“And still of a winter’s night, they say,

when the wind is in the trees,

When the moon is a ghostly galleon

tossed upon cloudy seas,

When the road is a ribbon of moonlight

over the purple moor,

A highwayman comes riding—

Riding—riding—

A highwayman comes riding,

up to the old inn-door.

—Alfred Noyes, “The Highwayman”

I was one of the children who grew up hearing about our own highwaymen. Desperados who rustled cattle in the Santa Monica Mountains or hid there after robbing stagecoaches; bandits who buried treasure in sea caves and hid it in secret places in the canyons and never returned for it. The man responsible for most of those legends was California’s own favorite legendary highwayman, Tiburcio Vasquez, who is said to have buried gold in Topanga Canyon.

When the coast route through Malibu opened to the public in 1928, newspaper accounts spoke of “Eerie tales of smugglers, pirates and bad men.” In the early years of the twentieth century there were stories of mountain men paying for their goods in town with Spanish gold or raw gold nuggets. Treasure hunters made headlines seeking gold said to be buried by Vasquez. They would surely find it along the beach between Malibu and Santa Monica, or hidden in a Topanga cave, or buried beneath a Calabasas oak tree, or buried deep among the distinctive stones of the Santa Susana Pass. They hunted, and dug, and theorized, and sometimes even lost their lives in the process, but no treasure was ever found.

When Las Tunas Road was paved in 1915, the Los Angeles Evening Express headline read: “Trail Used by Bandit Will Be Obliterated By Las Tunas Road.” The news item states that, “according to a well defined legend of [Topanga] canyon, Vasquez, a horse thief who is claimed to have made the juncture of Topanga and Garapatos canyons his headquarters, at one time used the trail going through the Trejila [sic] ranch into Las Tunas for cattle rustling.

Vasquez wouldn’t have appreciated being described as a horse thief. He regarded himself as a gentleman highwayman, like the character in Alfred Noyes’ poem—a sort of Californio Robin Hood, who stole from the invading Americans. His crimes did include stealing horses—and cattle—but he also held up stagecoaches, and ransacked stores. On one occasion, he and his gang ransacked an entire town. Vasquez had a reputation for not shooting, provided his victims cooperated—he would leave them face-down in the dust with their hands bound behind them. He went to his death maintaining that he never actually killed anyone himself, but he did shoot a man, and he committed so many other crimes that a jury had no qualms about sentencing him to death.

Educated, urbane, and handsome, Vasquez was well read, played the guitar, wrote poetry, and charmed the ladies. He was regarded by many as an aristocratic man of the people committed to ridding California of American rule, and he never had a shortage of allies and friends who provided him with refuge when he was on the run. Vasquez was so popular that when he was apprehended, he was able to pay for his defense by selling signed pictures of himself to his fans. Vasquez is said to have been one of the main inspirations for the fictional character Zorro, who was created in 1919 by American writer Johnston McCulley, and who keeps the spirit of Vasquez alive even today.

This legendary highwayman pops up in the folklore of many California towns. If even a small percentage of all the treasure he is said to have hidden was real, he would have been a very wealthy man—and a busy one. Syl MacDowell, author of a 1925 Los Angeles Times feature on treasure hunters, quipped that the peripatetic bandit is connected to so many tales of robberies and buried treasure in so many places that he would have certainly worked himself to death if he hadn’t been caught and hanged.

MacDowell places Vasquez’s local treasure cache in Calabasas, where he claims Vasquez would lie in wait for the stagecoach from a vantage point atop a sandstone outcropping—never mind that the Calabasas stagecoach only ran once a week at best, and rarely transported anything more exotic than dusty travelers who couldn’t afford to travel by steamship and the weekly mail. He goes on to attribute the alleged Topanga hoard to a California visit from Billy the Kid, adding that it is “not improbable that the ancient joke smiths of the neighborhood tell this one in the hopes of watching excited diggers and chortling into their beards.”

While no hoard of gold has never been found here, tradition firmly links Vasquez to Topanga in the 1870s, despite discrepancies in the historical record.

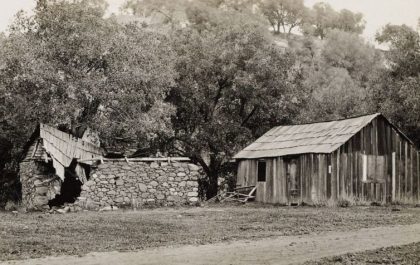

The Topanga Historical Society publication The Topanga Story recounts the legend, which begins with Jesus Santa Maria, the first person to claim a homestead in Topanga. When Santa Maria began carving a homestead out of the wilderness he discovered that the famous highwayman was a neighbor.

“Unbeknownst to Santa Maria, the bandit Vasquez had preceded him. Not wanting settlers in the canyon, Vasquez challenged Santa Maria’s plan for a homestead, but when he found that it was the former mail rider, he backed down saying, “You stay in your end of the canyon and I’ll stay in mine.”

