In the early twentieth century, nearly one quarter of the earth’s land mass and nearly one quarter of the world’s human population was, in one way or another, under the dominion of the British Empire. Building the largest power the world had ever known meant controlling the narrative; shaping the stories that elevate the virtue of the empire while justifying the conquest of others. Sometimes this is not so easy to do, as the following illustrates.

In the 1740s, during The War of Jenkins’ Ear, a British squadron made up of eight wooden sailing ships including five men-of-war set sail in pursuit of a treasure-filled Spanish galleon known as “the prize of all the oceans.”

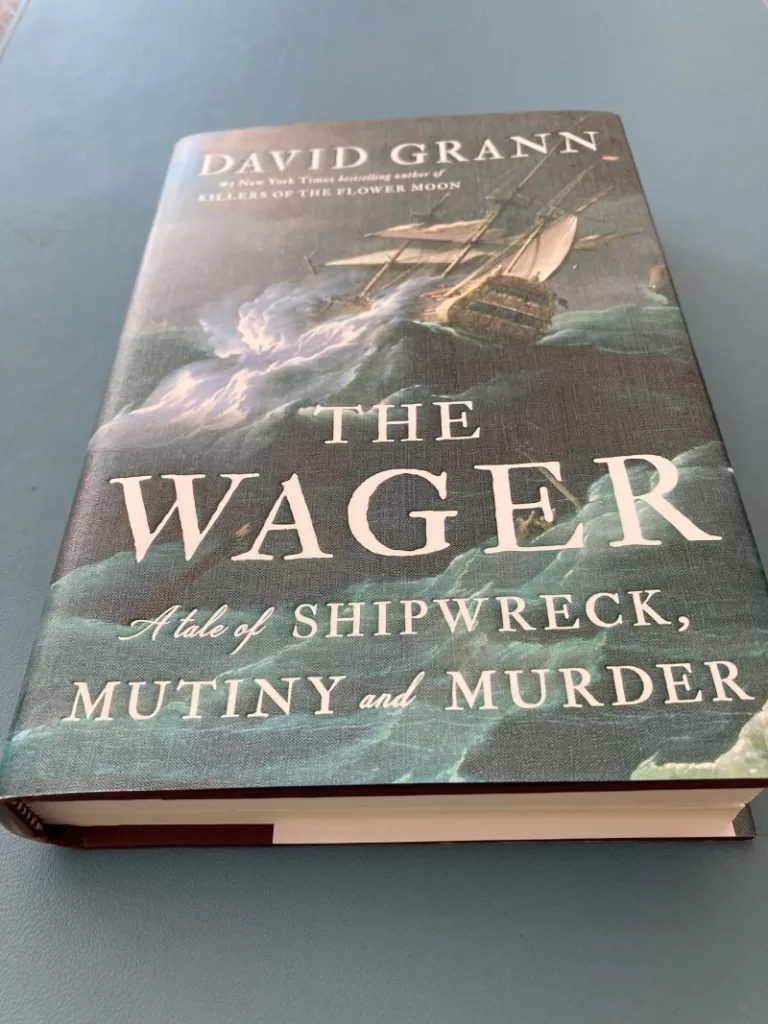

The fate of one of these ships is examined in The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder (2023) by David Grann; a fascinating and entertaining account of a disastrous and tragic episode in British Empire history.

With a contingent of some 2000 men and boys, the squadron’s mission was to cross the Atlantic, round Cape Horn, and then commence “’taking, sinking, burning, or otherwise destroying’ enemy ships and weakening Spanish holdings from the Pacific coast of South America to the Philippines.” Setting sail on August 23, 1740 with a great deal of pomp and circumstance, unfavorable winds prevented their departure. In a dark omen to what lay ahead, it took more than three-and-a-half weeks to finally sail out of the English Channel.

The misery began almost immediately. Lice spread throughout the crew. A tiny bite left behind saliva that caused itching, which released bacteria found in traces of louse feces. The bacteria entered the bloodstream and caused typhus. “By December,” Grann writes, “more than sixty-five members of the squadron had been buried at sea.”

By the end of the month, a familiar island off the coast of South America was spotted. Hundreds of sick and dying seamen were carted ashore where “at least eighty men and boys died… their bodies buried in shallow sandy graves.” One hundred sixty of 2000 had perished while crossing the Atlantic Ocean. These numbers did not bode well on a mission designed to circumnavigate the globe.

By March of 1741, as the squadron approached Cape Horn, another illness ravaged the crew. Whereas typhus revealed itself with vomiting, diarrhea, and flu-like symptoms, scurvy wreaks havoc; bloodshot eyes bulged, teeth and hair fell out and, as Grann dismally reports, “[t]he cartilage that glued together their bodies seemed to be loosening.” One medical “expert” reported that some of the men suffered from “shiverings, tremblings, and… the most dreadful terrors.” Another observed that “the disease ‘got into their brains, and they ran raving mad.’”

