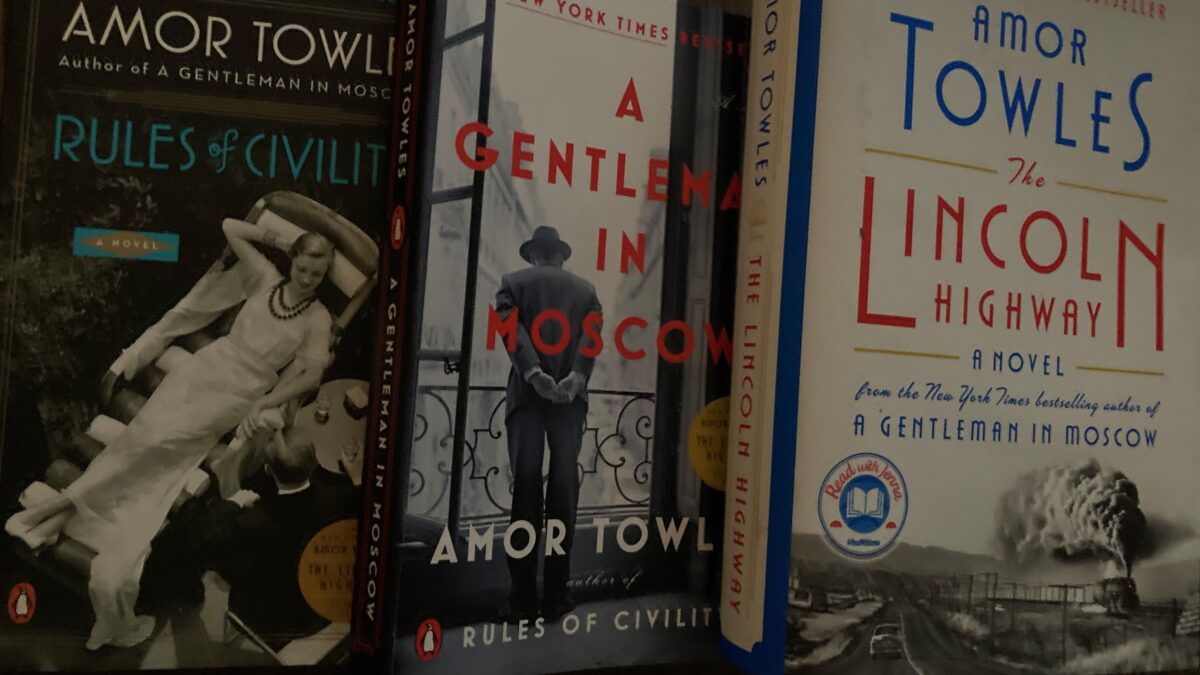

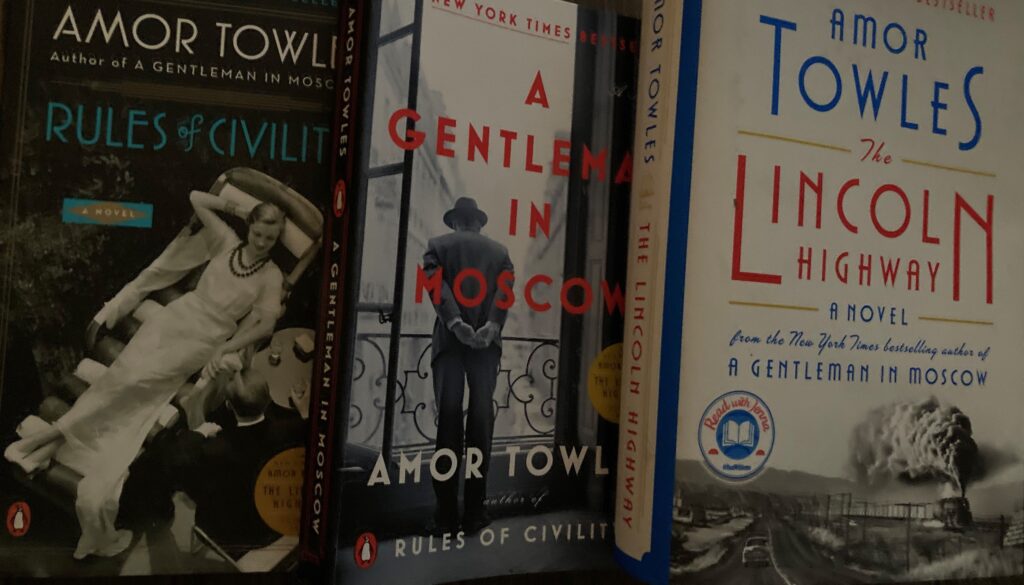

I cannot recall a time in my reading life when I became so quickly and thoroughly enchanted with a writer. Less than 100 pages into Amor Towles’ most recent and third novel, The Lincoln Highway (2021), I hailed Mr. Amazon to send along the other two.

