This article was originally published April 21, 2023 in Topanga New Times. TNT’s features “The Train to Nowhere: Travels on the Hueneme, Malibu & Port Los Angeles Railway,” and “On the Track of Malibu’s Ghost Train,” are two of our most popular stories. This article provides the background for those stories, and was presented as part of our first ever live Salon Series Tea @ TNT event on April 2.

From the moment the first transcontinental railroad steamed across the county in 1869, the nation had train mania. In California, that mania reached a fevered pitch once transcontinental rail travel was a reality. The railroad had an unimaginable impact on the West. It opened vast swaths of the United States to development and commerce. It was the mighty tool of 19th century American colonialism, irrevocably carving up a vast land that had been home to hundreds of Native American nations, and would soon be farmland and new towns. A big part of that push was driven by the need to reach California—and the riches it represented.

The Golden Stake Ceremony at Promontory Point, Utah, on May 10, 1869, celebrated the moment when Central Pacific Railroad’s Sacramento Line connected for the first time with the Union Pacific Railroad line from Omaha, Nebraska. The famous photo taken by Andrew J. Russell, to commemorate the event, preserves an extraordinary moment of time, a moment when the world changed. Russell, a Civil War photographer who came west after the war to chronicle the rails, was aware that he had captured a key moment in history with his glass plate image of the celebration at Promontory Point.

“The continental iron band now permanently unites the distant portions of the Republic, and opens up to Commerce, Navigation and Enterprise the vast unpeopled plains and lofty mountain ranges that now divide the East from the West,” he wrote. What the Native American people displaced by the railroad felt about their lands being described as “unpeopled,” no one apparently bothered to ask. The government granted huge swaths of their land to the railroads, and the railroads facilitated rapid growth.

There aren’t any women in Russell’s photo, but in 1905, on a remote stretch of the California coast, the railroad was going to run headfirst into one particularly stubborn and determined woman. That was unimaginable in 1869. The railroad was unstoppable.

The transcontinental railroad delivered almost everything promised. It transported goods and produce, mail and news, and people, hundreds of thousands of people, in record time, time that also changed to accommodate this new, steam-powered world. The railroads were responsible for the first standard time system in North America in 1883. For trains to run on time, time had to be standardized.

The railroad touched off a new California gold rush, for land this time instead of actual gold. It also helped to create California’s tourist culture. Glamorous ads added a romantic cachet to the California coast. In 1898, Southern Pacific launched Sunset magazine to help promote that newly created travel opportunity. Railroad routes were being built everywhere, and one of the major goals was to build a coast route from Los Angeles to San Francisco. It would be spectacular, with the ocean on one side and the coast ranges on the other, a rail route like no other. An army of workers was dispatched to build the coast line. The railroad arrived in Ventura in 1887, and reached Port Hueneme in 1905, but that was the end of the line.

In Los Angeles, a railroad building frenzy was also underway. The first railroad was built in 1868. It ran from San Pedro to Los Angeles to bring goods and supplies into the rapidly growing town. Los Angeles did not have a natural harbor, but San Pedro was the closest thing to one and was already in use as a port when the US annexed California from Mexico. This rail line was planned by Phineas Banning, the man responsible for the modern port at San Pedro. Banning knew a lot about ships and the coast and had his pick of locations, and he didn’t choose to build a port in the remote and wild Santa Monica Bay.

That didn’t stop a pair of ambitious real estate speculators from planning one. In 1872, a sizable chunk of the old Rancho San Vicente and Boca de Santa Monica ranchos—38,409 acres—was acquired by a man who styled himself Colonel Robert Symington Baker. No one seems entirely certain what he was a colonel of, but there doesn’t seem to be much evidence it was the US Army. However, Baker came to California during the gold rush and made a fortune selling supplies to the miners. He gained a much bigger fortune when he married Arcadia Bandini de Stearns in 1875. She was an heir to the Bandini family fortune and the widow of the fabulously wealthy Abel Stearns.

In 1874, Baker sold a half interest in the Santa Monica property to another colorful character, Nevada Senator John P. Jones. Jones made his fortune in silver at the Comstock lode, before going on to become a US Senator.

In an effort to make the Santa Monica land more desirable, Jones built the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad, laying 16 miles of track, from a hastily cobbled together wharf on the edge of the Santa Monica Bay to Downtown Los Angeles. Baker and Jones pitched the idea that this new railroad would enable the Santa Monica Bay to become the Port of Los Angeles.

The Santa Monica Bay, with its forbidding cliffs and big surf, was not a promising location for a port, but it was a good marketing ploy. Baker and Jones partitioned part of their Santa Monica holdings into lots, and auctioned them off on July 15, 1877, kicking off a land rush in Santa Monica.

