How a Victorian Hobby Preserved More Than Memories

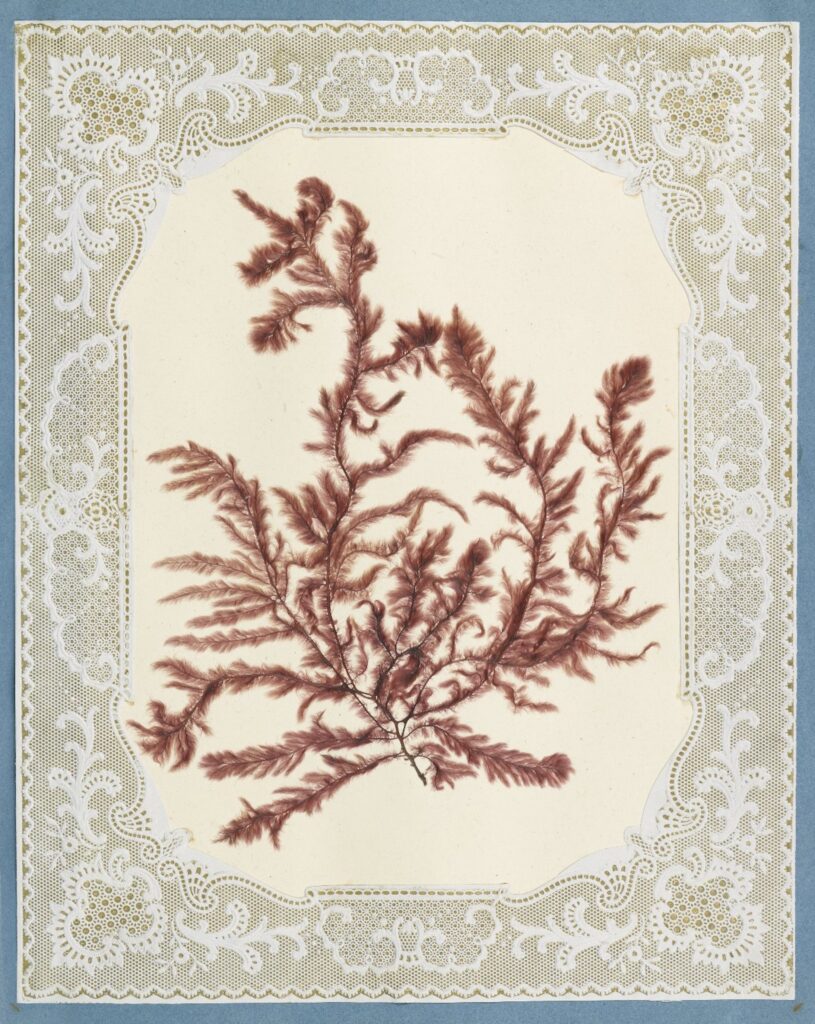

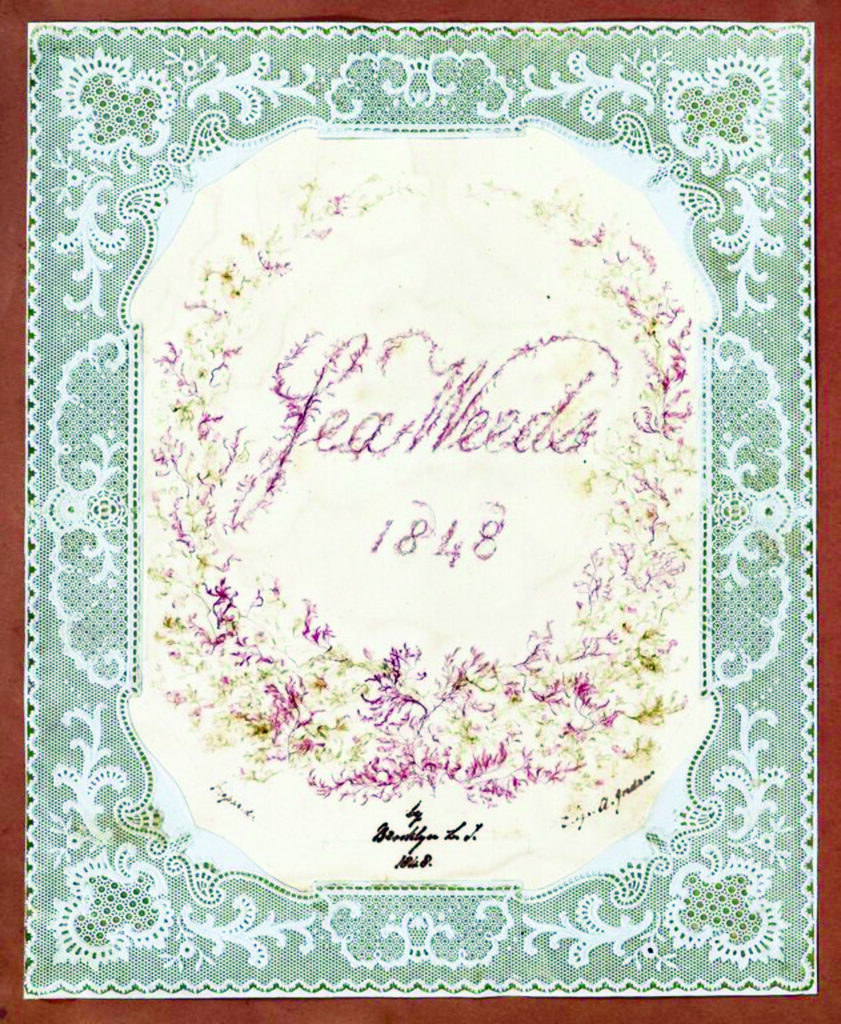

The Victorians were big on seaweed. Collecting it was a hobby deemed suitable for both gentlemen and ladies, and ladies embraced it with energy, collecting samples, arranging them in artistic patterns or in scientifically labeled rows, and pressing them flat in special albums.

This was a rare activity that was intellectually challenging while still being respectable, and it didn’t require a chaperone—a rare breath of freedom for a generation and class of women blessed with wealth and leisure time, but hindered by social mores and inconvenient clothing. Swimming required modestly concealing oneself in a wool bathing dress and entering the water from the privacy of a “bathing machine.” Collecting seaweed, however, gave a lady an excuse to hitch up her skirts and petticoats without risk of censure, and enjoy a peaceful hour or two on the seashore. No wonder collecting seaweed was popular.

