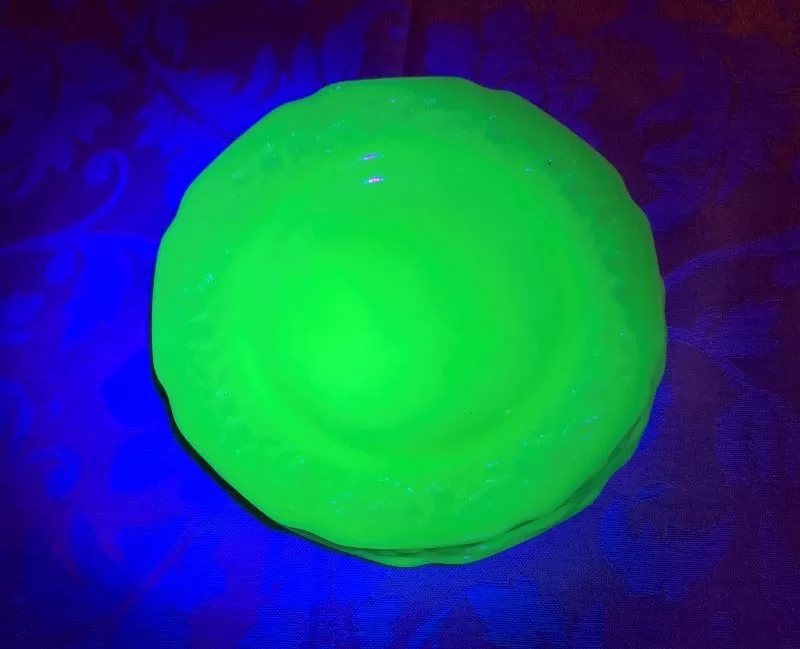

They belonged to my grandmother: six delicate dessert plates made from translucent greenish-yellowish glass with a pattern of apple blossoms embossed around the rim. My mother always called them “milk glass.” They sat in the cupboard for decades, only used on those rare occasions when half a dozen small dessert plates were called for. That’s probably just as well, because those six small dishes contain a substantial amount of uranium.

Uranium glass was all the rage in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Today, it is sometimes called “vaseline glass,” for its translucent quality and distinctive yellowish color, or “Depression glass” because of its popularity during the 1930s, but it was already being mass produced as early as the 1880s in Great Britain, by the Whitefriars Glass Company in London.

Collectors Jay Glickman and Terry Fedosky wrote one of the first comprehensive guides to this type of glass in 1998: Yellow-Green Vaseline! According to the book, Bohemian glassmaker Josef Reidel is often credited with first adding the element to his glassware around 1830 to create uniquely vibrant green and yellow glass. That wasn’t long after the element uranium was identified in 1789, by German chemist Martin Heinrich Klaproth, who named this element after the recently discovered planet Uranus, named from Ouranos, the ancient Greek god of the sky.

Glassmakers already used an assortment of elements to color their wares, including cadmium, cobalt, and manganese—all of which can be toxic if ingested. Uranium offered an exciting new color—an ethereal yellow-green that seemed to almost glow in the right light. It really does glow under UV light. That’s not because uranium is radioactive, but because it is fluorescent.

Uranium glass was used for spectacular one-of-a-kind luxury items produced by Baccarat, and prosaic dimestore tchotchkes like ashtrays and trinket boxes. By the 1930s there were millions of uranium glass plates and dishes, citrus juicers, vases, fish bowls, ashtrays, teapots, marbles, and even rosary beads.

Milky white pieces like my granny’s dessert dishes were an invention of the late nineteenth century, when uranium glass started to be made with the addition of heat-sensitive chemicals that turned the glass opaque. In the US, glass manufacturers continued to use the material for household wares until WWII, when the government appropriated all uranium for use in its effort to create an atomic bomb.

The amount of uranium used to manufacture this type of glass varies greatly. Granny’s dessert plates, manufactured in the mid 1920s, may contain as much as 10 percent uranium by weight. Oak Ridge Associated Colleges Historian D. Ray Smith is the curator for the ORAU Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity in Tennessee. He has helped amass and research a formidable collection of radioactive housewares, quack cures, and other materials. According to the Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity website, the amount of uranium present in this type of glass ranges from around two percent to a whoping 25 percent by weight. All of it emits radiation, but the levels are considered safe. A report published by the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission in 2001 found that uranium glass is considered to be safer than many kinds of household electronics.

