I like to refer to myself as a World War II scholar, a label my husband reminds me might more appropriately be termed ‘buff’. My father was born on D-Day, the 1944 invasion of Normandy, France that marked the Allies’ advancement and the turn of the tide for control of the region. The nurses who should have been assisting my grandmother with her labor and delivery were huddled around a radio, anxiously awaiting news from the front.

My maternal grandfather was a tank commander and later sergeant in the Battle of the Bulge, another turning point of the war in Europe.

An interest in WWII is in my blood. So I was heartened to learn of a spry vet living in my neighborhood, hopeful I could put his story, or at least a humble part of it, into print. A week after my discovery, we were sitting down in his Topanga home for a long chat.

William (Bill) “Skip” Dillon was born near Pittsburgh, PA in 1924. He is nearly 99 years old, but you wouldn’t know it to speak with him. He is quick-witted with a warm smile, making it easy to connect. “You have to remember,” he tells me, “I was a child of the Great Depression. There was no bacon, no sugar, no eggs, no jobs to be had. When I gave my father the papers that would give his permission (to go into the Navy), he just asked where to sign. I was just another mouth to feed, you see.”

Families with scarce resources often felt their children would be better taken care of by the US government. They would have food, pay, and—if they took advantage of the GI bill, as Bill later did—an education. When asked about the temperament of WWII soldiers, Bill said, “the Depression gave us discipline and taught us how to get along; it’s what made us the people we were.”

Remembering is something Bill is well suited to. “My memory is as clear today as when I enlisted at 17 years old,” he tells me, continuing, “but if you’ve got a question to ask, you better ask it now.”

I imagine this joking attitude toward one’s own mortality is something ingrained in all soldiers. I asked Bill my most pressing question, the one that despite all the books I have read has not been answered: how did he come to terms with all the death around him, and with the knowledge that he was not just saving lives, he was taking them? His response was simple: overwhelming patriotism. “We never gave it a thought, because we never saw the men we killed,” he said.

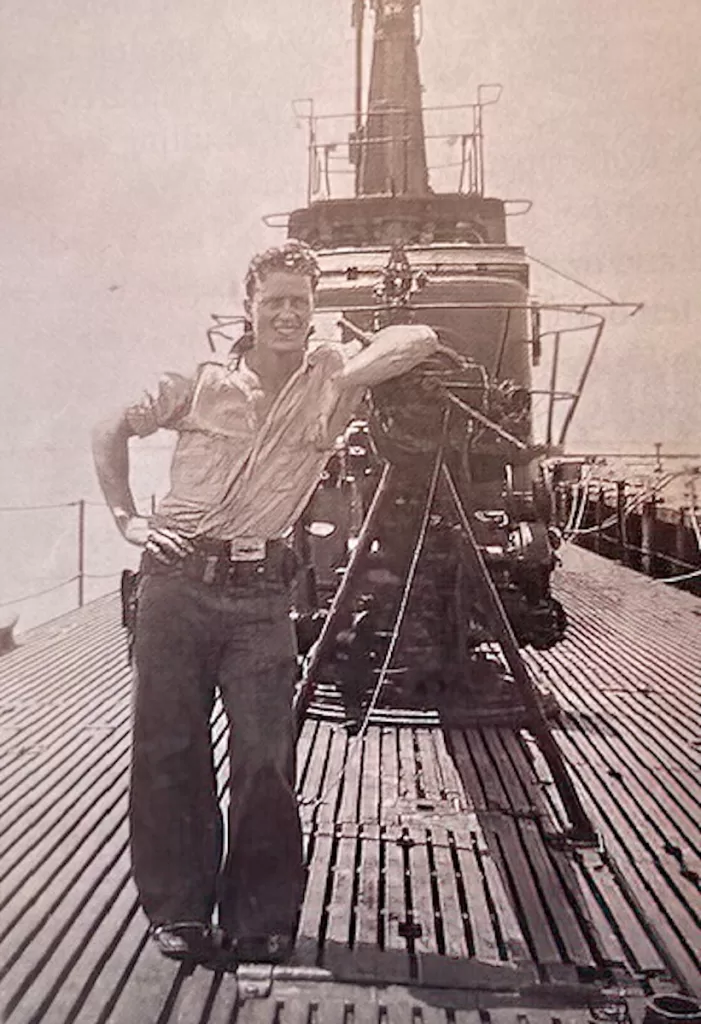

Bill was a submariner on the USS Sailfish, radioman first class in the Pacific Theater. As such, he and fellow submariners often wouldn’t know if a fired missile hit its target until days later. They relied heavily on radar, a new technology at the time that the Japanese didn’t yet have. They had to compartmentalize to do their job. With each enemy vessel sunk, Bill and his comrades toasted each other, feeling they had done their part to bring the war to an end and restore peace.