The Topanga Story adds that “Santa Maria related that their paths did cross one more time when Vasquez rode through the ranch fleeing a posse, grabbed a fresh horse and threw some gold on the ground in payment.”

It’s a good story, but there are problems with it. Santa Maria was born in Sonora, Mexico in 1849. According to family records, his family immigrated to California in 1863, when he was 14. Two years later, at the age of 16, Jesus signed on as a Pony Express rider, and worked the mail run in either Bakersfield or San Diego or possibly both until 1868. Several accounts state that Santa Maria staked his claim in Topanga in 1875, but his next appearance in official historical records is his marriage to Elena Maria Valenzuela at the Old Plaza Church in Los Angeles in 1877.

The 1880 census lists Los Angeles as the Santa Maria family’s residence. The couple’s oldest son, Joseph Rosalia Santa Maria, was born in Topanga in September 1881, which suggests that Jesus and Elena moved to Topanga in late 1880 or early 1881. The date inscribed on the old gate at the Santa Maria homestead was 1876, and it is not a stretch to imagine that Jesus did arrive in Topanga in 1875 to stake his claim, waiting until 1880, when he received the deed for the land, to move his family there. However, Vasquez was arrested for the last time on May 14, 1874, and convicted and hanged on March 19, 1875.

The author of the Topanga Story suggests that the incidents involving Santa Maria and Vasquez could have happened earlier, when Jesus first scouted his claim, but Vasquez’ presence in Topanga, like the presence of his legendary treasure, is unlikely, despite the legend being firmly entrenched in local lore.

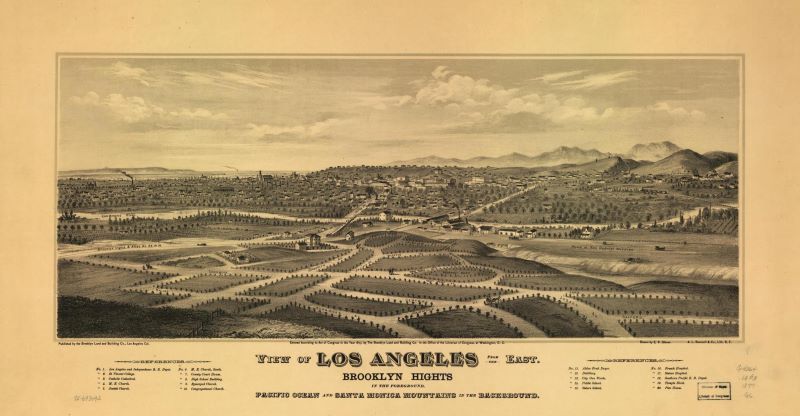

Vasquez was born in 1835, grew up in Monterey, and spent almost all of his life in Central and Northern California, where he committed most of his crimes, beginning at the age of around 17 or 18. Those crimes provide a helpful timeline for much of his life. He spent nine years in prison and was just 39 at the time of his death. Vasquez was briefly active in the Santa Clarita and Antelope valleys—Vasquez Rocks still bears the famous highwayman’s name—but research shows he only spent a few months in Los Angeles County in the period from 1873-74. Vasquez was apprehended for the last time at a ranch in what is now West Hollywood, after briefly evading capture in the San Gabriel Mountains. There is no evidence that he ever ventured into the Santa Monica Mountains. He would have had no motivation to do so. There was nothing of value to steal there, and no allies to provide resources for him.

John Boessenecker is the author of the definitive book on Vasquez, Bandito: The Life and Times of Tiburcio Vasquez, published in 2010. He has this to say about all of the legends of local stagecoach robberies and buried loot:

“[Vasquez] had never stolen chests of gold, and certainly would not have buried the loot. He would have spent it.”

Boessenecker goes on to dismiss Vasquez’ numerous cameo appearances, like his encounter with Jesus Santa Maria in Topanga.

“Tales of hidden treasure represent only a small part of the Vasquez legends. Many claimed they had known him, seen him, or been robbed by him. Anything done by a Spanish-speaking bandit in California was later attributed to either Joaquin Murrieta or Tiburcio Vasquez.”

That doesn’t mean Jesus Santa Maria didn’t encounter horse thieves and cattle rustlers—there were probably plenty of them, but whoever they were, they weren’t Tiburcio Vasquez.

Vasquez remains a legend in Topanga, regardless of whether he ever set foot here, but whether he was a later day Robin Hood or a common thief, he died at the end of a hangman’s rope. In contrast, Jesus Santa Maria was a good husband, father, and neighbor. A kind and generous man who lived to be 94, and died peacefully in his own bed in the home of his son. He is still remembered with respect and affection by his descendants. And yet, it is the ghost of the highwayman we listen for in the moonlight, his golden treasure tempts us, even when it is only fool’s gold.