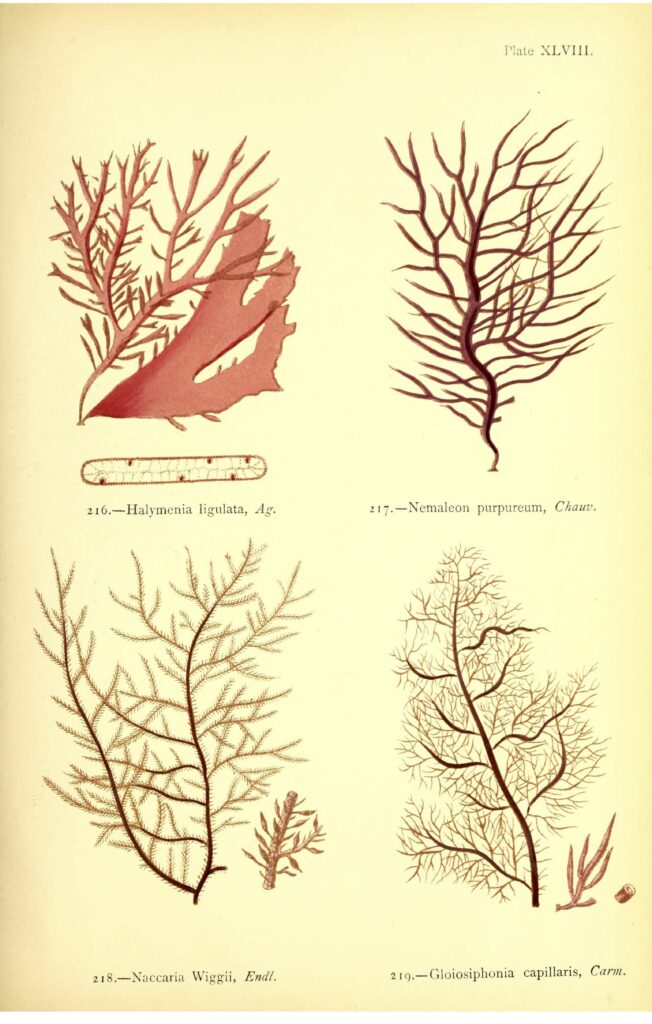

A dedicated woman seaweed collector might even be taken seriously for having scientific aptitude. British seaweed collector Margaret Gatty published an encyclopedic scientific work entitled British Sea-Weeds in 1863. It remains a remarkable work of scholarship. In 1896, Weeksia, a genus of red algae found on the California coast was named for an amateur naturalist named Mrs J. M. Weeks —much to her embarrassment. This self-effacing lady responded, “I am quite in earnest in not wishing my name attached to any plant!”

deemed suitable for both gentlemen and ladies, and ladies embraced

it with energy, collecting samples, arranging them in artistic patterns

or in scientifically labeled rows, and pressing them flat in special

albums

Seaweed collecting was more than just a passing fad. Its popularity peaked in the mid 19th century, but the hobby endured for more than a century, and there were passionate collectors all over the world. The West Coast provided a treasure trove of marine algae, with nearly 800 species. Collectors ranged from university phycologists—the official name for those who study algae—to entrepreneurs who gathered seaweed to sell as souvenirs. An 1887 Los Angeles Times article describes “delicate seaweeds…collected and arranged in tasteful designs,” that were “sold to tourists in vast quantities.”