As scary as uranium sounds, most of the radiation emitted by this type of radioactive material is produced by beta particles, which can be blocked by ordinary materials like glass, wood, human skin, and even paper. Uranium glass stored behind the doors of a china cabinet is not a major health hazard. Using a uranium glass citrus juicer, or drinking the resulting orange juice out of a uranium glass tumbler every morning is not advised, but it still wouldn’t expose the user to an excessive amount of radiation. The most serious risk occurs if a uranium glass object is chipped, cracked, scratched, or broken, generating small fragments that could be ingested or inhaled.

Uranium finds its way into another family of common household items: ceramics and glazed pottery. The most popular kind of early Fiestaware—the glorious orange-red color first produced in 1936—is the best known example of radioactive dinnerware, but many manufacturers of ceramics used uranium oxide to produce cream, yellow, pink, orange and red shades.

Smith notes on the ORAU website that, “It is worth noting that the use of uranium to produce a red ceramic glaze was not limited to Fiestaware. Almost any antique ceramic with a deep orange/red color is likely to be radioactive.”

There’s also a good chance that the pretty yellow, orange, green, red, or cream tiles on the walls of a 1920s bathroom or kitchen contain uranium.

Uranium has been used in the manufacture of ceramic tile going all the way back to ancient Rome, but one of the reasons it became popular at the turn of the last century is connected to Los Angeles. The heavily embroidered romance of Old Spanish California was at its peak popularity in the 1920s, and the passion for Spanish colonial revival fantasy architecture included tiles and housewares in the same theme.

Many companies using uranium oxide were right here in California, including Matlox, whose Poppytrail dinnerware remains a desirable collectable, and Franciscanware, which produced a line of beautiful uranium glass “Madeira glasses” to add a Spanish-themed romantic touch to the dinner table.

The spectacular art tiles created by the Malibu Potteries in the Spanish-Moorish style are full of uranium oxide. Every brilliant red or orange accent contains enough to set a Geiger counter ticking, but that doesn’t mean that it is hazardous to human health.

Uranium isn’t the only cause for concern. Lead is also present in most dinnerware from this period. It’s not radioactive, and neither is cadmium—another element frequently used in glass and pottery—but they have the potential to be highly toxic. There are few controls on decorative pottery and dishes made for pets—they can contain extremely high levels of lead, and so can a surprisingly wide assortment of imported pottery and ceramics, including dinnerware. It’s a good idea to never use any vintage dinnerware or glassware that is cracked, pitted, scratched or chipped.

Uranium was used in these products not because it was radioactive, but because it created beautiful colors and effects. Some companies still produce uranium glass as a novelty—made after WWII with depleted uranium—but it is no longer produced for use in the kitchen or on the dining room table.

The government classes the uranium present in these types of radioactive products as NORMs—naturally occurring radioactive material. They aren’t considered hazardous waste, there are no controls on buying, selling or disposing of them, and they remain popular with collectors because of their beauty and weird history.

Products that intentionally contain radioactive material used specifically for its radioactive properties include radium watch dials and instrument panels (used for the element’s glow-in-the-dark property), smoke detectors (a small amount of americium-241 is still used in ionizing smoke detectors), and even incandescent gas camping lantern mantels (thorium was widely used because it glows brightly when heated—it has now been replaced with non radioactive yttrium).

