“It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there’s no knowing where you might be swept off to.”

—J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring

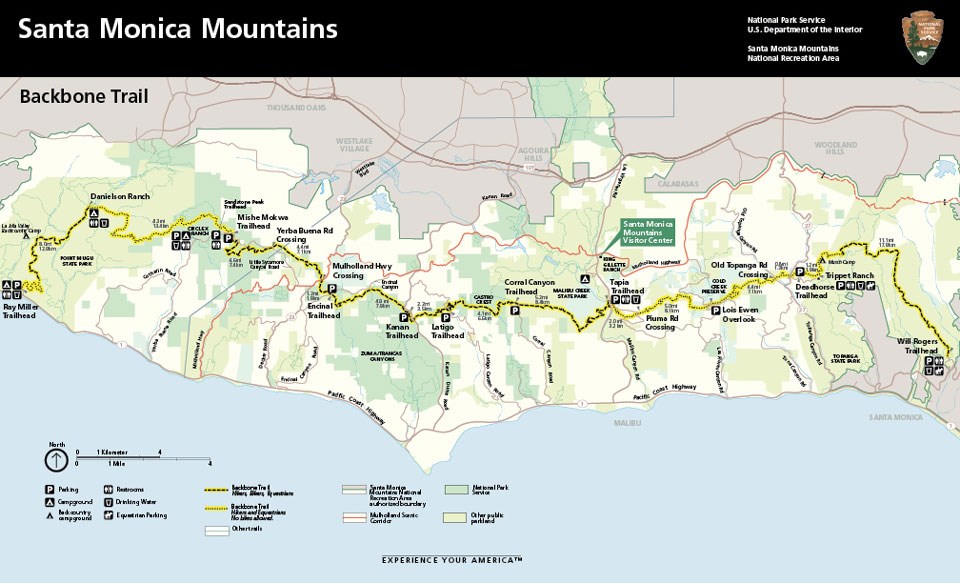

Anyone who has ever taken a hike in the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area backcountry has a good chance of having traveled part of the Backbone Trail, possibly without realizing it. The Backbone Trail winds along the spine of the Santa Monica Mountains for nearly 70 miles, from Point Mugu in Ventura County to Will Rogers State Park in Pacific Palisades. This is a path that even in the dull, prosaic 21st century has the potential to lead to adventure.

The Backbone Trail was first proposed more than 50 years ago, but it only began to become a reality in the 1980s, when the National Park Service, California State Parks, and the newly formed Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy began piecing together the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area.

The trail has a history as convoluted as any of the parkland it crosses. The concept was approved by the California legislature in 1974, four years before the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area was created by an Act of Congress.

By 1983, there were ten miles of trail. By 1990, 43 miles of the route had been constructed, and then the project stalled. The last two parcels were finally acquired in 2016, but just two years after the trail was finally complete, sections were badly damaged in 2018 during the Woolsey Fire.

The damaged areas have been rebuilt and the trail is finally complete and fully open.

Most of the trails throughout the National Recreation Area, including much of the Backbone Trail, were built and are maintained by volunteers. Almost all of the work is done by hand.

“Like the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, the Backbone Trail system has progressed little by little across a patchwork of public lands,” an NPS history of the trail states. “It has been constructed by volunteers, the California Conservation Corps, and professional staff from various parkland agencies. Parts of the trail were old animal paths that became single-track trails; other stretches were converted from fire roads. Only the newer sections have been built to modern trail standards.”

There are sections that originated as wagon tracks made by homesteaders in the late 19th century. Some trails follow ancient Chumash trade routes, and there are also miles of dirt “motorways” once destined to provide access for subdivisions. In a couple of cases the trail follows routes intended for major roads and even freeways.

All off those sections have been connected together by backbreaking labor provided by trailbuilders, who sometimes blazed trails through places no one had set foot since the Chumash and Tongva people were driven from the land, or at least since the last of the Basque shepherds and their sheep vanished from the hills.

Ron Webster was one of the trail builders. He died in 2021, but he left a lasting legacy: 31 miles of the Backbone Trail, beginning with Dead Horse Trail in Topanga Creek State Park. Ron became the leader of a volunteer trail crew for the Sierra Club’s Santa Monica Mountains Task Force. He spent more than 40 years working on trails. He used to joke that people walked all over his best work.

Don Wallace was another key trail builder and advocate. He and his wife Jeanne were part of the original group of equestrians that founded the Trails Council in 1969. Don was a retired firefighter, and on any weekend you might him out on the trails, building and repairing, a new generation of trail builders working with him.