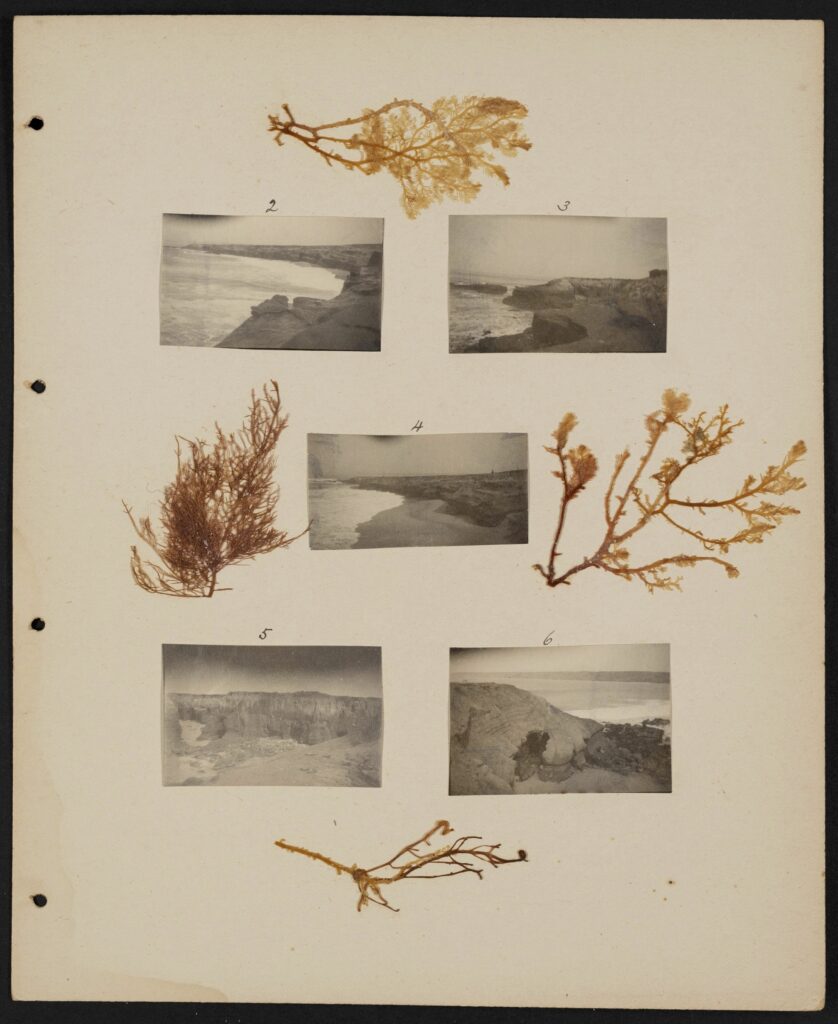

Serious California seaweed collectors included Ellen Browning Scripps, the journalist, suffragette, and venture capitalist whose life began in England in poverty and ended in San Diego with philanthropy on a grand scale. In 1903, she established the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla. The Institution’s archives still contain two albums of seaweed gathered by Ellen and her half sister Eliza “Virginia” Scripps. The specimens are carefully labeled by hand and include a selection of photographs detailing the locations of the samples. Scripps is also home to a formidable collection of pressed and mounted seaweed donated by pioneering biologist Mary Snyder.

Until recently, seaweed collections were mostly a curiosity. Now, old archives and forgotten boxes in the basements of institutions have become an important source of research material. Old collections are revealing new surprises.

The Ocean Memory Lab at the Monterey Bay Aquarium specializes in obtaining data from archived specimens, from turtle shells to seabird feathers.

Accurate ocean data only goes back about 80 years, but archived materials can potentially open a window on the past, a time before records were kept, a time before ubiquitous anthropogenic pollution.

The Ocean Memory Lab, developed by director Kyle Van Houtan, is already exploring the potential in pressed seaweed collections, and the first major study using this resource yielded surprising results.

The 2020 study, led by Emily Miller and co-authored by Van Houtan, analyzed nitrogen isotopes in pressed marine algae specimens collected on the Central Coast of California between 1878-2018. The research team found evidence that the catastrophic mid-century collapse of the sardine industry on the California Central Coast—the one memorialized in John Steinbeck novels like Cannery Row—correlates with a decrease in upwelling, an essential process that brings cold, nutrient-rich waters from the deep Pacific Ocean into the coastal zone.

While overfishing and changes to ocean temperature were the main contributors to the collapse, this new discovery adds nuance and provides important insight. It may also help researchers predict the future health of critically important marine ecosystems.

“Our case study suggests marine macroalgae from herbaria are an underused resource of the marine environment that precedes modern scientific data streams,” the researchers conclude.

