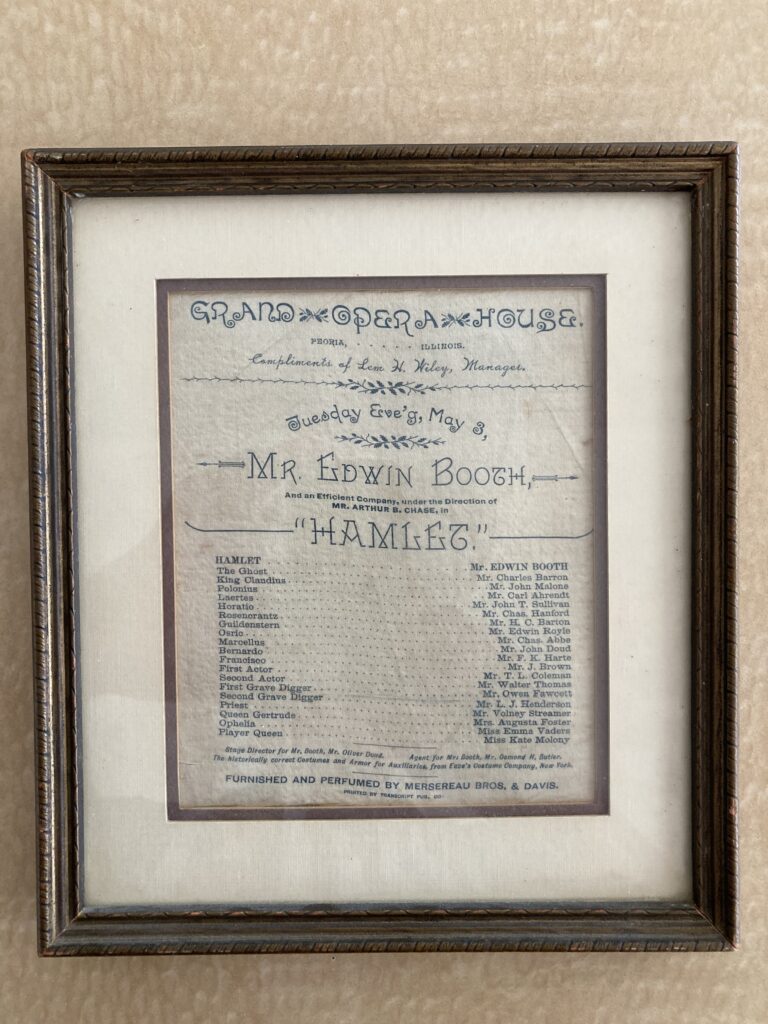

in Peoria, Illinois on May 3, 1887. While the year is not printed, the playhouse was built in 1882 and Booth died in 1893.

The only years in this span in which May 3 was a Tuesday were 1887 and 1892. Given that Booth had a stroke in 1891

and that I was able to confirm that Booth performed in Indianapolis on May 5, 1887, just over 200 miles from Peoria,

and accessible by train… 1887 it is. Photo by Jimmy P. Morgan

I have reason to believe that someone in my family tree attended a play at the Grand Opera House in Peoria, Illinois on Tuesday May 3, 1887. The evidence for this suspicion rests with a relic that has made its way to me as my mother ponders the next, less-cluttered, chapter of her life. Mounted on an old piece of cardboard and yellowed masking tape framed with dark wood under a thin piece of glass is a silky playbill announcing the performance of Edwin Booth in the role of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

On a recent visit, I recorded my mother walking around her Victorian home on one of the seven hills overlooking downtown Cincinnati and the Ohio River. In each clip, she describes the provenance of each item and its connection to our family; silver spoons, a quilt, a painting, a sculpture, a piece of old familiar furniture. In this way, she is ensuring that each item is properly associated with its back-story. She is also taking notes as to which of her children and others are best-suited to care for and appreciate them as she has.

Actually, it was during this tour of her home that I admired the Edwin Booth playbill. A few months later, it arrived in the mail.

I’ve since learned that playbills printed on silk were typically reserved for special occasions. And, given that Edwin Booth was perhaps the greatest Shakespearian actor of the nineteenth century; his appearance in Peoria clearly rose to the level of silk.

Unfortunately for Edwin, at least as far as history is concerned, his celebrity has been dwarfed by his brother’s infamy. On the evening of April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth used a single-shot derringer handgun to shoot President Abraham Lincoln in the back of the head. Lincoln died the next morning, only six days after General Robert E. Lee had surrendered his Army of Virginia to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia, ending the American Civil War; and, with it, the cessation of four years of carnage that had taken upwards of 620,000 American lives.*

