Short term rentals have become a source of income for some property owners in the Santa Monica Mountains and a source of aggravation for others, leaving local governments scrambling to regulate this burgeoning new industry. Most short-term rentals are quiet affairs—a room in a house, or an airstream in a backyard, but everyone has heard the stories about rogue motels: that party in Malibu with the overcrowded balcony that collapsed seriously injuring nine people; the fire that spread from a certain short-term rental campsite in Tuna Canyon and, within minutes, spread perilously close to homes in the Saddle Peak community; the illicit Bay Area Halloween party that resulted in the shooting death of five people.

New regulations have already been put in place in Los Angeles City, and will be coming to Unincorporated Los Angeles County—including Topanga—soon, while neighboring communities like Malibu are still wrestling with the Coastal Commission to find some way to limit rogue motels while still providing visitor accommodations.

Online short term rental services may be a new phenomenon, but for more than 150 years, enterprising local residents have made a living hosting visitors in their homes and on their property.

The history of the American motel and campground is tied to the evolution of the automobile, but even before Southern California’s automotive revolution, landowners were already taking advantage of the new, mobile middle class to cater to vacationers.

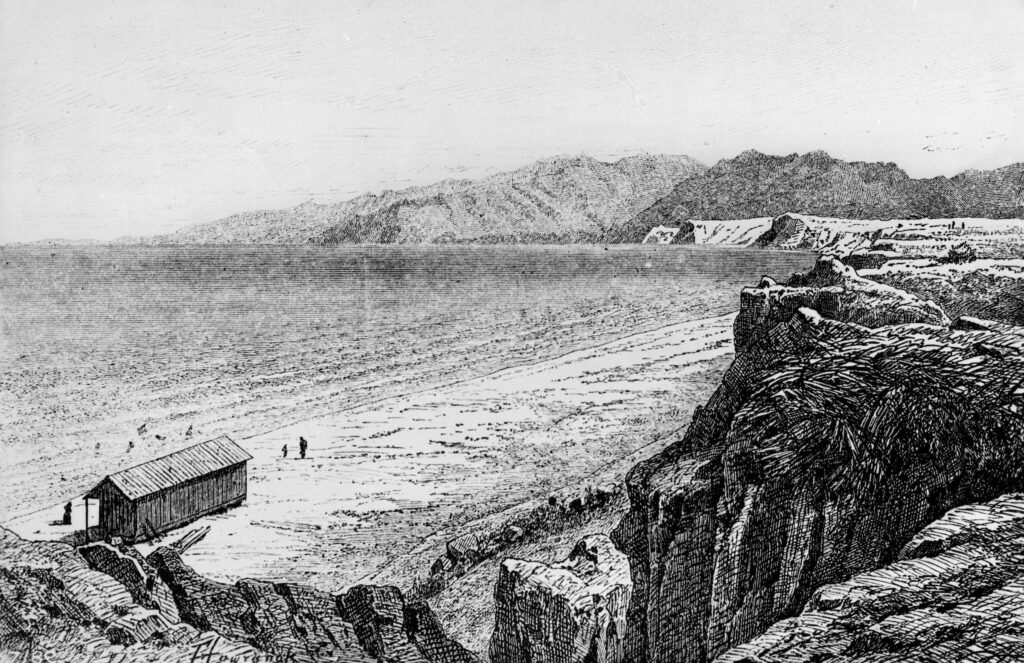

Late nineteenth century beachgoers had a luxury that has almost vanished today. Entrepreneurial property owners cobbled together cabins, beach shacks, bath houses, and tents right on the sand of the beach, from Santa Monica to Topanga.

In 1876, Michael Duffy built what is generally considered to have been Southern California’s first beachside bathhouse. It was located on Santa Monica’s North Beach, and had 16 rooms, each with a freshwater bath and shower. Modest Victorian beachgoers could change in privacy and exit their room directly onto the sand for comfort and that all important virtue, modesty.

