Part III

On March 28th, 1979, one of the two nuclear reactors in south central Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island power plant suffered a partial meltdown, emitting low levels of radiation throughout the area, delivering the country its worst nuclear disaster and causing officials to urge the evacuation of all pregnant women within a 20-mile radius.

Jason Brooks’ mom was one of those women, just over halfway through her pregnancy.

Here is the conclusion of Jason’s “atomic” story.

Shortly after my Chernobyl trip, I would become more intimately acquainted with a different kind of disaster. This time nearly in our backyard. The Woolsey Fire of November, 2018. Residents of Thousand Oaks, Agoura Hills, Malibu, Woodland Hills, Topanga and other nearby communities need not be refreshed of the specifics of this recent peak moment of terror amidst the chaotic tapestry of wildfires increasingly befalling our Western environment. So many people lost homes and their life’s accumulations in that devastating 9-day blaze. One of them was a former colleague of mine, residing in nearby Corral Canyon, married with two small children. Disaster never felt more close to home and for the first time in my life I felt survivor’s guilt (quelled in part by raising funds and donations to make some small dent in helping my colleague’s family get back on their feet).

Fortunately, our Topanga was spared, though it remained under mandatory evacuation for those nine days while the blaze ravaged adjacent Malibu, fueled by the same southwest blowing winds that also shielded our little community. Niki and I stayed behind, listening to updates on our hand cranked radio while the power was out and subsisting largely on the eggs delivered daily from the chickens and ducks of our evacuated neighbor’s coop. Why did we become like those Samosely of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, staying behind and defying an evacuation order? In part because we had the semi-relevant experience of surviving in harsh outdoor environments and ham radio and weather monitoring skills; in part because we’re a little stubborn; and in part because our house is advantageously perched atop a crescent-shaped hill with a sweeping view over the entire western flank of Topanga, bounded by Calabasas Peak in Red Rocks State Park—enabling us to see beyond a great shield of mountains where the fire was and where the winds were blowing. Geographically, visually, we would have had ample warning to flee using one of the several escape routes available to us had the fire decided to shift eastward from Malibu. Not a decision many would make, but we believed our risk tolerance was well calibrated.

But why mention a Southern California wildfire in the midst of my journey through atomic curiosities? Well for one, the Woolsey Fire began on the site of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory (also once known as Rocketdyne), a facility located nine miles north of my home that once tested rocket and nuclear reactor technology throughout the Cold War era until it was shuttered in 2006. In 1959 a small nuclear reactor there suffered an accidental meltdown, with an estimated release of radioactive contamination even greater than the Three Mile Island incident, but due to its classified nature and relative isolation from nearby population (at the time), the details of this event were kept secret for decades. A recent study uncovered the fact that the Woolsey Fire had effectively “stirred up” some of that original contamination, with several areas near the perimeter of the facility being found to contain small amounts of radioactive particles. While not anywhere near the scale of disaster as Chernobyl or as public of a disaster as Three Mile Island, this would be another peculiar intersection for me and atomic history.

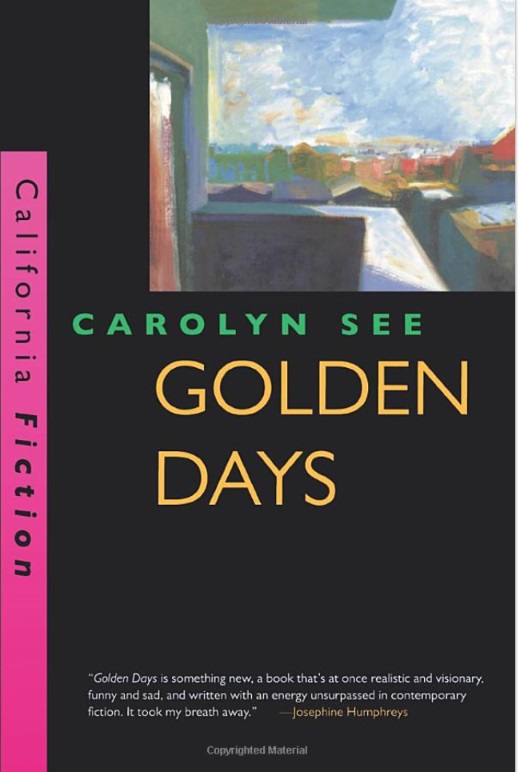

Again, the Woolsey Fire became the setting where I discovered an even more peculiar coincidence: Near the end of the nine-day evacuation order, with the intense and high-risk part of the fire over with, a few of those who remained in the neighborhood got together at a neighbor’s house for a kind of “survivor’s” dinner. “So which house is yours?” one of the guests inquired. After we told them about our unique metal-sided house up a steep driveway near the end of a dead end road, the neighbor replied, “oh, Carolyn See’s old house.” Niki had been aware that our house was once occupied by a well-known author named Carolyn See in the 1980s and 90s, and who had passed away a year earlier in Santa Monica where she spent the remaining decades of her life. But what we then learned was that the setting of one of her most well-regarded books was not only our idyllic separate-from-Los-Angeles paradise of Topanga, not only was it in our “tough” to reach neighborhood of Old Canyon (her words), but in our very house—and it takes place before, during and after a nuclear holocaust! In one edition of the book, the cover image is a painting of our front porch. One can find online a video interview conducted by a public broadcasting network with Carolyn from 1989 that is clearly filmed in our backyard.

