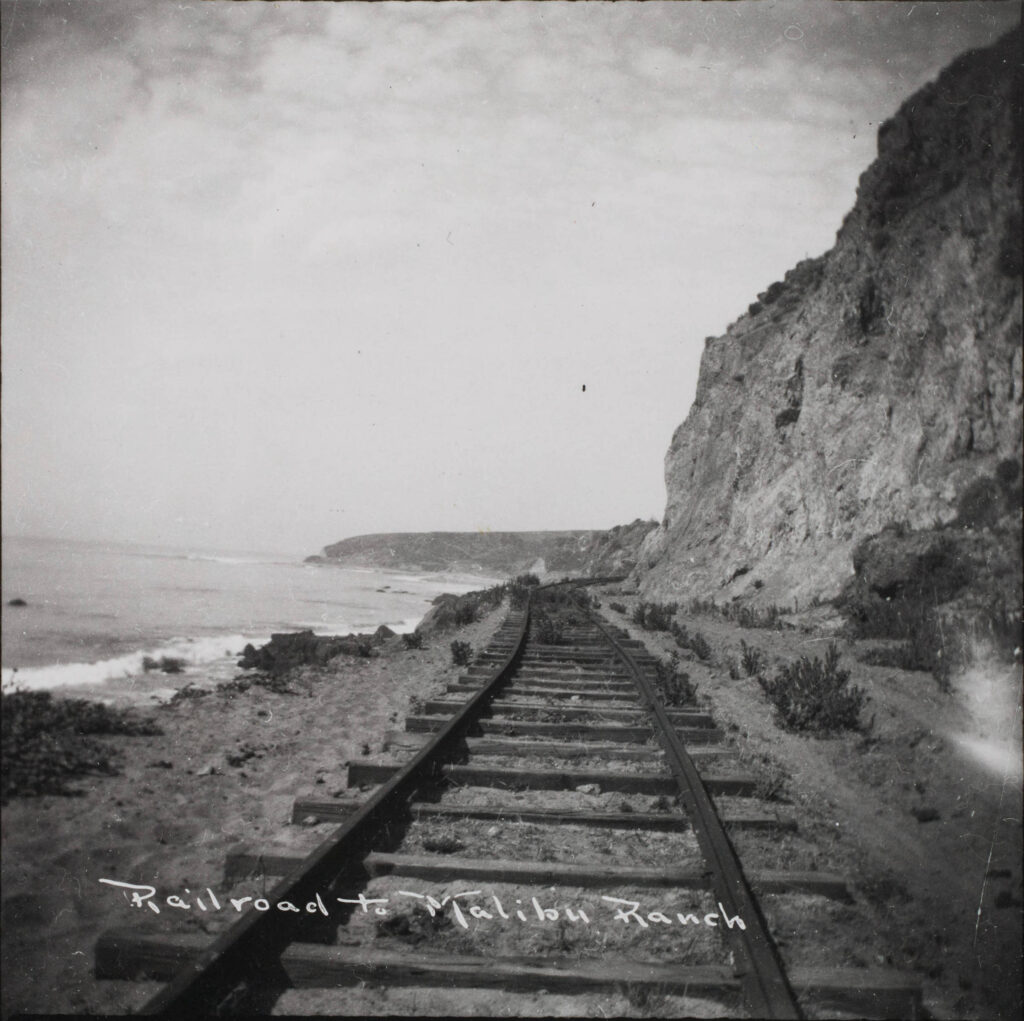

Imagine a train steaming along the beach, just yards from the ocean on tracks laid on the shifting sand. It sounds like a surrealist painting by Magritte, or a scene from a Miyazaki movie, but it was real—or almost real—at least for a little while.

When the Topanga Malibu Sequit Rancho was purchased by Mathew “Don Mateo” Keller in 1857, a railroad across the old Spanish land grant estate seemed inevitable. The first railroad survey map of the Malibu coast dates to 1869. An 1876 announcement in the Los Angeles Herald proclaimed: “A railroad from the new Southern Pacific railroad depot at Los Angeles can be run over a good route to Point Dume or Dumas Cove, which is the best harbor between San Francisco and San Diego.”

Railroads proved more than just transportation. They were a driving force in the development of the west. The railroad companies were given vast tracts of land by the Federal government and were essential in opening up that land. A train route through Malibu would enable development in previously inaccessible parts of the Santa Monica Mountains. Development interests helped fuel the push for a coastal rail route.

Southern Pacific already had plans for a Malibu route when the tracks were laid for Long Wharf at what is now Will Rogers State Beach in Pacific Palisades. This 4,700-foot-long pier was billed as the longest in the world. It was promoted by Southern Pacific Railroad magnate Collis Potter Huntington, and a monument to the boom era of the railroad.