The Marquez family, heirs to the original Mexican land grant that became the community of Pacific Palisades, were among the first to see the potential in tourism. Pascaul Marquez opened a bath house on the beach at Santa Monica Canyon in 1887, and built a campground overlooking the ocean. Within a generation, that campground was catering to the newly mobile class of Angeleno motorists.

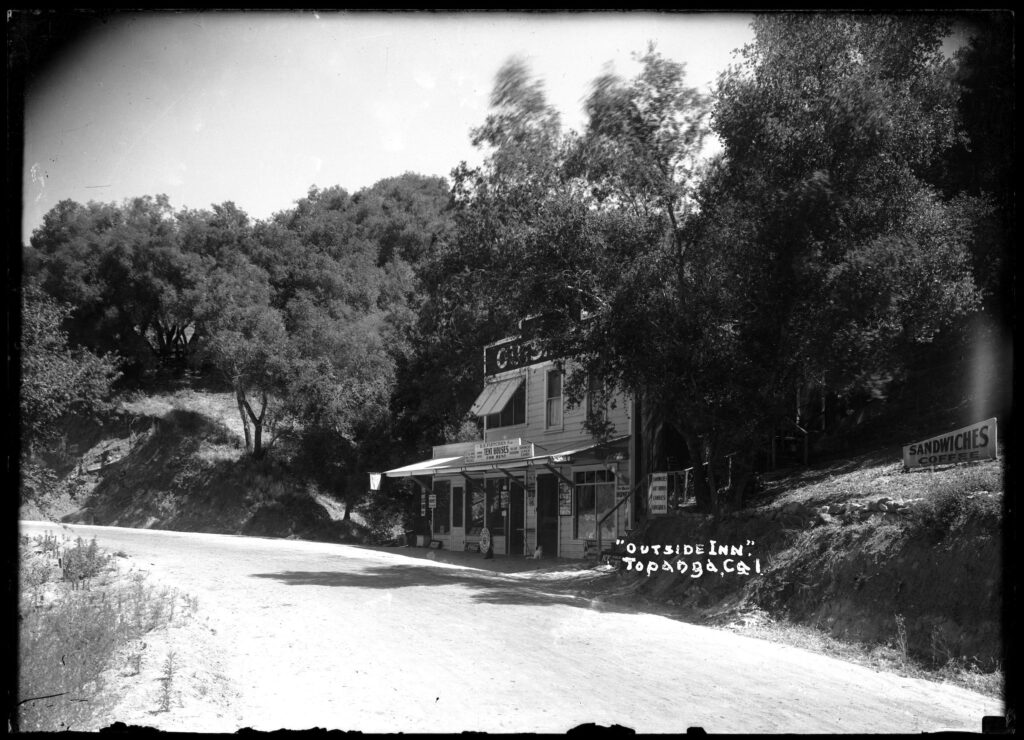

Stagecoaches carried the first generation of intrepid travelers to the Las Flores Inn on the edge of the off-limits Topanga Malibu Sequit Rancho, and up Topanga Canyon for a day trip, or to stay at a private campground that offered a taste of California rancho life, but they were spoon superseded by the automobile. In 1905, the Los Angeles Herald proclaimed Topanga Canyon the ideal motoring destination: “One of the most picturesque and best known mountain gorges to be found along the coast.” Motorists who read glowing descriptions like the one in The Herald were often unprepared for the realities of canyon roads—some things never change. They broke down, got stuck, and got lost. Enterprising homesteaders soon found they could augment their income by renting rooms or planting campgrounds amongst the bean fields and apple orchards.

McAlister’s Tavern was one of the first homegrown Topanga hostels. The tavern’s proprietor, Stella McAllister, turned her Cheney Road homestead into a boarding house in 1905, after the death of her husband. Stella was already locally well known as an excellent cook. She began offering home-cooked meals and tent cabin rentals. Guests were expected to help with the chores, and their host had a reputation for not suffering fools gladly, but her dinners were legendary, and the tavern was a local institution for more than a decade.

