If I be waspish, best beware my sting

—Shakespeare

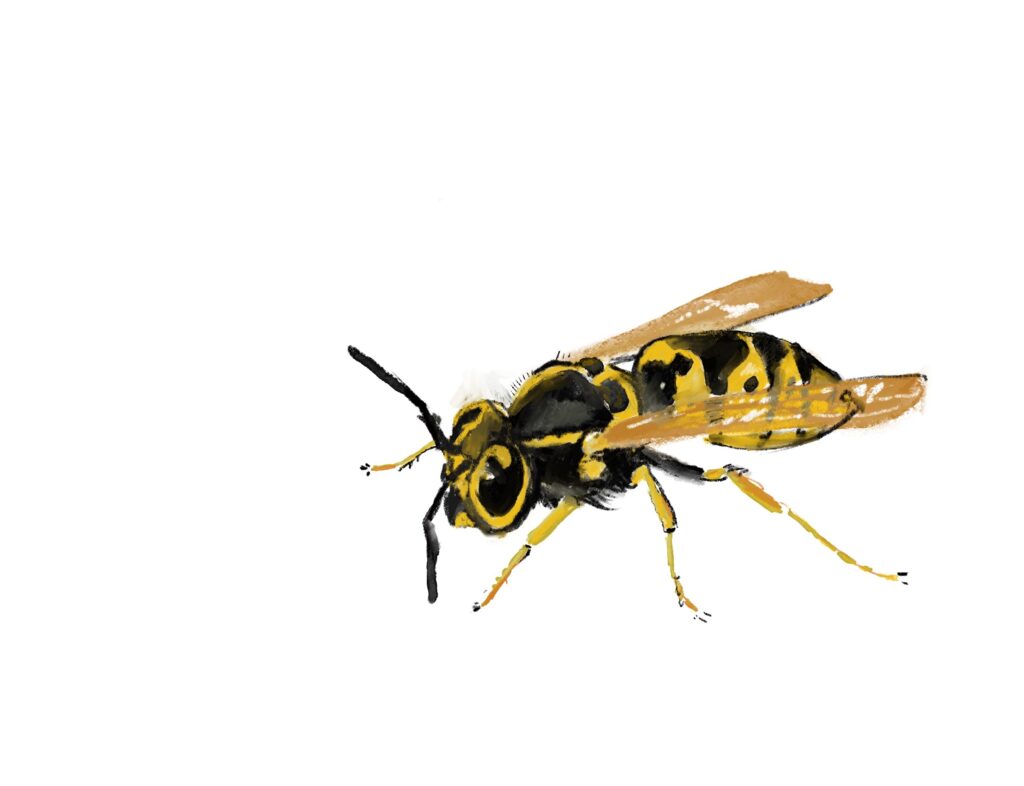

Say the word wasp, and most people think of the yellowjacket. This small insect, only a little bigger than a honey bee, has the well-earned ability to inspire fear and respect in animals many times its size. The yellowjacket’s distinctive yellow and black stripes warn of a formidable sting. They are such an effective deterrent that other species have evolved the same colors as a disguise and protection.

This is the fierce, aggressive wasp that has designs on your sandwich or your drink at a picnic. It’s the one that stings for seemingly little provocation—perhaps one has strayed too near the wasp’s nest or else the wasp simply doesn’t care for its victim’s attitude. This is the wasp that keeps stinging until it is satisfied that its opponent is running away as fast as possible. It is fierce, and golden, and determinedly waspish. Poets sing the praises of bees; no one sings the praises of the yellowjacket, but perhaps we should, because this is a remarkable insect.

There are several species of yellowjacket in the Santa Monica Mountains—they are all members of the order Hymenoptera, suborder Apocrita. The most common are the native Western yellowjacket, Vespula pensylvanica, and the invasive European or German yellowjacket, V. germanica. To tell the difference, one needs to look them in the eye—something most of us would rather not do. V. pensylvanica has a yellow ring around its eyes; V. germanica does not. Both are aggressive, and both sting—and sting, and sting. Western yellow jackets build their nests in the ground, using rodent burrows, but they can also set up shop between walls, or ceilings in houses or outbuildings. German yellowjackets prefer to nest off the ground, in trees but also in attics, wall spaces, woodpiles and outbuildings.

Yellowjackets are social insects, like honeybees. Workers build a hive of hexagonal cells made not from wax but from paper made from plant fiber and saliva. They tend the queen, care for the larvae, and hunt for water and food. Like bees, they have what is described as “extreme social behavior,” including a highly structured and cooperative social hierarchy and caste system. Although each wasp only lives for a few weeks, research shows they learn from experience and can communicate information to each other.

Yellowjackets are opportunistic foragers, feeding on nectar, sap, fruit, insects, caterpillars, and carrion. They are also experts at crashing picnics, earning them the name “meat bees,” but they are equally attracted to sandwich meats and sweet sugary drinks.

