For the past three decades, novelist Richard Russo has been commenting upon the human toll of the decline of small-town America. Along the way, he has opened a window into the emotional meanderings of white working-class men in an age dedicated to establishing the legal, political, and economic equality of just about every other demographic group in the country.

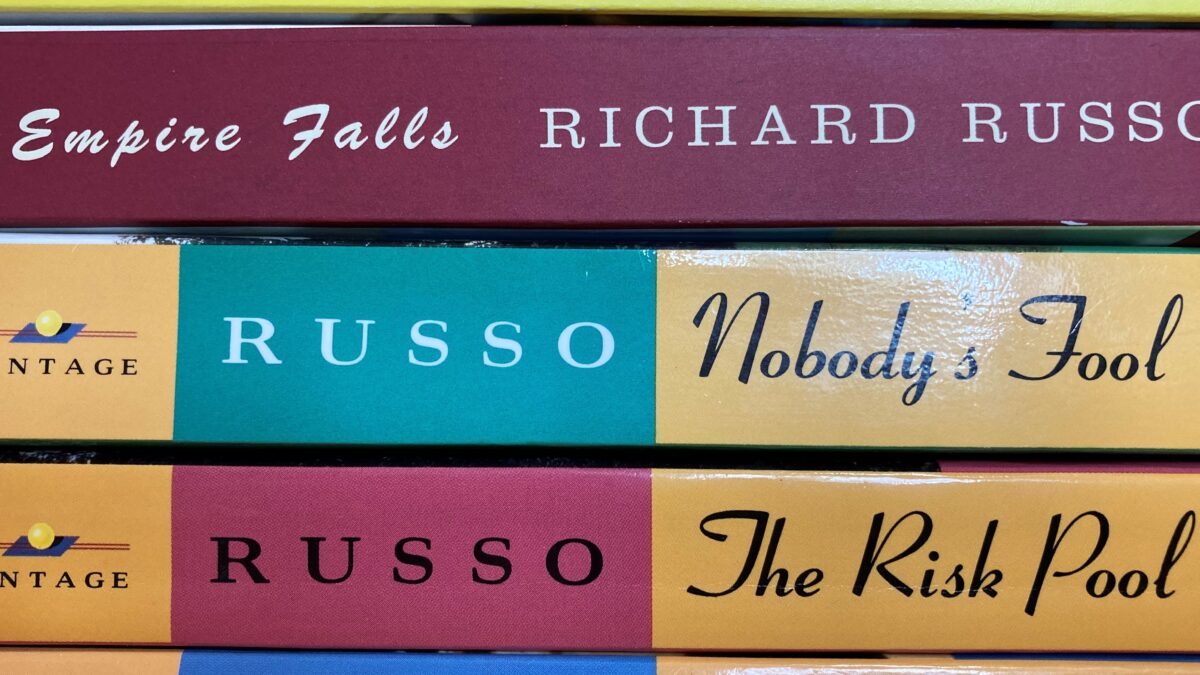

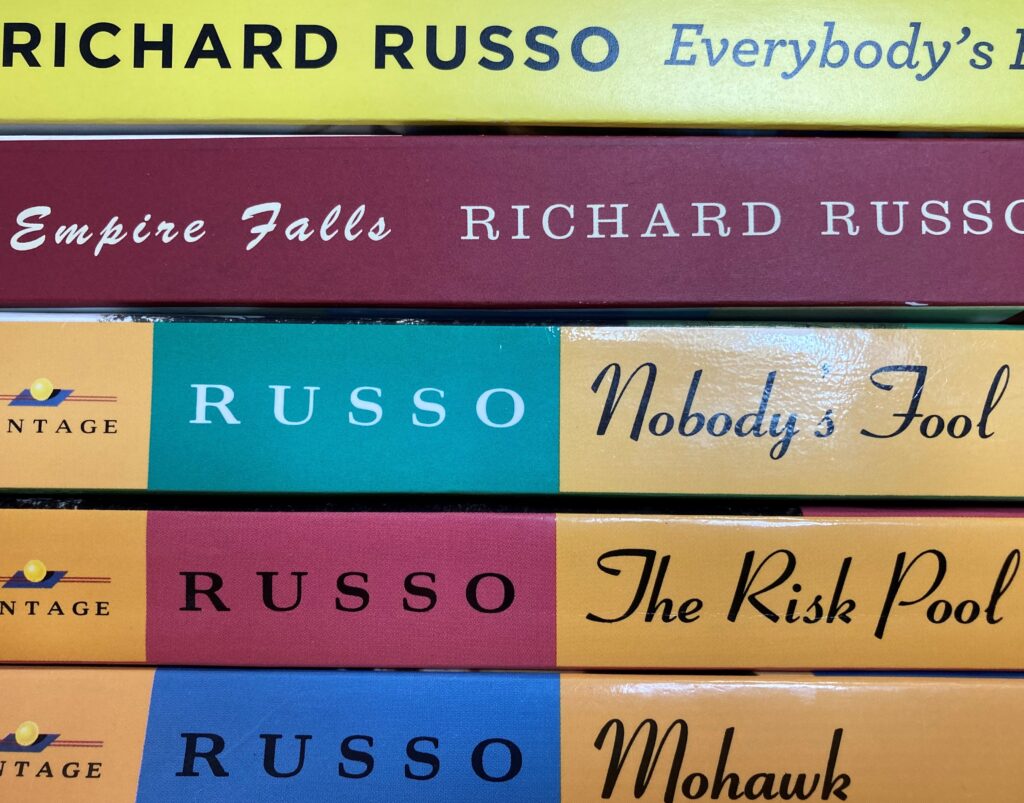

Beginning with Mohawk (1986) and followed by eight subsequent novels and a number of short-piece collections, Russo’s autobiographically influenced narratives go far in explaining the recent transformation of our country. This is particularly true as the Pulitzer Prize-winning author examines small-town life in Mohawk, The Risk Pool (1988), Nobody’s Fool (1993), Empire Falls (2001), and Everybody’s Fool (2016).

The small towns in Russo’s fiction are populated with a range of characters across multiple generations dealing with economic decline and one another. While his geographic scope is largely limited to the Northeast portion of the country—Russo grew up in Gloversville, New York—one can easily imagine similar tales unfolding throughout the Midwest and beyond.

Factories that once defined the lives of entire communities are shut down. Main Street windows are boarded up with plywood. Surviving businesses cater to a dwindling clientele, often befuddled with what has happened to their community. It seems as if everyone is struggling to pay the rent. Yet, despite the obvious misery, Russo imbues his characters with a soulful humanity that allows them to carry on… mainly.

Prominent in Russo’s work is the tangled relationship between father and son; a topic he manages with raw sentimentality and brute language. As many of us are familiar, young fathers raise their children with the desperate hope that they will not make the mistakes their own fathers made. Very often, though, as hard as we may try, there is no getting around the fact that our parents have put their mark on us.

Russo administers regular doses of social commentary. In more than one story, the local police officer is the same guy that bullied his way through high school. In one exchange, a bully-cum-cop brags that he turned out OK because he has a regular paying job while the guy whose lunch money he stole is not surprised in the least that the pathway to a career in law enforcement included a few lessons in brutality.

Sadly, it seems as if the few businesses that remain in Russo’s towns cater to despair even as many of the most hilarious moments in these books are lubricated with alcohol. A tragic melancholia seems to pervade Russo’s writing even as his protagonists plow through their days, fully aware of the desperation yet equally hopeful that their luck will soon turn.