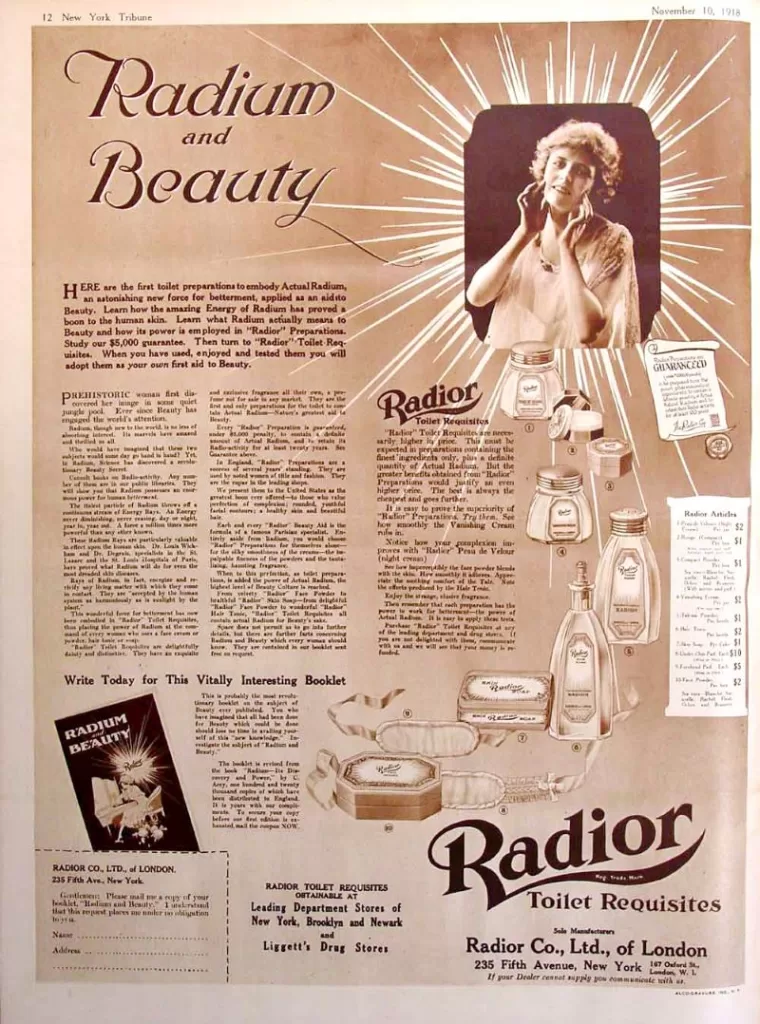

In the first decades of the twentieth century there was a more sinister assortment of radioactive products created to cater to the craze for radium after Marie Curie discovered the element in 1898.

Radium was hot—literally and figuratively. Ladies wore “radium silk” a fabric that mercifully did not actually contain radium, and powdered their faces with radium powder, which unfortunately did. Couples danced the Radium, thrilled to the Great Radium Mystery, a silent era thriller serial starring platinum blonde Cleo Madison, and they refreshed themselves with “health-giving” radium water.

Many products like “X-Radium Heaters” were pure quackery, and completely harmless. Others purported to contain radium, but actually contained uranium ore—radium was far rarer and a lot more hazardous to human health. The Radior line of “miracle” face cream and powder really did contain radium and thorium.

Radithor, a patent medicine manufactured from 1918 to 1928 in New Jersey also contained genuine radium. Eben Byers was a celebrity spokesperson for this product—a socialite who could be described as one of the first “social influencers.” He drank so much Radithor that his bones dissolved. He was buried in a lead coffin to prevent his remains from spreading radioactive contamination into the environment after his death in 1932 from multiple forms of aggressive cancer. The photographs are too gruesome to share here.

Byers death led to changes to the Food and Drug Administration’s powders and resulted in the banning of radioactive ingredients in patent medicines, but that doesn’t mean radioactive quackery isn’t still a thriving business. In 2021, officials in the Netherlands banned the sale of jewelry that purported to generate negative ions and shield the wearer from electromagnetic field radiation from G5 cell towers. Ironically, the items contained radioactive materials that emit unsafe levels of gamma radiation.

Radioactive waste is everywhere: fallout from above-ground nuclear weapon tests, radioactive waste from coal and oil production, contaminants like thorium-nickel-alloy airplane parts, thorium from vacuum tubes, tritium from thermostats, and radium instrument panels. However, naturally occurring radiation is also everywhere. There are beaches in Southern California with concentrations of radioactive thorium. The earth is constantly bombarded by cosmic radiation, and even the humble banana can contain radioactive isotopes of potassium. Radioactivity is part of life, scary or not.

Uranium glass is a curiosity from the dawn of the nuclear era. Those six small dessert plates are a reminder for me of my much-loved grandmother who was born the same year Madam Curie discovered radium. The half life of the uranium in the average piece of uranium glass or ceramics can be as much as 4.5 billion years. It will be here long after my granny’s set of dessert plates and all of the people who will ever own them are long gone. It makes one wonder what we are using now that someone will be writing a cautionary feature about a hundred years from now.