Colonies are seasonal. Each one begins in the spring, when a queen, fertilized the previous year, emerges from diapause—the insect version of hibernation. She builds a small nest and raises the first few workers on her own, then turns her attention exclusively to growing the colony’s population. By the end of summer, a successful colony can contain hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands of wasps.

Not everything is intimidated by the yellowjacket. In the Santa Monica Mountains, Western badgers, skunks and raccoons—all equipped with thick fur and long claws, will dig out a yellowjacket nest in pursuit of protein-rich larvae—the risk of getting stung outweighed by the promise of a tasty meal.

Yellowjacket activity and population numbers usually peak in August and September. The workers are in a frenzy of activity in late summer, raising the next generation of queens and ensuring the future for the next colony. As resources become scarce, wasps are more likely to come into contact with humans in search of new sources of food and water.

Cold weather helps regulate the yellowjacket population. Yellowjackets cannot fly when the temperature drops below 53 degrees, and unlike honeybees, the colony does not store food for the winter. Almost all of the wasps except the next generation of queens will die during the winter. Climate change could change that. In more temperate areas, including parts of coastal Southern California, colonies can sometimes overwinter, surviving for more than one year and growing to contain many queens, tens of thousands of workers, and hundreds of thousands of cells. The western yellowjacket has become a major pest in Hawaii, where perennial nests are a problem, and yellowjackets have successfully outcompeted the mild-mannered native wasps, and are busy terrorizing the inhabitants.

Why would anyone sing the praises of this insect? Because this species plays an important role as a pollinator and part of nature’s clean up crew, and because this tiny insect has the power to strike fear in our hearts. Even with all of our chemical weapons and technological advantages we have little power to vanquish this fierce, determined, jewel-like insect from our lives. It is a force of nature, one that isn’t always easy to live with, but which deserves our respect and understanding.

Coping with yellow jackets.

Peaceful co-existence with yellow jackets isn’t always possible, but there are ways to reduce conflict:

Keep yellowjackets out. The best way to prevent problems with wasps in the home is to seal up holes and gaps. Wood filler, and hardware cloth are good choices.

Remove attractants. Clean up outdoor cooking areas, cover garbage containers, and pick up fallen fruit in backyard orchards. Open and unattended drink containers attract wasps and can result in a painful sting on the lips if the wasp is undetected, and yellowjackets are famous for their love of picnics—all uneaten food should be carefully covered.

Be aware of wasp activity. A sudden increase in the number of yellowjackets in the garden may indicate that there is a big colony nearby. Simply sitting still and observing where the wasps are headed can help identify the source. Workers will use saliva to moisten soil, making it easier to excavate more room for their colony. They will also use this technique on structures. Patches of damp soil or discolored plaster can be an indicator of wasp activity. Yellowjackets will fiercely defend their colony. Staying a respectful distance away from a nest can help prevent problems.

Look before digging or disturbing the soil. Gopher and ground squirrel tunnels are favorite yellowjacket nesting locations. Checking for the presence of wasps before starting to dig or using equipment like weed whips, mowers or cultivators can help prevent releasing an angry army of wasps.

Get help. Most yellowjacket stings occur when humans or pets stay too close to the wasps’ nest. If that nest is in or near a house, exterminators may be needed. It’s important to call a professional. Removing a yellowjacket nest is not a safe DIY project.

Run away. The best thing to do when faced with a swarm of angry wasps is move away as quickly as possible. Yellowjackets release a “fear” pheromone when they sting, which attracts more defenders. Leaving the area is the best way to prevent multiple stings. Make sure to wash all clothing before wearing it outside again.

The sting. Unlike bees, wasps can and will sting multiple times. Yellowjacket stings are painful, described by biologist Justin Schmidt, creator of the Schmidt Pain Sting Index, as “hot and smoky, almost irreverent. Imagine W. C. Fields extinguishing a cigar on your tongue.”

For most sting victims, the pain lasts for around ten minutes, but for those unlucky to have a sensitivity to wasp venom, the pain and swelling can last for days. Allergic reactions are not common, but a yellowjacket sting can cause anaphylaxis, and multiple stings can be a serious medical emergency even if the victim is not sensitive.

An EpiPen is essential equipment for anyone allergic to bee or wasp stings, but even without an allergic reaction a sting can cause serious irritation and pain.

Ice is considered the most effective home treatment for the pain and itching. Hydrocortisone cream and calamine lotion are popular commercial remedies. A topical analgesic like lidocaine may also help. So can an antihistamine like Benadryl. A trip to the urgent care may be needed if the swelling is extreme or persists for more than a few hours.

Coexistence. Like many biting and stinging insects, yellowjackets are essential pollinators and a key part of the local ecology. Being aware of them and taking safety precautions can help prevent unwelcome encounters, but it won’t stop all bites or stings from occurring. This insect is the living definition of waspish. Yellowjackets are part of life in our mountains, guests at the picnic of life like all of us, whether we like it or not.

Wow Suzanne Guldimann has taken it up another notch! She’s a wonderful writer and naturalist, and a skilled artist too! I loved her illustrations in this article. Nice touch!