The official name for the Long Wharf was the Port of Los Angeles, although the title was wishful thinking: Los Angeles did not have a natural harbor and the Santa Monica Bay with its open ocean conditions and potential for heavy surf was not ideal for shipping. The Long Wharf was soon eclipsed by the much bigger and more practical port at San Pedro. The wharf was primarily built to bring in lumber and other necessities needed for a rapidly growing Los Angeles. Southern Pacific, the force behind the wharf, ran track all the way up the coast and out to the end of the pier to quickly move cargo into town.

In 1892, the same year construction began on the Long Wharf, Don Mateo’s son Henry Keller sold the 13,000-acre Malibu Rancho property to Frederick Hastings Rindge and his wife Rhoda “May” Knight Rindge. Southern Pacific didn’t know it yet, but the all-powerful company that had successfully rewritten the history of the American West just had one of its last great railroad schemes go up in smoke.

Frederick Rindge was an astute New England businessman who invested the fortune he inherited from his father in practical and profitable things like oil, utilities, and real estate in Los Angeles, but he was also a deeply religious and romantic man with a love of poetry and nature. His development plans for the coastline he acquired from the Keller family were tempered by his love for the beauty of the land.

When Southern Pacific began its push to extend its railway from the Long Wharf to Port Hueneme across the Malibu Rancho, Frederick Rindge pushed back. Jerome Madden, in charge of Southern Pacific’s Land Department, was not pleased. “[We] are anxious to see those lands settled and improved,” he told the Ventura Free Press on January 26, 1900. “It would be far better for us and for everybody else if these disputes had been settled long ago.”

It’s unclear if Frederick Rindge ever intended to build a complete railway route when he incorporated the Hueneme, Malibu, Port Los Angeles Railway in 1903, or if his goal was always to block Southern Pacific, but at some point he discovered a loophole in the law that stated that there could only be one railroad right of way on a property. By building his own railroad, Frederick could keep the other railway out. He began buying out homesteaders at the western end of the ranch to facilitate construction of his own personal railroad. The ranch expanded several miles west to accommodate the proposed private rail route, but just as construction was getting underway in 1905, Frederick died.

May Rindge stepped up to the challenge. She was 41 when her husband died. She was a school teacher in a small sheep ranching town in Michigan before Frederick swept her off her feet and married her after a one-week courtship. She became one of the first women ever to serve as president of a railway company.

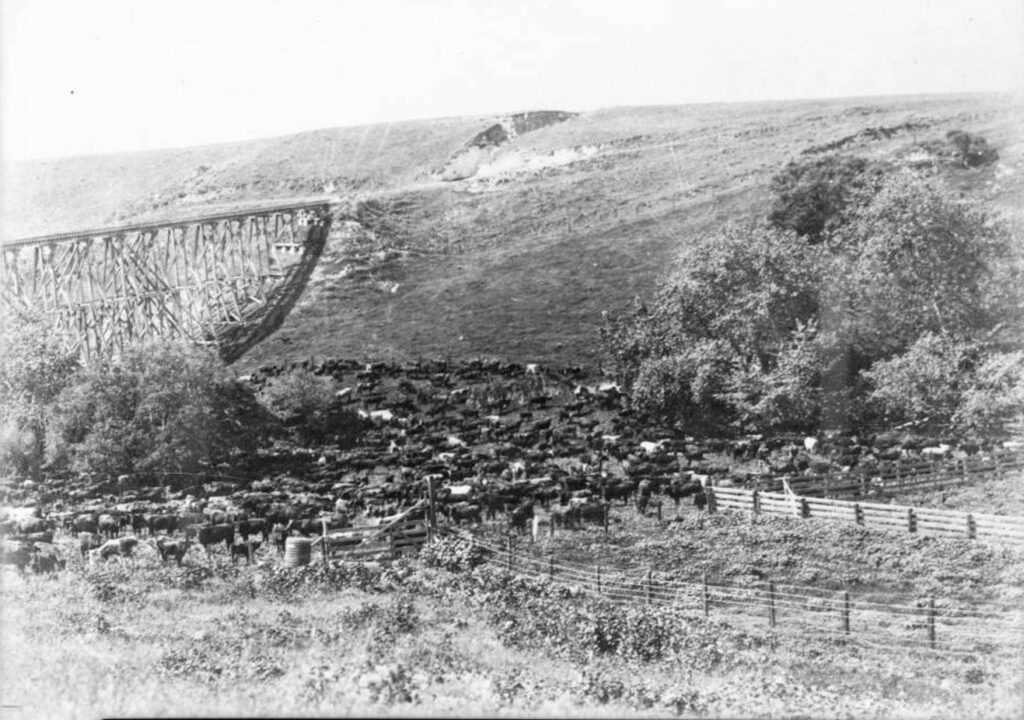

It wasn’t easy. May built 15 miles of standard-gauge track, from Carbon Canyon to Encinal Canyon. It was an engineering feat. The route crossed canyons on precarious trestles and negotiated the narrow strip of sand between the ocean and the sea cliffs. Supplies were brought in by barge and delivered at the newly constructed Malibu Pier.

