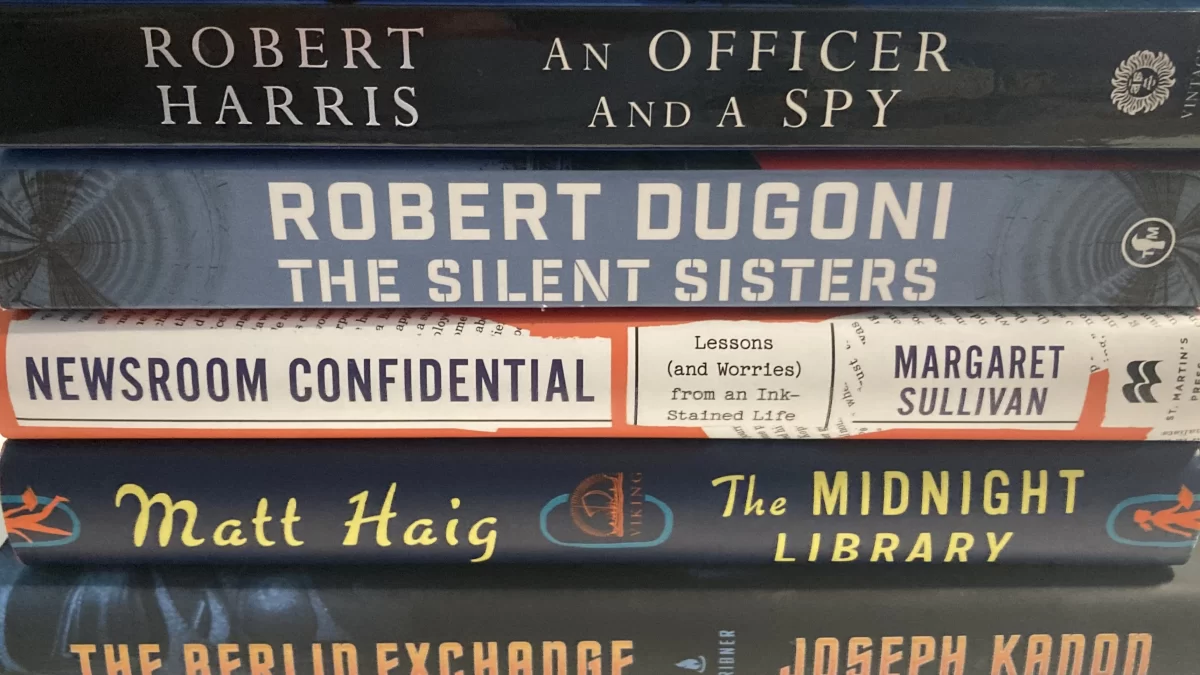

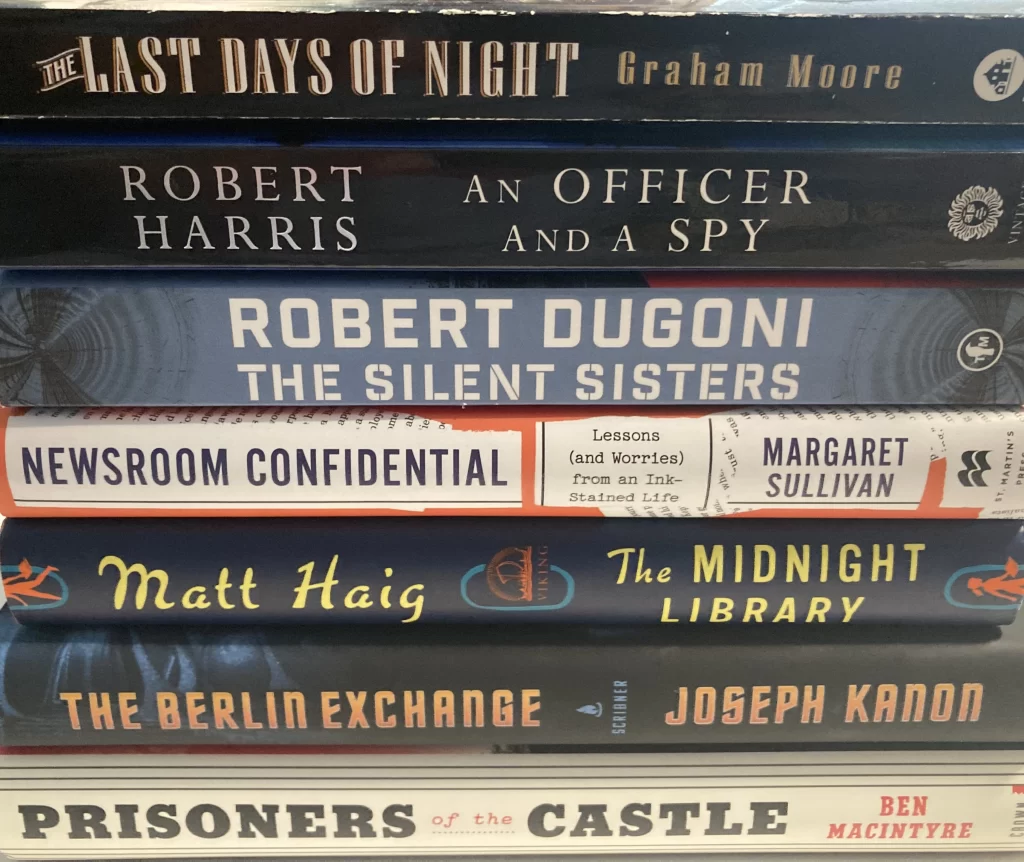

If there must be a theme for this collection of books, it can be said for certain that I loved and appreciated and now share with you each and every one of them So, here are four histories, three of them fictionalized; a fantastical tale of a very special library; a journalist’s memoir; and two book series which feature all that is good in leisurely fiction.

Set primarily in New York City during the industrializing year of 1888, The Last Days of Night (2016) by Graham Moore revolves around the contentious competition between Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse as they tangled over the future of electric light and, in turn, the nature of our electrified world today. Westinghouse supported the long-distance efficiencies of alternating current (AC) while Edison claimed that direct current (DC) is much safer; at one point encouraging the development of the electric chair to prove that AC can kill. Along the way, an elephant and other smaller animals are used in a series of ghastly displays to discredit Westinghouse.

While the unfolding technology examined in Moore’s fine book is fascinating, The Last Days of Night is also an exciting legal thriller as Edison and Westinghouse engage in all sorts of shenanigans to outsmart the other. Edison, in particular, is portrayed as a dubious character and one is left wondering why it is today, the famous inventor is held in such high esteem.

While admittedly dramatizing these events, Moore’s historical fiction effectively grasps the mood of late nineteenth century New York as the city is for the first time illuminated with electricity. The obsessive Nikola Tesla’s portrayal hints at the idea that true genius and social grace are often at odds with one another, perhaps offering some insight into the twenty-first century’s Elon Musk and his affection for the polymathic Serbian-American. My namesake, the filthy rich banker J.P. Morgan, appears in The Last Days of Night and reminds us that advances in science and technology are beholden to those with capital.

A film from 2017, The Current War, also explores the Edison-Westinghouse debate although, despite its star-power, it was met with poor reviews. Perhaps the producers should have engaged the assistance of Mr. Moore with his flair for drama and intrigue because The Last Days of Night is a really good read.

Also set during the late nineteenth century—this time in France—is An Officer and a Spy (2013) by Robert Harris. The story opens with the public degradation of Captain Alfred Dreyfus and his imprisonment on Devil’s Island off the coast of South America; after his conviction for delivering French military secrets to Germany (the tension that existed between the two countries at the time would reach a violent crescendo in the muddy trenches of World War I less than 20 years later). Unfortunately for Captain Dreyfus, his guilt seems to have been crafted due to his Judaism rather than any authentic examination of the facts.