(Known as “the plague of the sea,” scurvy “was the great enigma of the Age of Sail, killing more mariners than all other threats—including gun battles, tempests, wrecks, and other diseases—combined.” A few crates of limes could have saved them all.)

By the time the squadron reached Cape Horn and the seas began to churn, “nearly 300 of the [flagship] Centurion’s some 500 men were eventually listed as ‘DD’ – Discharged Dead. Of the roughly 400 people on the Gloucester [another man-of-war] that had departed from England, three-quarters were reported to have been buried at sea…” Grann adds that “there were so many corpses, and so few hands to assist, that the bodies had to be heaved overboard unceremoniously.” Many of the suffering survivors “envied those whose good fortune it was to die first.” (This is not the story of empire.)

And our story is just beginning.

While attempting to round Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America during a ferocious storm, HMS Wager, captained by David Cheap, became separated from the rest of the squadron and then was cast upon a rocky shore in Patagonia in what is now southern Chile.

Of roughly 250 Wager crew members who sailed out of the English Channel on September 18, 1740, 140 souls reached what would become Wager Island. Isolated in the vast archipelago of Tierra del Fuego, it quickly became evident to the shipwrecked survivors—whose numbers were dwindling—that rescue was unlikely, if not impossible.

Already ravaged by disease and washed ashore in an extremely harsh environment, the outlook was grim. “Faced with starvation and freezing temperatures,” Grann writes, “they built an outpost and tried to recreate naval order.” Captain Cheap exerted his authority while a growing number of crewmen began to argue that their predicament and the loss of the ship meant they were no longer bound by rank. (This is not the story of empire.)

Cheap knew trouble was brewing among his men when the ship’s carpenter John Cummins publicly told him, “Sir, ‘tis all owing to you that we are here.”

Cheap’s efforts to maintain order and exercise authority broke down as he insisted that any effort to leave the island must be done in support of their original mission; heading north along the Chilean coast. His idea was to capture a Spanish ship and then find the rest of the British squadron. While Cheap’s loyalty and patriotism can be seen as admirable, the dire circumstances led others on the island to question the captain’s sanity.

At one point, Captain Cheap is reported to have shot and killed a belligerent and unarmed crewman. In response, the charismatic John Bulkeley—the ship’s gunner—rallied most of the crew to challenge the captain and do all they could to make it home by heading back to the Atlantic. Adding to their physical privations were a growing number of suspicious behaviors, including the theft of weapons and the small amounts of food they had; seaweed, wild celery, and spoiled meat, flour, and peas salvaged from the Wager.

“Although the dispute centered on a simple matter of which way to go,” Grann writes of the increasing tense and fraught interaction among the castaways, “it raised profound questions about the nature of leadership, loyalty, betrayal, courage, and patriotism.”

Among people claiming the right to “civilize” much of the rest of the world, the events of Wager Island do little to promote their cause. “[A]s their situation deteriorated,” Grann writes, “the Wager’s officers and crew—those supposed apostles of the Enlightenment—descended into a Hobbesian state of depravity. There were warring factions and marauders and abandonments and murders. A few of the men succumbed to cannibalism.” (This is not the story of empire.)

If the Wager had been lost at sea, or had the shipwrecked survivors simply perished as it seemed so likely they would, there would be no story except that crafted by British myth makers. As it turns out, the story of the Wager would be told by eyewitnesses. Unfortunately for the truth, these “eyewitnesses” offered wildly contradictory accounts of their adventure. And they did so for incredibly obvious reasons; not the least of which was the looming threat of a hangman’s noose.

In the end, the official record grasped onto a relatively minor accomplishment of the disastrous mission and over-celebrated its significance in order to cover up the ugly things that actually happened. This, after all, is what empires do. “Empires preserve their power with the stories they tell,” Grann writes, “but just as critical are the stories they don’t—the dark silences they impose, the pages they tear out.”

Thanks to David Grann and his brilliant history writing, some of those dark silences have now been cast in the light of day and some of those pages have been re-inserted. Even then, we still come up a bit short if our goal is to know for certain how it all played out. The best we can hope for then, in many instances, is to be reminded now and again—as Grann’s book does—that empires, nations, and people for that matter, craft a narrative that suits their needs… no small lesson in these dis-informative times.

*I listened to the audiobook of this one first and then read the book. I then listened to several passages again. As with movies, I have determined that reading the book first is the way to go. The first listening was a passive experience—as explored in this recent Atlantic article.

https://www.theatlantic.com/books/archive/2023/06/audiobook-format-history-reading-criticism/674460/

The second listening was an absolute delight.

As always, an excellent and interesting review.

Well, thanks BG, I’m glad you enjoyed it.