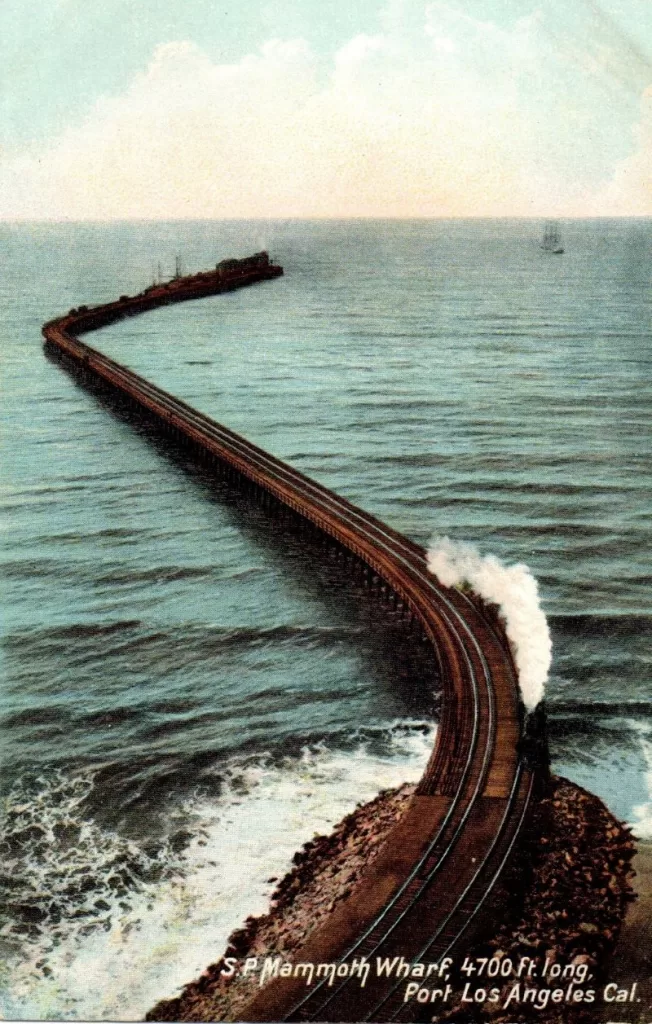

By 1880, Santa Monica was a modestly bustling town, and Jones had sold the railway to Southern Pacific, which took the Port of Los Angeles idea and ran with it. Lumber and labor were cheap, and Southern Pacific had plenty of political influence. Southern Pacific ran a line all the way out to Potrero Canyon, just past Santa Monica Canyon, and built what was billed as “the longest wharf in the world.”

The structure, grandly titled Port Los Angeles, was a mile long and dominated the coast. The train tracks ran all the way out to the end of the pier, where steamships waited with cargoes of passengers and wood from Northern California. This wonder of the railroad era was built in 1892 and opened in 1894. The train route ended just north of the pier, where there was a railroad turntable, but Southern Pacific had plans. The Long Wharf was just the beginning: this new rail would connect Port Los Angeles with Port Hueneme in Ventura.

There was a big problem, a bigger one than the remote and difficult terrain. Southern Pacific didn’t own the right of way, and the year work began on Port Los Angeles/Long Wharf, the old Topanga Malibu Sequit Rancho was sold, and not to the railroad company.

The Malibu Rancho was an original Spanish land grant property originally awarded in 1804 by the Spanish government to a retired soldier. When it was purchased by Frederick Hastings Rindge and his wife, Rhoda May Knight Rindge, in April of 1892, it was still intact—14,000 acres with more than 20 miles of coastline—and it was almost completely undeveloped, uninhabited, and unspoiled.

Frederick inherited a mighty fortune from his father and added to it. He is better known in his native Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he donated the money to build the city hall and library and his name is everywhere. He is mostly forgotten in Los Angeles, although he invested in massive real estate holdings in addition to the Malibu Rancho, founded the Conservative Life Insurance Company (now Pacific Life), became vice-president of the Union Oil Company, and the director of the Los Angeles Edison Electric Company (now Southern California Edison Company).

Frederick’s wife May was capable and smart. She had been a school teacher in rural Michigan when they met. She was good at mathematics, could ride and shoot, and most importantly, think for herself.

Frederick’s plan for the Malibu Rancho was to build a riviera by the sea to rival the European Riviera, but he had a romantic and poetic nature and fell in love with the beauty and solitude of the land. Instead of putting Malibu on the map, the Rindges kept the world out. It was their own private paradise, where the family went on weekends and holidays.

While the Ridges were enjoying the country life on their newly acquired slice of terrestrial paradise, Southern Pacific continued to work on acquiring the right-of-way across the land. The railway executives had no reason to think that they wouldn’t succeed. Southern Pacific was unstoppable.

There was talk. Rumors flew, and it was true that equipment was beginning to move down the road towards the Malibu Rancho, but it wasn’t Southern Pacific. Frederick Rindge had found a loophole: if he built his own railroad, he could keep Southern Pacific out.

Frederick began to quietly buy up land for the proposed railroad route, expanding the rancho to more than 17,000 acres, but before the railroad got off the ground, he died unexpectedly. He was 52.

May was left with her husband’s business and the couple’s thee young children. She wasn’t romantic but she was committed to preserving the Malibu estate for herself and her family. She became one of the first and only female presidents of a railroad company. This was an unheard of thing at a time when women had few rights and couldn’t even vote. May incorporated the railway, issued stock, and began laying track for the Hueneme, Malibu, Port Los Angeles Railway.

The track began near Carbon Beach. It took three years to build 15 miles of rail in extremely difficult terrain. Construction stopped in 1908. May held the right-of-way all the way up to the Ventura county line but construction never resumed, although the legal battle over the right-of-way continued to be fought.

In 1917, May Rindge won a major victory. The California Supreme Court ruled in her favor, giving her the right to keep Southern Pacific out. A news feature on the court decision in the Los Angeles Times provides a rare quote from her about Malibu: “It is our home,” she says. “We plan for it together—my children and I. We manage to spend some time there every week and we take great pleasure in it.”

May’s victory was short-lived. She would spend the next decade fighting to keep the coast highway out, a battle she would lose in the end, but she won this round. May Knight Rindge stood in the way of one of the most unstoppable forces on earth and stopped it. The mighty Southern Pacific Railway had to turn inland at Ventura, instead of following the coast. May Knight Rindge’s victory left an indelible mark on the map.