Other homegrown hostelries soon appeared. McAlister’s Tavern was soon joined by Camp Topanga in Old Canyon. This ill-fated resort opened in 1909 and was almost entirely swept away by record flooding in 1914.

The nearby Moel-y-Gan Mineral Springs fared somewhat better. A brochure advertises “Auto Stage Trips,” via “electric cars” from Santa Monica, $3 per passenger, including “a dinner fit for a king!” The advertisement enthuses about the health-giving mineral spring, views that “resemble those of the Grand Canyon,” and that there were “no mosquitos or vermin.”

The resort reportedly closed precipitously after the proprietor, George Pickett, eloped with a guest.

The number of camps and resorts continued to grow throughout the early years of the century. They ranged from Kneen’s Camp, built in 1916 by stonemason Thomas William Kneen, to Cooper’s Camp, a ramshackle collection of tents and cabins by the side of the Topanga Lagoon. Visitors were entertained with fishing trips, nature walks, and 1920s jazz era dance bands.

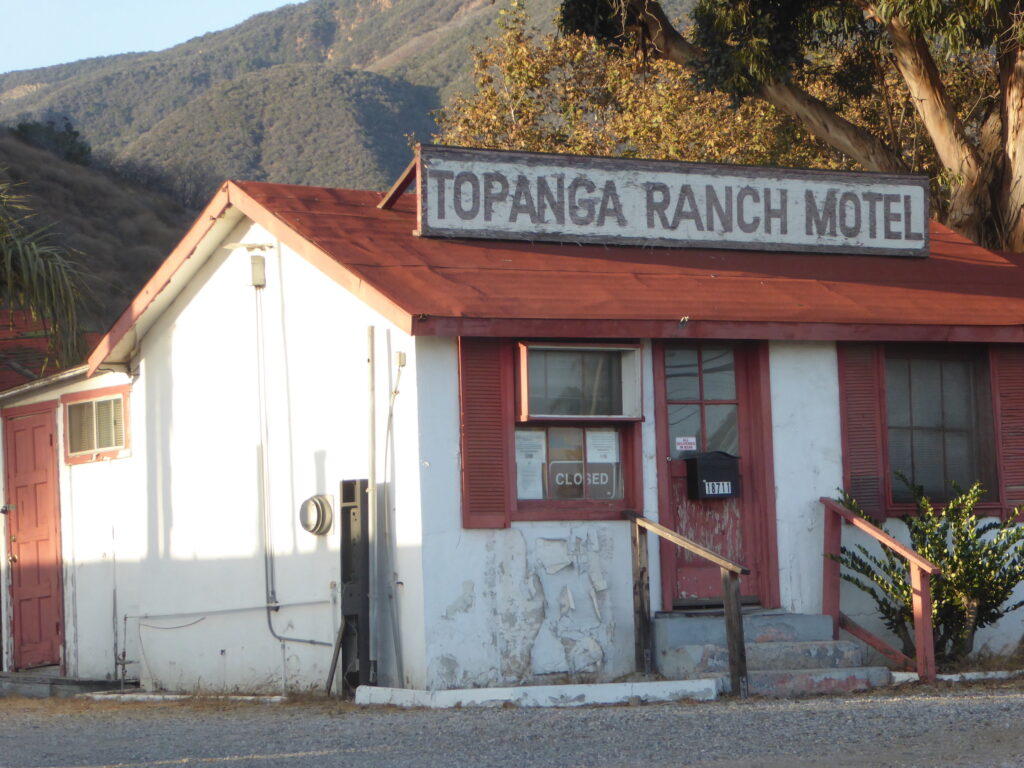

A new concept arrived in the 1930s, the motel. The name is a portmanteau word made out of motor + hotel. They sprang up all over, but in the early years, they were usually family owned. The Topanga Ranch Motel, built in the 1930s, was one of the first local hostelries to cater exclusively to the motorcar crowd. It grew out of the tents at Cooper’s Camp.