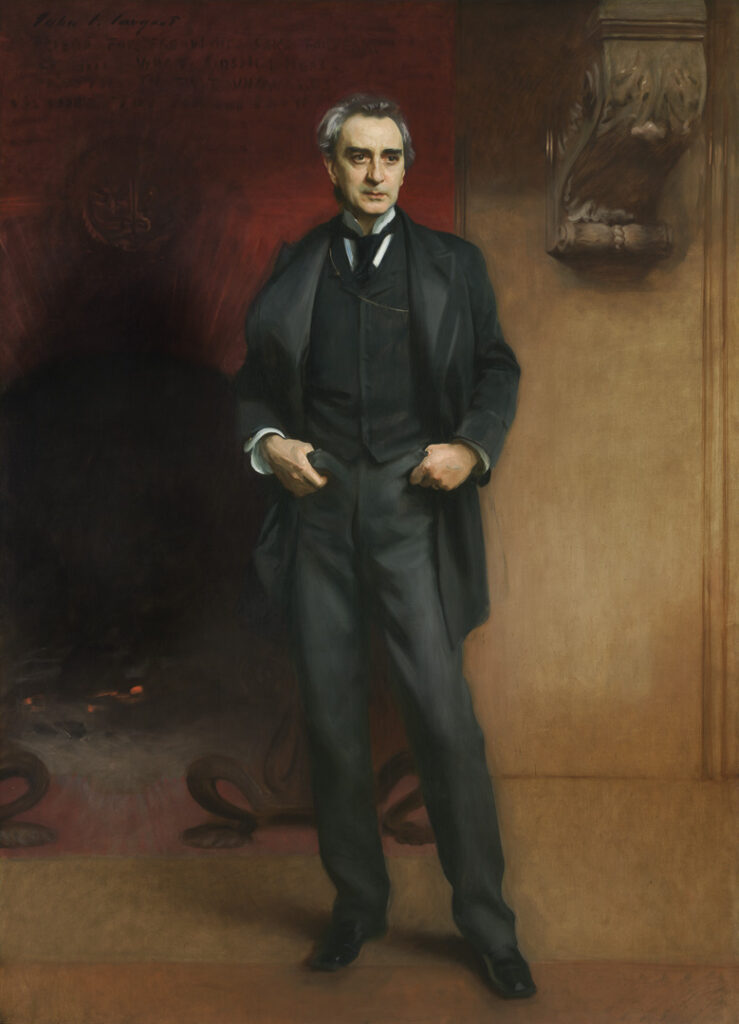

three years after Booth’s performance of Hamlet at the Grand Opera House in Peoria, Illinois. from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edwin_Booth#/media/

File:2013-7_s.jpg

Like many families of the era, loyalties were divided. Edwin was a staunch Unionist and supporter of abolition while John Wilkes fought aggressively for Southern secession. Having chosen the winning side in this struggle, despite the dastardly deed committed by his younger brother, Edwin continued to perform to broad acclaim for more than two decades following Lincoln’s death. And, given the silken nature of the playbill, I think we can at least count among the people of Peoria an audience full of those who did not hold Edwin accountable for the crime of his brother. (I am sure there is a lesson in this one, somewhere, but I am not sure exactly what it is. Luckily, I’ll have a reminder to what now evades me hanging on the wall.)

Adding a bit of mystique to the silk playbill I now possess is that Lincoln was assassinated while attending a performance of My American Cousin at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. Indeed, the two versions of the playbill distributed that fateful night are among the most coveted of collectibles. While the same cannot be said for the treasure my mother has provided, I recall admiring the curious memento as it was hung in my grandparents’ home long, long ago… so, for me, continuing to display it serves as a pleasant reminder of days-gone-by.

This is the potential power of artifact; an object that conjures memory and induces reminiscence offers a tactile connection to the past. And, in the case of my framed silk playbill, extra layers of reflection are inevitable as the name Booth jumps off the old fraying canvas.

There is a human tendency, exacerbated in my view while living in a fast-paced and unreflective society, that leaves us feeling tethered only to those things of the here-and-now. We have all had those moments when the hours of the day can sometimes slip away and only occasionally do we look back and wonder where all the months and years have gone. The result, I suggest, is that our history can sometimes fade into a foggy notion of black and white images seeming so old as to drift into irrelevance.

With this thought in mind, a few things occurred to me as I looked into the life of Edwin Booth; which I have concluded illustrates the fleeting nature of time and our oft-distorted sense it.

Edwin Booth lived long enough, and was famous enough, to have his voice recorded while performing Shakespeare’s Othello. So we can, in 2022, listen to the recorded voice of a man born only 57 years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence.**

Someone my mother’s age now at the time my mother was born would have been born herself in 1844 when Edwin Booth was 11 years-old.

If Edwin Booth had lived to age 100, he would have been able to vote for Franklin Delano Roosevelt who, as president, oversaw the development of the atomic bomb, ushering in the nuclear age and the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

And, speaking of the Soviet Union, if Edwin Booth had lived to be 100, he would have shared the planet for two years with a young Mikhail Gorbachev, who only recently passed away in August 2022 at the age of 91.***

In short, we are simply not as far removed from these events as we sometimes imagine.

As to the legacy of the Booth name, it seems to have been influenced by a bit of cosmic justice. While John Wilkes clearly murdered one of the greatest American presidents, older brother Edwin, in turn, once saved the life of Robert Todd Lincoln, Abe Lincoln’s son.****

I’ll leave it to you to explore, and ponder, that one.

*In one of many fascinating bits of trivia and coincidence surrounding Lincoln’s assassination, John Wilkes Booth had previously performed on stage at Ford’s Theater several months before he took Lincoln’s life there.

** https://archive.org/details/OthelloByEdwinBooth1890

***Mikhail Gorbachev was the last leader of the Soviet Union before it collapsed in 1991. He is largely seen as a hero to the West for opening up and liberalizing Russia and Eastern Europe, bringing an end to the Cold War (1945-1991).

****https://www.nytimes.com/1937/04/11/archives/robert-lincolns-life-saved-by-edwin-booth.html