It’s hard to imagine it now, but Topanga’s peaceful, upscale neighbor Calabasas was once a lawless Wild West stagecoach town, with cattle rustlers, gunfighters and brutal frontier justice.

In the mid 19th century, this small agricultural outpost became part of the Flint, Bixby and Butterfield stage line that ran between Los Angeles and Monterey. Calabasas was suddenly on the map. For early residents of the Santa Monica Mountains and the West Valley, the stagecoach was the fastest way to travel—provided the traveler could afford the fare. It also brought news, mail, and new faces.

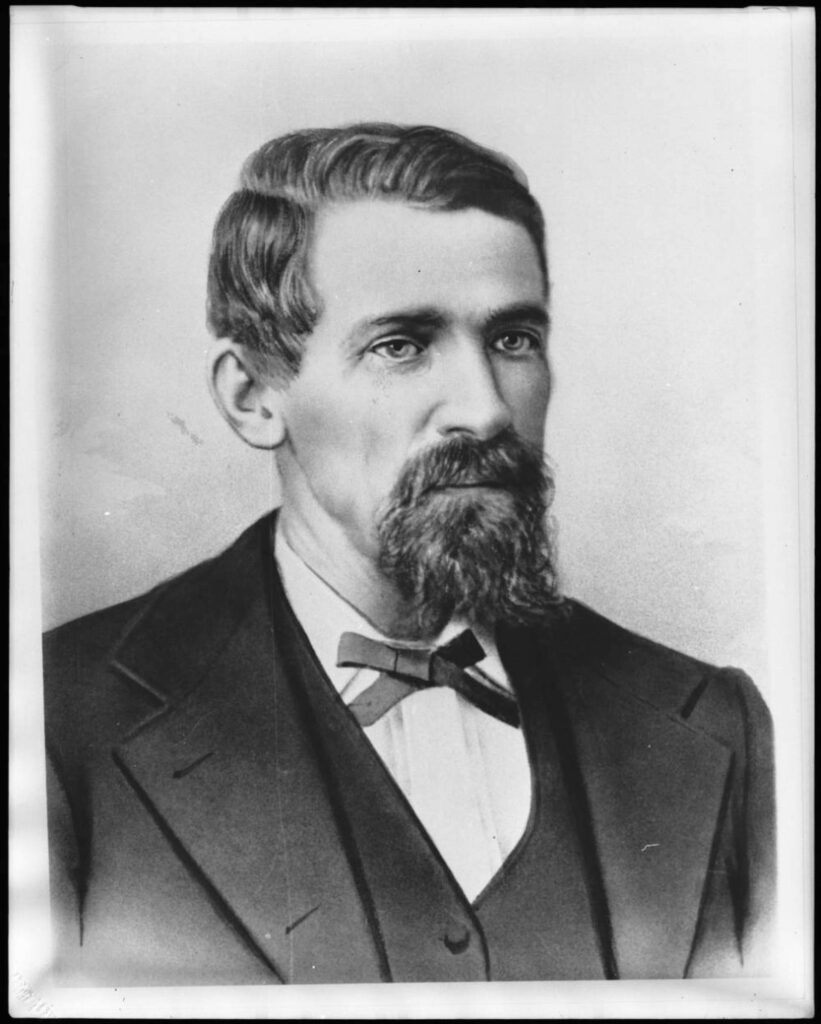

In the years following the arrival of the stagecoach, much of Calabasas and the West Valley came under the control of Miguel Leonis, an ambitious Basque settler who spoke neither Spanish nor English well, but was still able to build a fiefdom for himself, and fiefdom is the right word, because he ran his land like a medieval lord.

Leonis started out working as a shepherd on a ranch in the Calabasas area. He became a landowner just five years after arriving in Los Angeles, when he married the daughter of one of the three brothers who owned Rancho El Escorpion.

