record. Unfortunately, as Abdurraqib laments, this reckoning with our past almost always fell short by proclaiming, often subtly, that “This is not who or what America is….. America is better than all of it, we’re all told.” Just as white people can know that donning “blackface” is wrong without knowing why, so too can we be fooled into thinking that just because the black and white guys get along at the end, doesn’t mean the whole history has been told.

This made me remember playing a few scenes from Remember the Titans—the story of a football team at a newly integrated high school—to my eighth grade kids with the presumed message that, sure, yeah we have segregation and all, but if we can just get together and get to know one another, all will be well. Abdurraqib has a different take, which has me rethinking mine. “And [just] like that,” Abdurraqib writes, “the n[*****]s aren’t so bad to play football with after all.”

I saw Remember the Titans as a message of hope while Abdurraqib now suggests that it was just another example of “how movies have been made so relentless in their quest to sanitize race relations in America.”

Turning the whole idea on its head, Abdurraqib reflects on a scene from the movie 8 Mile where the white rapper beats down the Black rapper. It’s the white trash dude in this case who had the beat-down life in Detroit, while the Black brother rapping against him is a product of private schools and a stable middle class family. Who’s the poser now? Who’s the cultural appropriator in this one?*

Even a more recent, supposedly enlightened movie, The Green Book, suffers from the trope found in decades of American movies: the Black guy getting grief from the racists and then the white savior jumps in to save the day. The message for a white audience is comforting: we’re not all racists, right? But what do Black people get out of this?

These are the type of questions Hanif Abdurraqib asks throughout A Little Devil in America; questions we should all be asking ourselves.

*This is the Final Rap Battle scene from 8 Mile. For those not versed in the genre, subtitles help. You should know too that this one has a great deal of profanity.