Even more coincidental with the moment I discovered this coincidence of “atomic fates” was that one her inspirations for writing a novel about surviving nuclear war in our house was her very real experience of surviving a wildfire that ravaged her neighborhood, burnt down the neighbor’s house and, according to an interview with her, sent her fleeing her house amidst smoke and flame, fearing her house, too, was gone, only to see the smoke clear and see the structure still standing. In the novel, she wrote about preparing for the nuclear fires by putting buckets of water at each of the four corners of the house—just like we had done during Woolsey. She wrote of walking along the 200-foot crescent hill behind the house, searching the landscape for signs of hope, just as we’ve walked that crescent hundreds of times, including during Woolsey to survey the mountains for signs of shifting winds and encroaching flames. It was like discovering I was living in a version of that favorite Children of the Dust novel of my youth.

Of all the dwellings in the world that I would end up calling mine. Of all the people in the world that it would end up sheltering: A boy born amidst a nuclear scare and weaving his way through life amidst the strands of atomic history, then discovering amidst his own trial of flame, that a similar trial of flame decades earlier would inspire a famous author to write one of her most acclaimed stories about surviving nuclear war from this very place. The title of her book: Golden Days. A title that was in reference to this line from the 17th century epic poem by John Milton, “Paradise Lost”: “the world shall burn, and from her ashes spring New Heaven and Earth, wherein the just shall dwell And after all their tribulations long See golden days…” [Capitalization his, and I can’t be alone in noticing the coincidence is his capitalizing See and Carolyn’s last name.]

Now here I am, just two years into my fifth decade of life (I’m 42). Society seems to be fraying into strands, a new war has befallen the world (cold or hot, depending on one’s location), the star of my childhood favorite movie, Terminator 2 (Arnold Schwarzenegger, also former governor of the state I would move to), is issuing an eloquent plea for sanity and resistance to the people of Russia, and Chernobyl is again in the news as the Russian army has seized, then retreated from the Exclusion Zone (but not without disrupting the irradiated soil, and apparently karmically causing a wave of acute radiation sickness among the invaders).

I am hurrying to finish this story from our house upon this crescent hill in Old Canyon, Topanga, preparing to depart again toward Ukraine—but this time, not because of anything atomic (I hope). While I have no connection to Ukraine other than my one time pilgrimage to its most infamous tourist site, I feel a “call of history” to do something to help the human victims of this new and atrocious war. Perhaps too, it is also a “call to meaning” that many of us facing middle age feel. Either way, even if it is a small thing, I feel compelled to be, as another contemporary author and philosopher, Roman Krznaric has written, “a good ancestor future generations can be proud of.” So rather than take a “conventional” vacation this year, I’m instead spending a similar amount of time and money and teaming up with a Ukrainian-born American colleague and heading to Hungary to help with refugee transportation and resettlement efforts due to the war.

I hope it will not make for more coincidence that my “atomic story” begins and ends with atomic disaster. No, I hope that while I flirt on the doorstep of a nation embattled under the mere “conventional” weapons of an otherwise nuclear superpower, that I nor anyone else should witness its maniacal leader use those nuclear weapons to “become death, the destroyer of worlds.” How tragic for all, and strange for me, that such an end would be.

On the first page of Carolyn See’s Golden Days she writes, “most of us have just one story in us; we live it and breathe it and think it and go to it and from it and dance with it; we lie down with it, love it, hate it, and that’s our story.” Maybe that’s most of us. Maybe that’s me too. And maybe this story I write is it, but I’m not sure I agree. My best friend and I once traveled to Iran, just months before their 2009 “Green Movement” preceding the Arab Spring. At one point, we found ourselves in the country outskirts of the city of Shiraz, drinking bootleg wine of the same name, talking through a translator to an Afghani refugee about his incredible ordeal fleeing Taliban persecution. As we parted ways at the end of a long night of sharing tales from one another’s galactically different lives, the man shook our hands, looked us in the eye and said one final thing through the translator, “life is stories.” I think I have more than one story, perhaps many. Perhaps I agree more with the American poet Walt Whitman when he wrote, “I contain multitudes”.

Or maybe Carolyn was onto something as she wrote from the house I would later come to occupy. Maybe we really do have just one story? Maybe that story is whatever story we have at the moment: the one we tell to make sense of ourselves and integrate with time and history. As another American writer, John Barth, wrote, “your life story isn’t your life; it’s your story.” Perhaps rather than “Forrest Gumping” my way through atomic moments, I’m more of a “Slumdog Millionaire”, coming to realize that all the curious things I’ve experienced in this past life have been as Winston Churchill once famously said, “walking with destiny… but a preparation for this hour and this trial.”

On the last page of her fictional book, Carolyn See writes about the residents of Topanga who lived beyond the dark days of nuclear war, “there was a race of hardy laughers, mystics, crazies, who knew their real homes, or who had been drawn to this gold coast for years, and they lived through the destroying light, and on, into Light ages.” Well, fellow hardy laughers of this real world Topanga, and elsewhere, I hope amidst whatever destroying light you and the world may see, that we can all continue to tell our stories on golden days.