Don lived near Cold Creek Preserve, in the heart of the Santa Monica Mountains, and knew all of the secrets of the area, from Chumash rock shelters and grinding stones, to the names of the homesteaders whose cabins have been reduced to a scattering of stones. He even found a grapevine that was planted at a homestead around 1900, grown from rootstock imported from Spain to the San Gabriel Mission circa 1567 and still thriving, green leaves sprouting from gnarled roots. Don was active on his beloved trails until shortly before his death in 2019.

Milt McAuley was another early proponent for the Backbone Trail. Like Don, he was a founding member of the Trails Council, and he helped to plan and build the Backbone Trail.

Milt wrote the first field guides and trail guides for the Santa Monica Mountains and he and his wife and partner in adventure Maxine used to deliver them in person to sporting goods stores and bookshops all over Los Angeles County.

Milt had an encyclopedic knowledge of native plants and knew where to find the rarest and most unusual. He drew hundreds of ink drawings to illustrate his wildflower field guide, and he knew which plants were edible or medicinal. His books remain essential resources. Milt’s knowledge of trail craft was worthy of a character in a Jack London novel. Before there were trails, he led hikes in the Santa Monica Mountains that involved scrambling through brush and over boulders. Not everyone supported the idea of a trail network, but Milt championed the project.

“If you didn’t build a trail and invite people in, someone would come along and subdivide the land,” he said in a 2001 interview in the Los Angeles Times. “To preserve parkland, you need access to it. Otherwise, nobody will vote the funds to acquire it.”

Milt died in 2008. In 2015 he received a special honor for his conservation work and advocacy. The U.S. Board on Geographic Names/Domestic Names Committee voted to name a mountain peak in Malibu Creek State Park in his honor

Today, hikers can travel from Will Rogers State Historic Park in Los Angeles to Point Mugu State Park in Ventura County on public lands, without encountering private property gaps. Many sections of the trail are also open to mountain bikers and equestrians.

Some stretches of the Backbone Trail are grueling and require a full day, others are short. Most have some serious elevation loss or gain, but a few are surprisingly gentle. This is a constantly shifting landscape. Trails that offered shade and the cover of mature chaparral and oaks have been laid bare by the Woolsey Fire. Volunteers and park agencies work to ensure the route remains passable, but winter storms can erase sections of trail, and downed trees, boulders and landslides are all possible. It’s good to have a plan B.

The shortest segment of the backbone trail is Henry Ridge in Topanga—just a third of a mile from Old Canyon to Topanga Canyon Blvd., or a little less than one mile if one crosses the boulevard and keeps going to the Topanga State Park trailhead off Entrada, and the short stretch from Encinal Canyon Road to Decker Canyon is just 1.1 miles.

The segment from Will Rogers State Park trailhead on Sunset Blvd. to “the Hub,” —a place where several trails meet in Topanga State Park—is a serious hike of nearly 11 miles with considerable elevation gain. The longest leg of the journey is near the far western end of the trail: the hike from Triunfo Pass to Big Sycamore Canyon in Point Mugu State Park is 13.46 miles one way. Many hikers prefer to sample a smaller section of this segment, like the dramatic four-mile out-and-back hike up 3111-foot-high Sandstone Peak, the highest mountain in the range.

Walking the entire Backbone Trail is a badge of honor in the local hiking community, but the only practical way to tackle the trail is in segments. There are plans for adding campsites to enable dedicated hikers to through-hike the route, but they aren’t in place yet and have faced pushback from residents concerned about the fire risk.

Those of us with a love of the mountains but no particular ambition to walk the entire trail tend to have our favorite sections, often the ones nearest home. Traveling a little farther afield can offer new adventures and new perspectives on the National Park in our backyard.

There are amazing things along the way: views of the Channel Islands like the Blessed Isles in a fairy tale; fog at one’s feet, and the peaks like floating islands; and hidden ravines with waterfalls in the winter, and the vivid colors of spring flowers or autumn leaves.

Winter and spring, when the weather is cooler and the landscape is greener, are the most beautiful and least crowded time of year to hike in the Santa Monica Mountains, although one can always find solitude, even on a summer weekend, if one opts for a less traveled corner of the park.

Information on the Backbone Trail, including maps, advice and a series of GPS coordinates to help hikers navigate the complex network of trails, is available at nps.gov/samo/planyourvisit/backbonetrail. For a virtual tour of the trail, check out https://www.facebook.com/watch/80124818659/810346979562251