Russo’s working-class humor is harsh. Its redeeming quality is that it accurately portrays how many Americans actually live; or, at least, once did. Indeed, in my experience, it would be insincere to portray this aspect of American life in any other way.

The pretense of presenting otherwise objectionable material as historically accurate falls short when explaining why I found myself buckled over with laughter at some of Russo’s crudest observations. The answer, of course, is that each of us has developed a sense of humor in tune with the society in which we were raised. Unfortunately, much of what was taken for humor when I was growing up was almost always offered up at the expense of others. Russo’s humor is potentially offensive. It is also quite familiar.

For many in our country, Russo’s scenes serve as a mirror and what they see is nothing to laugh at; except that sometimes laughter is all there is. The working-class man as we used to know him is an endangered species. The unforgiving reality, and Russo brings this home with an empty lunch pail and mud on its boots, is that a work ethic and a strong back no longer feed, clothe, and house a family of four. To be successful today often means adapting to rapid change; a skill anathema to the quiet predictable rhythms of small-town living.

Russo’s special gift is arousing sympathy for what appears on the surface to be rather unsympathetic characters; insecure men using foul language while drinking too much and neglecting their families. The protagonists in these stories, then, are the lone spirits who refuse to brood while stoically accepting things as they are.

Reducing Russo’s men to stereotypes, however, as I have implied here, is to miss the complexity, contradiction, and nuance which animate his creations. Throughout each of these novels, a dozen or so individual personalities are explored through their unspoken thoughts, motivations, and inhibitions. Disparate story lines are playfully and artfully woven together; reminding the reader that we all approach the world with our heads and hearts overwhelmed with the baggage of unique experiences, expectations, and the many judgments we make about others.

In this, some of Russo’s seediest characters are revealed as loving and caring human beings doing the best they can with the cards they have been dealt.

If America has evolved socially over the past 60 years or so, it has been in the direction of tolerating others and, in order to do this, we must avoid making hasty judgments. Yes, we should judge people by the content of their character. However, if we are to be tolerant, we should also consider the circumstances under which that character has developed.

In regards to the white working-class male of the species, Richard Russo offers an entertaining template to do just that.