In Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause, historian Ty Seidule knocks Confederate General Robert E. Lee off his high horse. Seidule is a retired US Army Brigadier General and current Professor Emeritus of History at West Point. He presents compelling evidence that Lee was an unrepentant slaver, a violent defender of white supremacy, and a traitor to the United States, dispelling the glamour and heroism that have inflated the Lee narrative for well over a century.

Most remarkable about this revealing book is that its author was a child of the South. He attended Washington and Lee University in Virginia, and served in an institution that venerated Lee—the US Army. Seidule was taught, and actively embraced the gospel that the South of the 1860s had engaged in a just war in defense of states’ rights and that slavery was morally consistent with the natural supremacy of the white race. “Both sides [in the Civil War] were equal” Seidule reflects upon what he was taught, “except everyone I knew saw the Confederates as more romantic, the underdogs, the heroes.”

Turning on its head the notion that history is written by the victors, Seidule writes that “[t]he Lost Cause became a movement, an ideology, a myth, even a civil religion that would unite first the white South and eventually the nation around the meaning of the Civil War.”

None of us is immune to the power of myth. During my early days in the classroom, I portrayed Lee as he was portrayed in our history text; as a dignified soldier and better general—defeated only due to the overwhelming industrial superiority of the North. I added that Lee was a loyal defender of his home state of Virginia and fought valiantly with limited resources and then surrendered graciously after accepting the inevitability of defeat. Unfortunately, none of that is true.

Redefining the meaning of the Civil War served an urgent purpose for the South; managing nearly four million former slaves. By re-casting the war as a noble struggle against “Northern Aggression” and a constitutionally sound defense of the rights of states, the myth ignored the widely documented founding principles of the Confederacy – the natural superiority of the white race and the maintenance and propagation of slavery.

“My former hero, Robert E. Lee,” Seidule laments, “committed treason to preserve slavery. After the Civil War, former Confederates, their children and their grandchildren created a series of myths and lies to hide that essential truth and sustain a racial hierarchy dedicated to white political power reinforced by violence.”

“As it turns out, the lies of the Lost Cause infused every aspect of my life,” Seidule screams off the page, “and that pisses me off.”

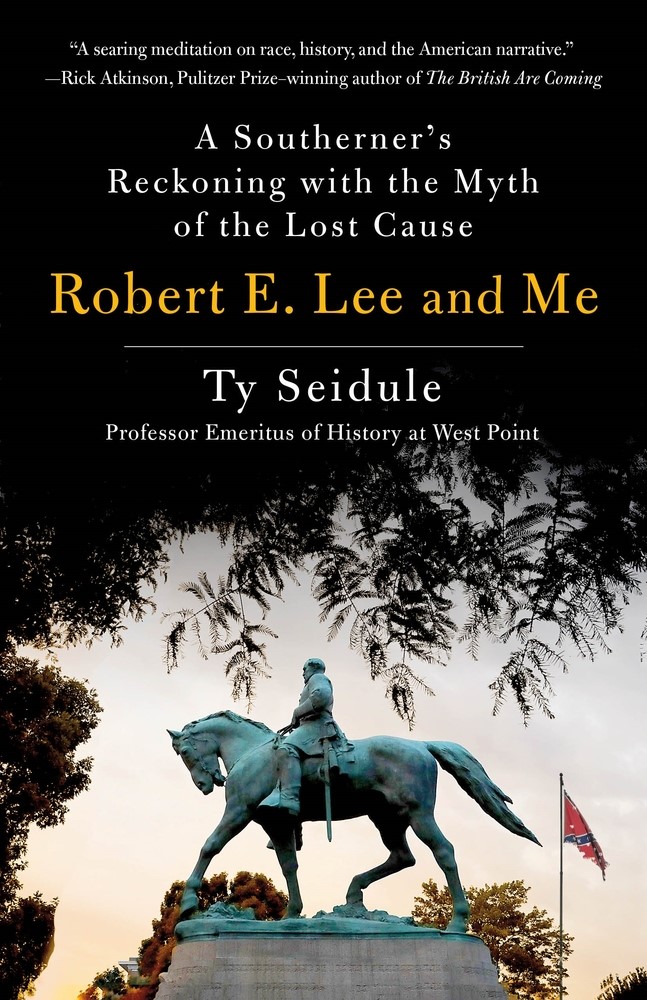

As we wrestle today with the vestiges of the Lost Cause in the form of statues and other memorials to the Confederacy, Seidule asks us to consider who built them and why. “A monument,” Seidule notes, “tells historians more about who emplaced it than it does the figure memorialized.” In this case, the vast majority of nearly 800 monuments to the Confederacy were erected from the 1890s to the 1950s; directly paralleling the era of Jim Crow. Honoring the Confederacy became a tool of subjugation as these monument builders actively perpetuated the “flawed memory of the Civil War,” Seidule proclaims, “a lie that formed the ideological foundation for white supremacy and Jim Crow laws, which used violent terror and de jure segregation to enforce racial control.”

Today, supporters of the Lost Cause aggressively defend the public display of Confederate memorials as racially benign symbols of an honorable and just fight. Other, more rational Americans, see their efforts as a wicked affront to the harsh realities of American slavery and its offspring: Jim Crow, the War on Drugs, Mass Incarceration, and the modern social and economic inequalities that continue to be fed by all that hate.

Despite the current white nationalist backlash, many of the statues are coming down. Street, park, and school names are being changed. In many cases, the new names honor those whose stories had been subsumed by the Lost Cause myth.*

This is the power of history; to rethink why we were taught the things we were taught and, in my case, how I ended up perpetuating a myth of epic proportion and consequence.

However, challenging passionately held beliefs in the modern world with evidence and facts—with history—has become a blood sport. “History is dangerous,” Seidule writes. “It forms our identity, our shared story. If someone challenges a sacred myth, the reaction can be ferocious.” Indeed, upon publication of a 2015 video lecture castigating instead of celebrating Lee, Seidule was inundated with hate mail and death threats, which continue to this day.

Inspired by former President Trump’s nods to white nationalism, that hate has been let out of its cage; most memorably in Charlottesville, Virginia during the 2017 Unite the Right Rally where far-right protesters challenged the city’s decision to remove Confederate monuments; including a larger-than-life statue of Robert E. Lee atop his beloved horse Traveller.**

Most recently, Confederate flags were widely displayed during the January 6, 2021 insurrection at the US Capitol; representing today exactly what they represented 160 years ago. “The Confederate States of America and those who fought for it,” as Seidule concludes, “refused to accept the results of a democratic election [of Abe Lincoln] in 1860. They rebelled against the United States of America to set up a new country founded on the principle of white supremacy…”

Finally, on the contentious issue of monument removal, Seidule seeks out a moderate position informed by history; something I have tried to emulate in my own interactions with friends and family who spend less time with these things than I do—and are therefore, unfortunately, in my view, susceptible to “modern myth-making.”

“My job,” Seidule professes, “is not to tell communities if they should remove memorials to Lee, but they should study the circumstances that led to their creation.” In Robert E. Lee and Me, this is exactly what he has done.

* Here is a thorough summary of recent actions taken across the country to dispel the Lost Cause myth.

**Traveller’s remains, as well as those of Lee himself, are interred at Lee Chapel on the campus of Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. Seidule sees Lee Chapel as the “Shrine of the Lost Cause” and the epicenter of the “Lee cult.”