Carl’s Motel—better known as the Sunspot—was another of the first motels in the area. This 12-room motel, just east of West Channel Road, exemplified the motor hotel ideal. Completed in 1938, it was designed by well-known Los Angeles architects Alexander Schutt and A. Quincy Jones.

Despite its decline and ignoble end as a dismal disco dive and house of ill repute in the 1970s, Carl’s Motel, designed to offer food, accommodation, and gas, was a landmark. In his application to the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Commission to get the building listed as a historic landmark, preservationist Bradley Weidmaier described the motel as “a brilliantly orchestrated complex.” Unfortunately, this motel’s architectural significance wasn’t enough to save it.

The Riviera Motel at Point Dume was one of the first. It was AAA-approved and spectacularly pink inside and out—First Lady Mamie Eisenhower’s favorite color. For a weary motorist arriving at the Malibu Riviera Motel after a drive along the mostly uninhabited Malibu coast, it must have felt like being transported to the Technicolor Land of Oz.

There were others, but today it requires a bit of detective work to find them. The Las Tunas Isle Motor Hotel advertised in the Malibu Times for a couple of years in the late 1940s before turning into an apartment house. It’s the apartment complex with the Tiki masks in front of it near Topanga State Beach. It once boasted a swimming pool right by the ocean, a novel concept in the 1950s. The Ocean View Hotel is the building with the wonderful 1940s curved corners that is still on PCH near Carbon Beach. The quaint shops at the Malibu Country Mart were once motel rooms. The popular playground in the middle of the center was the motel pool.

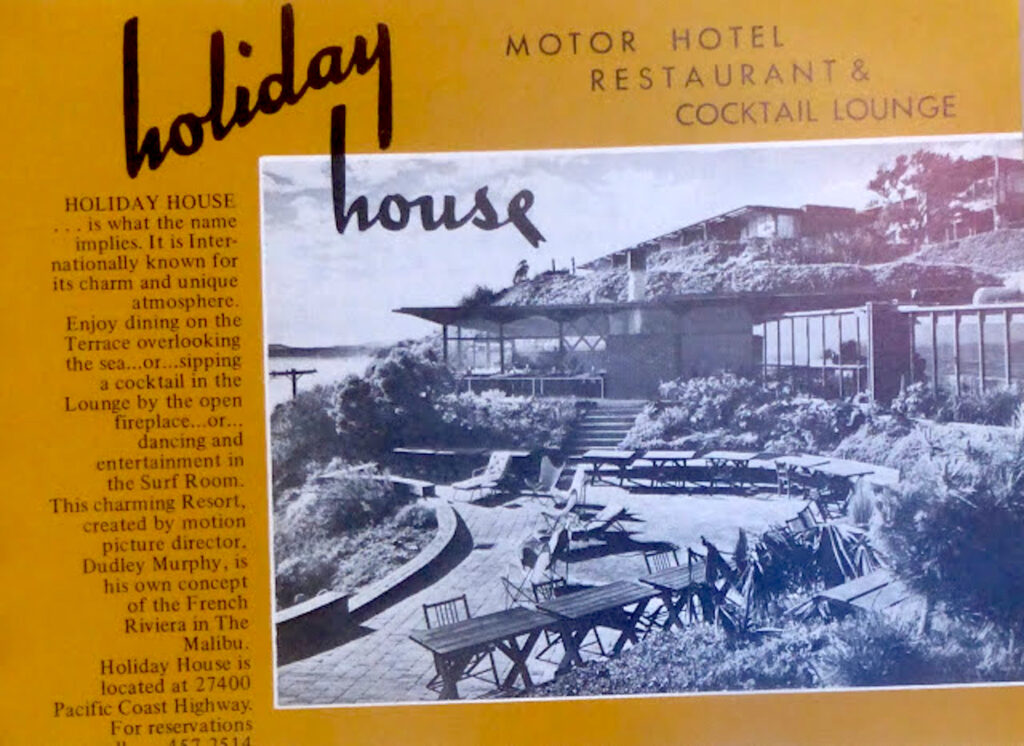

Visitors can still enjoy dinner on the terrace at the site of the old Holiday House (now Geoffrey’s Restaurant), built in 1956 by silent film director turned entrepreneur Dudley Murphy, but the Mid-Century architecture designed by Richard Neutra has been dimmed and diluted by later remodels, and there are no longer accommodations there.