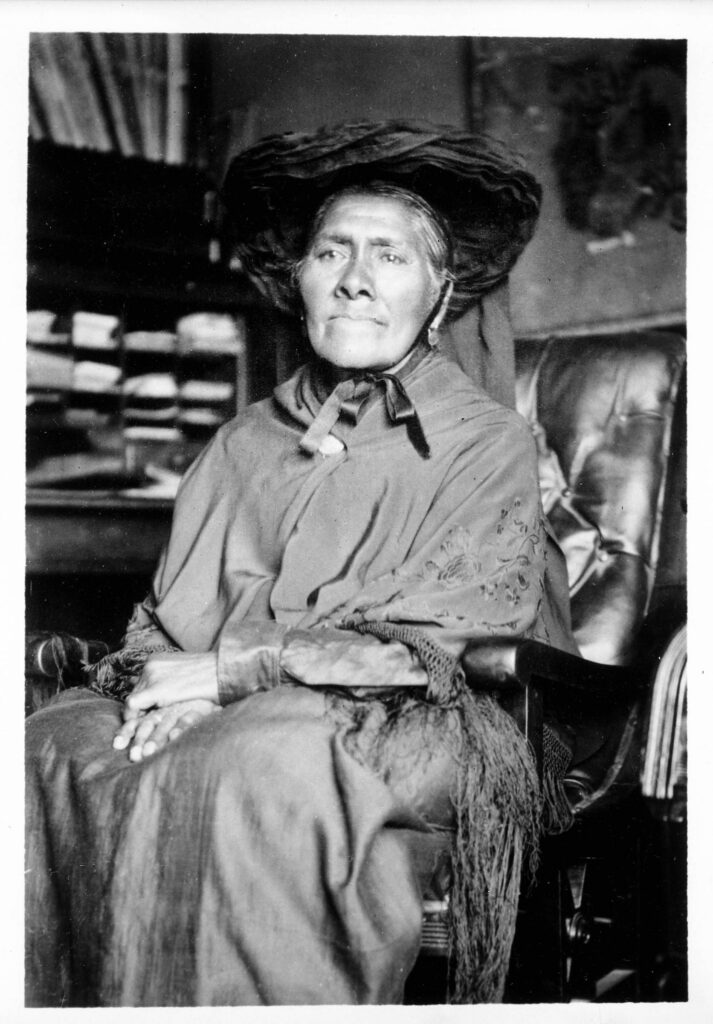

Espiritu Chijulla Menendez was the daughter of Odon Chijulla, the hereditary leader of the Malibu Chumash, whose family was granted the vast El Escorpion Rancho after the secularization of the San Fernando Mission.

Leonis gained control of 1,100 acres of the Rancho through his wife. He took up residence in an old adobe on the property and set out to build a kingdom.

The first house on the site of the Leonis Adobe was built in the 1840s, long before Leonis arrived in Calabasas. He rebuilt the house in the 1870s to include every modern convenience, from a Monterey-style veranda to an indoor kitchen.

Espiritu had a son from her previous marriage, but Leonis banned him from the ranch. The couple later had a daughter together, the one person Leonis is said to have truly loved, but she died young.

Leonis used Calabasas as his base of operations. He took advantage of the power vacuum created during the transition from Mexican territory to U.S. state to build what has been described as his own personal army of vaqueros—Mexican and Chumash cowboys. They enforced his claim on the land, and helped him to expand his holdings. When the U.S. government opened a wide swath of land to homesteaders, Leonis began building shacks everywhere he ran his cattle. He installed his employees in them as “homesteaders,” and staked a claim, terrorizing anyone who challenged him.

In the early days he was called El Basque Grande. Eventually he earned the name King of Calabasas. By 1875, Leonis was an absolute monarch, controlling lands that stretched from Lake Elizabeth near Lancaster, through the Mission Hills to the Santa Monica Mountains. He enforced his rule with violence and intimidation. Leonis forced out squatters and homesteaders, won legal challenges by bribing officials, and extended his holdings by a combination of brute force and cunning.

Soldier-turned-attorney Horace Bell chronicled many of Leonis’ activities, from setting fire to a neighbor’s property, to cutting fences and stampeding cattle through homesteads.

Historian Laura Gaye in her book Last of the Old West makes a valiant effort to make Leonis respectable by giving him an aristocratic family, but the epitaphs “freebooter, pirate and soldier of fortune” seem a better fit than “aristocrat.”

While he was unquestionably ruthless, Leonis maintained order. After his death in a wagon accident in 1889, Calabasas devolved into something that sounds like a spaghetti Western.

Accounts from the papers of the time are full of grisly barroom brawls, revenge killings, vigilante justice, and range wars between settlers and claim jumpers, and cowboys and cattle rustlers. One man lost an eye and had half of his ear bitten off in a barroom brawl, another was shot in the middle of a dance.

Between 1890 and 1900, there were seven murders in and around Calabasas, and numerous acts of violence, many of them related to land claims and property issues like right of way for cattle. In 1892, the murder of a Calabasas man named Charles Gannon who was shot after jumping another homesteader’s claim, became a national newspaper sensation, and put the Santa Monica Mountains on the map as a lawless outpost of the Old West.

Another high-profile story involved Frank Valdez, 17, who shot a Calabasas storekeeper named Michael Lorden, allegedly because the local Justice of the Peace offered him $100 to do it.