While we often associate anti-Semitism with Nazi Germany and the Holocaust, the horror of those events tends to obscure the fact that anti-Jewish sentiment has expressed itself throughout history and in many different forms. In 1890s France during The Dreyfus Affair, as it has come to be known, we see in Harris’ extraordinary telling the virulent strain of anti-Semitism, expressed with hate-filled and public pronouncements, that would, less than 50 years later, make the Holocaust possible.

The unlikely hero of Harris’ riveting account—our officer and spy—is the ambitious Colonel Georges Picquart, who reluctantly becomes the head of the French army’s counter-espionage agency. After discovering that another French officer continues to provide information to the Germans after Dreyfus is locked away in a hellish nightmare on Devil’s Island, Picquart eventually discovers corruption at the highest levels of the French military and government.

Before investigating further, I assumed while reading that Picquart was Harris’ invented tool to dramatize his historical fiction; nope, Colonel Georges Picquart actually lived and breathed the Dreyfus Affair. In an interview promoting his book, Harris calls Colonel Picquart the “first great whistleblower” who sacrifices all to expose “perhaps the greatest political scandal and miscarriage of justice in history, which in the 1890s came to obsess France and ultimately the entire world.”*

While admitting to taking only a few liberties with the historical record, primarily by assigning personality traits to the main characters, Harris sticks to the heart of the matter; Picquart’s steadfast effort to face down institutional corruption because it is the right thing to do, no matter the individual consequences. There is a lesson for us here as the institutions of power in our own world seem darkly susceptible to the same set of corruption and bigotry that plagued 1890s France.

Unlike Graham Moore and Robert Harris, who rely on small doses of fiction to tell largely true stories, acclaimed World War II and Cold War historian Ben Macintyre is the real deal. His latest is Prisoners of the Castle: An Epic Story of Survival and Escape from Colditz, the Nazis’ Fortress Prison (2022). Set during World War II, Macintyre adds to his long collection of previously untold histories in thoroughly researched and dramatic style. In this case, Colditz, a Gothic castle overlooking the sleepy village of Colditz near Leipzig in central Germany, is the incarceration space of last resort for Allied prisoners of war – primarily British, Polish, French, and Dutch—who have demonstrated an uncontrollable determination to escape. Following the Allied invasion of Italy and the D-Day invasion at Normandy in France, American POWs began arriving, as well.