Easily the most colorful Malibu motel was the legendary Tonga Lei, which opened in 1961 on the site of the earlier Drift Inn. Tonga Lei’s Polynesian-themed restaurant and bar are remembered for the tropical cocktails, flaming torches, and genuine carved Tiki gods, but the small motel—it only had nine rooms—attached to the restaurant was also a temple of Tiki decor, resplendent with bamboo furniture, wallpaper made out of old Asian newspapers, and an entire pantheon of Tiki idols. It was replaced in 1987 with a three-story, 47-room hotel, touted in an L.A. Times article as “the first new hotel in Malibu in 37 years.”

Almost nothing remains of the ill-fated Albatross Motel. This motel, located next to the former site of the Las Flores Inn, began life in the late 1940s as the Malibu Movie Colony Motel. It had a colorful, and sometimes off-color reputation for romantic assignations and illicit activities that are difficult now to substantiate. The site is reputed to be haunted—another claim that is difficult to prove. There isn’t much left for the ghosts. The motel burned down in 1963, and was never rebuilt. All that is left are a few pylons.

The Tonga Lei and the Albatross summarize the trajectory of the American motel—from modern convenience to urban decay, and from there, either to gentrification and luxury upscaling, or to oblivion.

No one cared much about the Great Motel Extinction of the 1980s and ’90s. It was a gradual phenomenon, more like the end of an ice age than the sudden change precipitated by an asteroid, but rising real estate prices have been just as fatal to local guest services in their own small way as the arrival of the asteroid Chicxulub was to the dinosaurs.

During the declining years, motels offered inexpensive accommodations for summer employees and struggling writers. We know a screenwriter who would stay at the Topanga Ranch Motel for weeks in winter. Once a glamorous example of bungalow-style California architecture owned by William Randolph Hearst, it was now a gently decaying relic, but it was cheap, and quiet, and there were no distractions—just a TV that only received three stations on a good day, but by then, the era of the motel was over.

Now, when independent motels with their boomerang-patterned formica, heated pools, and signs proclaiming “AAA Approved!” and “Vacancy!” have almost entirely gone extinct, taking with them the concept of affordable overnight accommodations, we are back to homegrown accommodations in people’s houses or backyards.

Author and journalist James Lileks collects, analyzes and pokes fun at motel ephemera. He writes, “Nostalgia for old motels, like most forms of nostalgia, is selective and dishonest. We like to imagine a pure world before the soulless hotel chains took over, a landscape of lovely neon, local charm, and individuality. No doubt this was the case… but it was only part of the story.”In a way, it’s a story that is still being written. The county’s short term rental ordinance may change the way the current business model works, but travelers will always be drawn to the coast and the canyons, and they will always need a place to stay—quiet, comfortable, preferably not too expensive, and someday, perhaps, a nostalgic memory of a golden holiday in the vanished past.

I didn’t grab the last copy of this issue from cafe marmalade because I assumed I’d get one from the PO; and when I got there, there weren’t any. Chances y’all have a paper copy of this issue? I’d love to have one. Thanks

If you are in Topanga you can pick up a print copy at our offices. If you let us know when you’re coming we’ll be sure to put some outside the door in case you miss us. [email protected]

[…] from an excellent piece in Topanga New Times, dated 11.4.22 and titled “Hotel California.” Written by Suzanne […]

Beautiful beach. Paradise Cove