A January 1906 letter from May to Virgil Bogue, the West Coast vice president of Southern Pacific’s rival railroad Western Pacific, outlines how one of the directors of her railroad, General M.H. Sherman, double-crossed her. She explains that he secretly purchased a right of way needed for the Rindge railroad and then incorporated his own “Santa Monica Railroad Company” with another partner, using almost the identical charter as the Port Los Angeles Railroad. “This I consider a breach of good faith,” she wrote.

The letter is ostensibly an offer to sell the ranch route to Western Pacific, but it reads as an outlet for May’s anger and desperation over what she viewed as a betrayal. If a sale was ever seriously discussed it never came to fruition, but rumors about Western Pacific’s involvement circulated for years. In April of 1906, the Los Angeles Times broke the news that Port Los Angeles Railway had secured the contested right of way through the Marquez Rancho (now Pacific Palisades). The Times theorized that the “mysterious railway activity” in Malibu was the work of railroad tycoon George Jay Gould, the owner of Western Pacific Railroad, and that he was plotting against longtime rival Southern Pacific. The Santa Barbara Weekly Press went one further, describing Gould’s alleged plan as an “inimical” move against Southern Pacific Railroad, and a key link in Gould’s transcontinental chain.

Subsequent features in the local papers disclosed increasingly elaborate plans, the reporting based on rumors “generally conceded to be almost certain by those ‘on the inside.’” They included lavish descriptions of “magnificent” hotels, “high class” resorts, and a two-hour express trip by electric rail to Ventura.

In 1907, The Morning Press reported that the number of ties and nails being used to construct the Malibu railroad was proof positive that May Rindge was building an electric trolley to serve a soon-to-be-built city by the sea. In 1911, The Santa Barbara Weekly Press announced that “town lots” for this imaginary city would soon be sold, and that “this action will be followed quickly by a southerly extension of the railway to the Ventura County line, where connections will complete a new and highly picturesque route of travel from Los Angeles to the northerly portions of the state.”

By 1916, the state railroad commission was tired of delays. It tried an end run around the Rindge family, granting an order permitting “absorption” of the Hueneme, Malibu & Port Los Angeles Railway. “The route will be completed,” the Los Angeles Herald announced with misplaced optimism. It wasn’t.

May Rindge was victorious in her battle against Southern Pacific. She succeeded in building her own railroad and circumventing some of the most powerful industrialists in the county, but the era of the train was already reaching the end of the line, and the automobile would soon be an unstoppable force.

May lost the subsequent battle with Los Angeles County and the State of California over the right of way for Pacific Coast Highway, but not without a fight. She took the battle to protect her land all the way to the Supreme Court in 1923.

The state highway route through Malibu was begun in 1924 and completed in 1929. Up the coast, the Hollister and Bixby ranches successfully diverted the coast route inland, perhaps because their owners were men.

Frederick’s death left May to cope with the ranch estimated by May to be 30,000 acres by 1906, the feud with the railroad, the Rindge real estate holdings in Los Angeles, and the couple’s three children: Samuel, 17; Frederick, 15; and Rhoda,12.

It cost her a significant part of her fortune, but May was able to keep the railroad, the coast highway and the world out of Malibu for nearly two decades. The Depression and WW II extended the moratorium on building for another generation, sparing Malibu and the Santa Monica Mountains the building boom experienced by other coastal communities.

She wasn’t a conservationist, she wasn’t motivated by altruism, and she didn’t have her husband’s passion for nature, but in a real way, May Knight Rindge helped save Malibu and the Santa Monica Mountains from the destiny Southern Pacific and subsequent developers planned. There is a Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area today in large part because of one stubborn, determined woman who refused to yield.

The Hueneme, Malibu & Port Los Angeles Railroad began and ended in the middle of nowhere. It never had a station, a destination, or even a train—just a 15-horsepower, gasoline engine and two flat cars—and the tracks were covered by sand in some areas almost as soon as they were laid, but this train to nowhere served its purpose. Instead of opening Malibu to the world, it kept the world out.

Today, all that is left of the Malibu railroad are a few fragments of track buried under the sand on the beach, but this historic train still offers us a trip into the past, a railway journey into a vanished world.

All aboard.

If you are a history buff, be sure to listen to this wonderful podcast with Suzanne Guldimann

What a terrific article! Thanks.

Thank you, Ernest! May Rindge vs Southern Pacific is the stuff of legends. I had a lot of fun putting this feature together. One of the trestles was near where I grew up and even though there was nothing left, rail spikes used to turn up. I still have one. A link with that glorious story of stubborn determination!

Thanks for a fun and interesting article

Thank you so much, Dennis! That means a lot coming from a local historian like you!

Great article. I learned some things that I had not known before. I am a third generation family member from Malibu. We left Malibu years ago but it still has a place in my heart…

Loved the article

Ventura County Railway is one of my favorite

This is so cool! I never knew any of this! Does a map exist of where all the tracks were laid?