“Macroalgae herbarium collections provide long-term ocean records from the nineteenth century in most of Europe and North America or even centuries earlier in Germany and Italy.”

That’s a vindication for the seaweed collectors, and especially for the serious women collectors, who were excluded from the main scientific discourse of the time, but who nevertheless found an outlet for their curiosity and a way to make a lasting contribution to science. n

DIY Seaweed Pressing

Seaweed pressing may no longer be in vogue but it still has enthusiasts and it’s fun and easy to do, and the results can be truly beautiful. This is an activity that combines science and art and can be enjoyed by all ages.

No permit is required for gathering seaweed in California, but there are areas where collecting is not permitted, like the Point Dume Marine Protected Area. Always check first. There is no need to take living seaweed, the pieces that wash up with the tide offer plenty of variety.

Keep the seaweed damp on the way home. It’s easier to work with when it hasn’t dried out. Place a piece of watercolor paper in about a half inch of cold water— a baking dish or pan works well. Rinse the seaweed, then float it into place on top of the paper. Carefully drain out the water. Tweezers, toothpicks, and paintbrushes can be used to finetune the arrangement. No glue is needed. Naturally occurring algin in the seaweed will help it to bond to the paper.

When the seaweed is arranged, place a piece of baking parchment or hardware cloth on top. Sandwich the paper between cardboard, and place between something flat— cookie trays or scraps of plywood work well. Stack something heavy on top: bricks, garden pots, or a pile of books all work well. Leave for at least 24 hours—thicker seaweed can take several days to dry; thin pieces will usually dry overnight. Carefully un-sandwich the paper when the pressing is dry. Several sheets of seaweed can be pressed at the same time, but be careful to layer each between parchment paper and cardboard. Good guidebooks for ID-ing seaweed include Pacific Seaweeds by Louis Druehl and Bridgette Clarkston and Seaweeds of the Pacific Coast: Common Marine Algae from Alaska to Baja California, by Jennifer and Jeff Mondragon. The iNaturalist app is also helpful, although getting a definitive match can be a challenge—there is an astonishing array of species right on our doorstep.