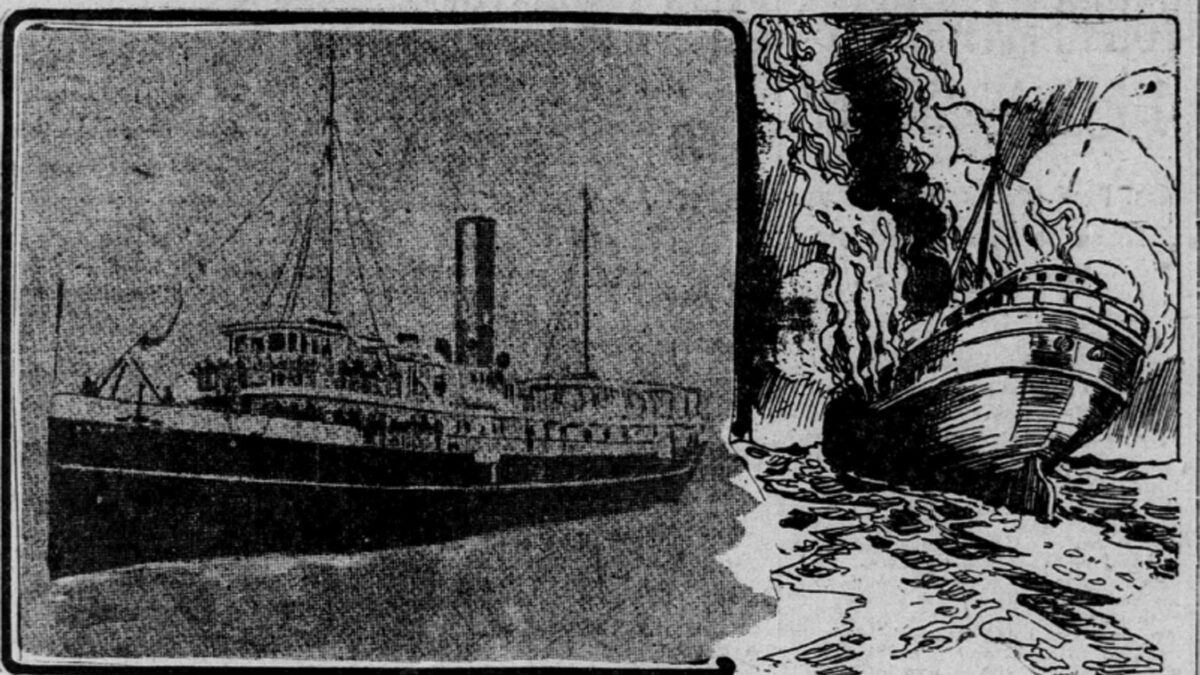

The steamship St. Croix sank off the coast of Point Dume almost exactly 112 years ago. The incident is nearly entirely forgotten now, but the dramatic disaster was headline news in 1909. Readers all over the country were left breathless by colorful accounts of the trials and travails of the 44 crew members and 82 passengers of the ill-fated ship. Everyone, from the captain to a six-month-old baby, was extensively profiled.

“I lost the ship, but thank God I did not lose a life,” Captain Fred Warner is reported as saying.

The baby, described as the “six months old heroine of the wreck” by the Los Angeles Tribune, offered no comment, but she, and a small white terrier named Sweet who also survived the wreck, each had their fifteen minutes of front-page fame. The story remained a sensation for weeks.

In the days following the first reports of the shipwreck, many newspapers surmised that the 240-foot wooden single-funnel steamer went down with “all hands.”

“The new Shelback-Hamilton Line steamer St. Croix was burned to the water’s edge to-night off Point Duma [sic], fourteen miles north of Santa Monica,” the Tribune article continued. “The steamer City of Topeka, which arrived at Redondo last night, reported passing the St. Croix aflame from stem to stern.”

The Delaware Pilot described it as “a holocaust at sea,” and reported that “One hundred people were burned to death, drowned or killed by the explosion of the boilers on the steamship St. Croix.”

The November 20, 1909 San Francisco Call provided the first news of the survival of the crew and passengers, but reports of the incident varied significantly, with some accounts describing the captain beaching the burning ship and others describing a harrowing trip by lifeboat—nine boats with fifteen people in each—through heavy surf to reach “Zuni” Cove. There’s a theory that this was Paradise Cove, based on a description of tall cliffs, but the late Malibu historian Ronald Rindge believed that Zuni was Zuma, and that the specific location was near the outflow of Zuma Creek.

Surviving the wreck was only the first part of the ordeal. A number of passengers and crew members were injured during the landing. One woman was caught between the hull of the ship and the lifeboat, crushing her legs. Moments later, she and her six-month-old child were reportedly nearly drowned when the lifeboat was swamped by heavy surf.

The Call reported that she and the baby, with the fourteen other occupants of the boat, were thrown into the water, but were rescued by her husband and two other men, who dived from the upper works of the burning vessel. Herbert, the six-year-old son of Charles Vellbaum, was saved at the same time by Edward Norris, a ship’s quartermaster, aided by Mrs. Grace Thomas, who proved herself a heroine.”

The survivors gathered on the beach and tended to injuries that included burns, contusions and broken bones. The Call reported that the first mate climbed the cliffs and walked all the way to the Malibu Ranch house at what is now the Serra Retreat in search of help. The rest of the crew and the passengers spent a wet and uncomfortable night on the beach. In some of the more colorful accounts a rancher with a race car, or alternately, a “secret service agent,” was the first on the scene and sent for help.

The glow of the burning vessel did attract attention and eventually ranch hands arrived with wagons and mule teams. All of the passengers and most of the crew opted to travel out on foot or by mule wagon. Those who stayed behind at the landing site seem to have fared better than their shipmates, although one crew member was described as “severely injured.” The Coast Guard cutter Perry arrived the next day and transported them to San Pedro. The injured man was carried on a stretcher.

In contrast, the journey by mule team seems to have been more traumatic for some of the castaways than the shipwreck. The only coastal route through Malibu in 1909 was along the beach. Passage depended entirely on the tides and weather—big surf or high tides could swamp travelers or leave them stranded. One of the St. Croix passengers recounted that the wagon drawn by the mule team overturned three times.

“I guess I’ll be alright,” she reportedly said. “But I do wish that I could get home. I’m bruised all over.”

Another account states: “The driver of this contrivance was picking his way along the beach in the darkness when his mules became frightened and swerved out toward the sea. The left forward wheel of the wagon struck a boulder; and the vehicle was violently shunted into the surf. The mules started to run and in an instant a big comber dashed over the wagon, drenching the occupants and rending terror to the hearts.”

The castaways appear to have been transported all the way to the ranch gatehouse at Las Flores Canyon, where a bonfire—described in one account as having been made of railroad ties from the Malibu railroad—provided warmth while they waited for transportation back to Santa Monica and civilization.

The newspaper accounts state that the steamship company did little to assist the victims, but that the police and fire departments, sympathetic residents of Santa Monica, and the reporters who were among the first to arrive at the scene provided food, clothing, and, finally, transportation for the victims. For the passengers of the St. Croix, the 36-hour ordeal was finally over.

This article is an excerpt from Topanga New Times editor Suzanne Guldimann’s latest book, Life in Malibu II, now available on Amazon or at the Adamson House Museum gift shop in Malibu.