The titular Lincoln Highway was dedicated in 1913 as the first transcontinental road running from New York City to San Francisco. It traverses 13 states; including Nebraska where the story begins.

With crackling prose, dialogue unburdened with quotation marks, and the inquisitive deployment of literary references, I joined 18 year-old Emmett Watson and his eight year-old brother Billy on a road trip in search of the mother that had abandoned them years earlier. It is June of 1954 and our ride is a 1948 Studebaker.

Like all good road trips, however, getting from Point A to Point B is not dependent upon the conveyance of a single vehicle. And, as anyone who has been on such an adventure knows, it is often the case that Point A to Point B is very often not the point at all.

Emmett and his uninvited traveling companions Duchess and Wooly are the recent residents of a reform school for wayward boys. Emmett has been released early because his father has died; while his two former bunkmates have stolen themselves away in a less official capacity.

The story is also about Sally who has been caring for Billy in the absence of his parents and big brother. Sally appears to have eyes for Emmett.

While on the road, the boys encounter saviors and hucksters, philosophers and vagabonds, good cops and bad, and a handful of like-minded rovers. Sally is the anchor that keeps them out of trouble… mainly.

Near the end of the journey, Emmett informs us that this may not be his last: “I do believe that the Good Lord has a mission for each and every one of us,” he reveals, “but maybe he doesn’t come knocking on our door and present it to us all frosted like a cake. Maybe, just maybe what He requires of us, what He expects of us, what He hopes for us is that – like His only begotten Son – we will go out in the world and find it for ourselves.”

That’s quite an endorsement; especially when the “leaving” in this tale comes about only because all the reasons to stay-at-home had frittered away.

There is also very little staying-at-home in Towles’ first novel, Rules of Civility (2011), set in 1938 Manhattan.

Living in a boarding house and with a day job clacking away on a typewriter, twenty-five-year-old Katey Kontent—whose last name is pronounced as if its owner is in a perpetual state of bliss—and her roommate Eve chance upon a distinguished gentleman-banker named Tinker Grey. As they share each other’s worlds, largely through the varied clubs and restaurants that characterize their respective rungs on the social ladder, the reader is compelled to wonder just what it is that makes money such a ubiquitous marker in American life.

Along the way, Towles reminds us that class and character are not as exclusively bound together as those in “high society” would have us all down here believe. In pondering the title’s reference, The Young George Washington’s Rules of Civility – of which there are 110 – we are encouraged to ponder which among them is more important. For example: not speaking with a full mouth (#98) versus the veracity of the words spoken after swallowing (#79).

Early on, Katey is invited to the posh living quarters of her new friend and is alerted—as is the reader—to what is to come. Chauffeured vehicles arrive at an apartment building attended by doormen. A black man named Hamilton operates the elevator. The doors of the lift are decorated with a “dragon-crested shield inscribed with the motto of the Beresford: FRONTA NULLA FIDES. Place No Trust in Appearances.” In high society, buildings that house the rich take on names and personalities of their own while Amor Towles uses the opportunity to let us in on the sham.

Through the course of 1938, Katey is bluntly confronted with her misguided assumptions. Rather than being disappointed, though, she instead longs for the sublime fantasy in which they have all collaborated. Realizing that her world and Tinker’s are not so different after all, Katy muses, “I just wanted a second shot at a first impression.”

While the “gentlemen” of Rules of Civility behave accordingly – at least in their visible presentations—Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov in Towles’ A Gentleman in Moscow (2016) is the real deal. Originally set in 1922 and spanning three decades of Soviet-era tumult, his “Excellency” suffers a fate much more pleasant than others of his day who carried such titles. Rostov is sentenced—by the “Emergency Committee of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs”—to the Metropol Hotel and “should you ever set foot outside the Metropol again, you will be shot.”

The intrigue that follows belies the supposed limitations of the singular setting and in the process, a mosaic is tiled over time upon the canvas of the hotel; a sprawling mystery space occupied by a few characters who come and go through the lobby’s revolving door and others who, like our protagonist, seem as permanent fixtures along with the chandeliers.

Gentleman sizzles with the same crisp sentences that have for me become the unmistakable hallmark of an Amor Towles novel. This is Towles’ account of the very beginning of a rather unlikely life-long friendship:

“Sure enough, while Mikhail was prone to throw himself into a scrape at the slightest difference of opinion, regardless of the number or size of his opponents, it just so happened that Count Alexander Rostov was prone to leap to the defense of an outnumbered man regardless of how ill conceived his cause. Thus, on the fourth day of their first year, the two students found themselves helping each other up off the ground, as they wiped dust from their knees and blood from their lips.”

To discover more words that dance such as these, simply turn to a random page of these wonderful books.

Enjoy!