Against this backdrop of frontier violence, ordinary people struggled to make a life in an inhospitable environment. In her book Calabasas Girls, Catherine Mulholland chronicles the lives of her hardworking homesteader ancestors, the Ijams family, The Ijams helped found the first school and the first post office, but it was a hardscrabble existence. Mulholland’s book includes letters home from the two young daughters, who were sent to clean houses in Los Angeles and to harvest fruit as far away as Newhall to make money to support the family.

One of the biggest problems the homesteaders faced was a lack of reliable water. There were only two creeks that ran year-round and the well water had high concentrates of salt and other minerals. A pattern of severe and recurring drought in the 1860s-1890s caused wells and creeks to dry up. Crops failed and cattle died.

The drought subsided in the 1890s, and so did the era of lawlessness. A January 30, 1901 news story in the Los Angeles Herald marveled that “Calabasas, from which evil and crime formerly emanated daily, hourly and almost secondly, has evidently reformed…during the year not a man has died with his boots on and there has not been a single criminal prosecution in the township.”

It was a far cry from historian and frequent Leonis opponent Horace Bell’s assertion a generation earlier that “inhabitants [of Calabasas] killed each other off so steadily that a human face is a rarity.”

By the 1920s, Calabasas was home to Park Moderne, an artists colony, and one of the area’s first planned communities, carved out of an old homestead near what is now Calabasas High School, but the lack of reliable water prevented major development until the Las Virgenes Municipal Water District was established in 1958.

Espiritu lived with Miguel Leonis for 30 years, but it was a common law arrangement and she was left with almost nothing when he died. Leonis referred to her in his will as his “housekeeper”, and left the land he took from her to his brother.

A 16-year lawsuit ensued. Espiritu became the first American woman to successfully win a palimony suit. She died just a few months after her legal victory, but she was able to spend that time in her family home, with her son from her first marriage, Juan Menendez, who had been banned from the property by Leonis decades earlier.

Espiritu left the house to her son, who sold it to the Agoure family in the 1920s, the settlers who gave their name to Agoura Hills. It narrowly avoided being torn down and replaced by a supermarket in the 1950s, and much of the remaining property ended up becoming the 101 freeway, but thanks to a determined group of conservationists, led by a woman named Kathleen “Kay” Beachy, the house survived to become Los Angeles Historical Cultural Monument No. 1 in 1962.

It’s a beautiful house, one of the oldest in Los Angeles County. It’s not surprising that Miguel Leonis’ ghost is said to haunt the adobe, but if anyone has the right to spend eternity there it ought to be Espiritu, to whom the land truly belonged, and who was wronged but persevered.

Things to see in Calabasas

Old Town Calabasas is tiny, just a quarter-mile stretch of Calabasas Road, but it still reflects the city’s past as a stagecoach stop.

The Leonis Adobe is the centerpiece of Old Town. It’s a first rate living history museum that is open weekends only. Costumed docents lead tours and give interpretive talks on life in the 19th century. The property is home to a small but well kept menagerie of farm animals and a beautiful garden. 23537 Calabasas Road. The website features a virtual tour. www.leonisadobemuseum.org

The Sagebrush Cantina is next door to the adobe. It stands on the site of Juan Menendez’ forge—he was the village blacksmith, in addition to being Espiritu Chijulla’s only surviving child. The Cantina went from being a favorite local family restaurant and watering hole to a lifeline during the coronavirus crisis, offering drive-thru groceries and essentials like bread. It’s back to serving its popular Mexican and American comfort food menu, and it also offers live music every weekend. Live band Karaoke every Thursday, 7-10 p.m., is a big draw, so is Sunday brunch with live jazz. 23527 Calabasas Road, (818) 222-6062.

The Calabasas Farmers Market is a favorite with many Topangans. It takes place in Old Town every Saturday, from 8-1 p.m. Historic buildings in the plaza where the market takes place include a two-story store and dwelling that was the stage depot inn. It once provided rooms for stagecoach travelers and deer hunters, and is now home to shops. Next to it is a replica of the Calabasas garage built in 1921 by the Daic brothers—Joseph, Charles, and Al. Its current appearance owes more to being used as a movie set, than a gas station.

There’s one more historic stop in Old Town: Calabasas Creek Park, also run by the Leonis Adobe Association. This small park offers an opportunity to step back into the 1880s, sit in the shade on wrought iron park benches and watch the ducks dabble in one of Calabasas’ only year-round creeks. There is also a replica of the Calabasas jail and several Chumash aps—round houses made of reeds. Like the museum, the park’s hours are limited, but it is open on weekends from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. www.leonisadobemuseum.org/visitor-creekpark.asp.

The city of Calabasas has a history section on its website, as well as links to the community’s library, and the Calabasas Historical Society. Learn more at www.cityofcalabasas.com.

Great article, Ms. Guldimann.

Thank you, Ms Watts! Glad to hear from you!