Defying the horrors swirling around them during the bloodiest decade in human history, the relationship between the Germans running the prison and Allied captives is remarkably cordial. This is made possible as the German commandant is no great fan of Adolf Hitler and certainly no Nazi. On the contrary, he is an officer and a gentleman and, despite the situation, he treats the Allied officer/prisoners in his care with full deference to the newly-minted Geneva Conventions, which prescribes the honorable manner in which prisoners of war must be treated. Indeed, one of the primary characters in Macintyre’s work is a Swiss official who periodically visits Colditz with the purpose of confirming their proper treatment.

While reading, I was reminded of Hogan’s Heroes, a 1960s TV sitcom set in a German prisoner of war camp, Stalag 13. While the motley collection of Allied prisoners on the TV show engaged in sabotage missions as they hilariously leave and enter the camp at will, the prisoners at Colditz were obsessed with escaping and their elaborate plots demonstrated the lengths they were willing to go to get out. Although, on several occasions, Colditz prisoners were allowed special privileges, including leaving the prison itself; but only if they promised not to attempt an escape, an agreement known as a parley. “Not once,” Macintyre writes of the honor between enemies, “did a prisoner give such a guarantee and then break his word.”

The prisoners of the sitcom and those at Colditz both used disguises including German uniforms and cardboard cutout “guns.” And, much as it is portrayed in Hogan’s Heroes, Colditz prisoners gained the support of friendly Germans in the nearby town. Eventually, however, the story of Colditz becomes no laughing matter. The Germans became pathologically desperate as the war wound down. Macintyre weaves this tale and its shifting emotional landscape with great skill and he illustrates his enthralling book with a collection of stunning photographs that bring this history to life.

Amazingly, much of the gadgetry used by escape-minded prisoners was collected by the German commandant and is now on display in a small museum in Colditz. The prisoners smuggled in radio parts to communicate with London, currency to bribe the guards, and also built a glider, as Macintyre describes it, “in absolute secrecy from floorboards, bedposts, and mattress covers, an astonishing feat of aeronautical engineering.” In a lone photograph of the “Colditz Cock” – named for a bird that does not fly – the machine is poised as if staring out of the top-floor windows of Colditz, contemplating a flight…”**

I heartily recommend this one and all of Ben Macintyre’s work; several volumes of which I previously reviewed in this space.***

Another favorite author of mine, Joseph Kanon, has recently released The Berlin Exchange (2022). Unlike the other historical fiction referred to here, where real-life characters are embellished, Kanon introduces entirely fictional primary characters who live through accurately portrayed historical events. It is Berlin in 1963, on the rather unpleasant side of The Wall. An East German spy, physicist Martin Keller, who helped steal America’s secrets during the development of the atom bomb, is swapped back into East Germany where he is received as an ostensible hero. Having been imprisoned several years in Great Britain for espionage, Keller discovers that upon arriving in East Berlin, he has simply replaced one prison for another. The socialist workers “paradise” of East Germany has devolved into a police state.

Keller’s guilt over his role as a spy haunts him as he tries to make amends. Adding to the intrigue is a divorced wife who was once Keller’s partner in espionage, their son and her new husband, an East German intelligence official in charge of arranging the prisoner swap that brings Keller “home.” Good complicated and sinister stuff, this one.

Finally stepping away from the history department, here are a few other books I have enjoyed recently.

Visiting Matt Haig’s The Midnight Library (2020) offers the opportunity to redo one’s life, each of the thousands of books on the shelves is a version of how it could have turned out. Of course, anyone who dares select a book off the shelf is inevitably remorseful or regretful and makes the selection to correct the shortcoming. The dizzying array of consequences makes this one a delightful reflection on the ups and downs of a human life; and eventually, learning to manage the hand we’re dealt with grace.

Newsroom Confidential: Lessons (and Worries) from an Ink-Stained Life (2022) by Margaret Sullivan is a revealing look into the transformation of print journalism over the last four decades through the eyes of one of its pioneering women. Rising to national prominence in 2012 as the first female public editor at The New York Times, Sullivan set a new standard that challenged the famous institution’s ability to seriously question its own practices. In 2016, she joined The Washington Post as its media columnist at a time when news outlets struggled to keep their cool in The Age of Trump.

I am also enjoying the fiction of Robert Dugoni whose Charley Jenkins series follows the former CIA officer who becomes the perfect candidate to uncover the Russian operative who is knocking off American clandestine assets known as the seven sisters. Another Dugoni creation, Seattle Police Department Detective Tracy Crosswhite—in each of the first three of 10 anyway—carries out her official duties as a murder investigator while simultaneously resurrecting cold cases from Washington’s past; including the murder of her own sister, 20 years earlier.

Please let me know if any of these wonderful books makes its way onto your nightstand. Happy Dayz!

*Interview with Robert Harris

**Visit Colditz Castle in Germany

https://www.schloss-colditz.de/en/home/

***Links to Books & Such, Spy Games and Spy Games II