Unlike conflicts that would follow, WWII was unique in that there was never a question as to why we were fighting. There was never a concern about the appropriateness of US troops on foreign soil. The only question was whether or not our boys would return home safely. Getting home in one piece was the motivating factor for Bill to volunteer for submarine duty. He informed me that you could not be drafted onto a sub, and even those who were on board voluntarily had to be reassigned should they request it. There was a lot of seasickness as men acclimated to two months at a time on a sea-faring vessel. Life on a WWII submarine was different from infantry work in other ways as well. There were no opportunities to make phone calls or send letters home because there was no ‘leave’. The sub only came to land if it ran out of fuel, food, or ammunition.

Bill stuck it out, as he felt his chances of survival were greater at sea than in active combat. In his four year tenure aboard the Sailfish, he and his crewmates sunk or damaged 21 Japanese ships, and rescued 12 American pilots that had been shot down during the battle of Formosa.

Some of his exploits are so gripping they are the subject of a book by Stephen L. Moore, Strike of the Sailfish: Two Sister Submarines and the Sinking of a Japanese Aircraft Carrier. It will be available in December, but can be pre-ordered now on Amazon.

The book description reads, “In 1939 off the New England coast, the submarine USS Squalus is accidentally sunk during a training exercise, killing half her crew. Coming to the rescue is the USS Sculpin, in many ways the Squalus’s twin. The remaining crew aboard the Squalus are saved in a lengthy, white-knuckle operation, and eventually the sunken submarine is raised, repaired, and returned to duty, with a new name: the Sailfish.

Four years later, on patrol during the darkest days of the Pacific War, the Sailfish’s radarman picks up the tell-tale signs of a Japanese aircraft carrier, the greatest of all enemy ships. Never before has an American submarine taken down a carrier (by themselves, without backup). Immediately, the crewmen swing into action, embarking on a deadly game of cat-and-mouse as this once-dead boat evades enemy cruisers to stalk closer and closer to their prized target. Little do they know that aboard the Japanese carrier are the sole survivors of an attack on the USS Sculpin, the very boat that saved the Squalus-turned-Sailfish back in ’39.”

Bill Dillon collaborated with the author to tell the harrowing story. Today, he is the sole survivor of the 200 men he served with on the Sailfish, and the last American survivor of the battle of Formosa.

Editors note: In 2003, Bill Dillon participated in a lengthy oral history interview for the National Museum of the Pacific War, full of details of daily life aboard the submarine, Sailfish. https://digitalarchive.pacificwarmuseum.org/digital/collection/p16769coll1/id/4679/rec/2

One might presume that with so much adrenaline, intrigue, adventure, and camaraderie, Bill’s WWII years were his glory days. Yet he says his work after the war is what he is most proud of.

“During the war,” he recounts, “I was killing people. After the war I began to help people.”

He returned home to his fiancé, Janet, whom he married in January 1946. The couple went on to have seven children, but first, Bill needed to complete his high school education. He got his GED before earning an associates degree, and then a bachelor of science in electrical engineering and masters degree in systems management from the University of Florida. He began a PhD program at UCLA but ultimately decided to put his attention back on his family. In his new career, Bill helped to develop the first GPS system; he was instrumental in launching the United States’ first space satellite, and published five secret documents on satellite systems. In addition to his many war-time combat medals and commendations—including two bronze stars, one with valor—he was given special recognition by the consolidated space operations center, his one time employer. The latter is a framed certificate of merit for Bill’s part in building, at the time, the most advanced satellite control facility in the world.

Bill is also a member of the veterans associations American Legion and Wings over Wendy’s. He is close with his children and grandchildren, and is known by many in his Topanga community. He was Hero of the Game for the NFL Rams last year, as well as the LA Kings, and was honored by the Dodgers with the privilege of throwing the first pitch this past spring. Bill has been further honored by the Reagan Library, and last December appeared on CBS News, KCAL 9. All this sudden attention seems to have taken Bill by surprise and isn’t necessarily what he would seek, yet he realizes his unique position. “I’m a living history book,” he quips.

Bill Dillon has happily lived here in the Santa Monica Mountains for 53 years. He was one of the original 19 families to settle the Viewridge neighborhood, and reflects fondly on that time.

“We were thicker than family, and I’m proud of the Viewridge community (that helped raise each other’s kids and always had each other’s backs).” One of his favorite memories is coaching Little League here. He was teary eyed as he told me about the grown man who came back one day to thank him for years of mentorship, calling Bill his second father. Bill is exceptionally proud of the impact he had on the kids who grew up alongside his own brood.

“I love our community, and I love this country!” he tells me.

Tom Brokaw coined the term, “the greatest generation” about the men and women who bravely entered the war effort. They sacrificed much and then built the world we have today. I asked Bill if he missed his time on the Sailfish.

He replied, “one of the best things I ever did in my life was join the submarine service.” As this issue goes to print, Bill has five weeks until his birthday; if you see him around town, please wish him a happy one, and salute him for his hard work and devotion and a life that continues to be well lived.