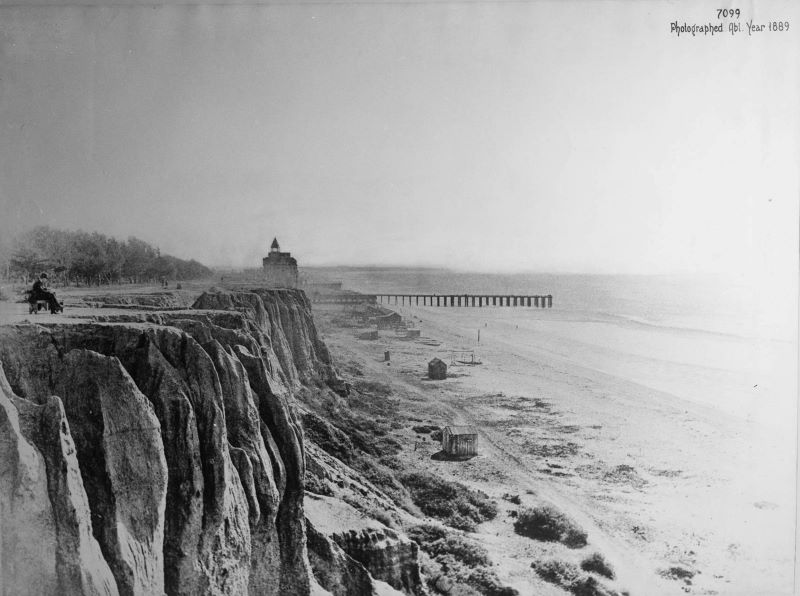

It loomed above the beach like Count Dracula’s beach residence: stark, turreted, treeless, and not exactly inviting, but Dracula wasn’t written yet when the imposing Hotel Arcadia opened its doors in Santa Monica on January 24, 1887. Celebrated for its size and luxury even in the Gilded Era, the Arcadia became the second largest hotel in Southern California—only the Raymond in Pasadena was bigger. It cost an impressive $65,000 to build, boasted a beach-side ballroom that could accommodate 200 couples, 126 rooms and suites, a bowling alley, observation decks protected by walls of glass, and its own private railroad, sometimes described as a rollercoaster.

The Arcadia was only there for a generation. By the time the twentieth century rolled in, Hotel Arcadia’s glory days were behind her. By 1910, this grand dame was history. Today, no trace remains, but the stories still endure.

In the early years, the Arcadia was everything her builder dreamed she would be. That builder was Jesup W. Scott. He was previously the proprietor of the Santa Monica Hotel, on the bluff above Santa Monica Canyon, in partnership with J.H. Hodgeson. The hotel began life as a modest building with just a few rooms and grew to be an impressive structure with four massive chimney stacks and more than twenty rooms before it burned to the ground in 1889. Scott was a canny businessman who saw the tourist potential for the newly founded city of Santa Monica—he even tried to work in an anti-competition tax when the city incorporated in 1886, campaigning for a $1,000 fee for new hotels and bathhouses. It didn’t work, but Scott still came out ahead.

He purchased a swath of land at a bargain price of $3,500 from the Southern Pacific Railroad Company in 1885 on the condition that he build a “fine” hotel. He subdivided the land into 40 lots, sold 30 for $1,200 each, and used the resulting $27,000 to begin work on Arcadia. The railroad’s Pacific Improvement Company also had a stake in the project. It was part of the railroad’s plan to develop destinations for train passengers.

When it opened in 1887, the Hotel Arcadia became Santa Monica’s first luxury hotel. It was designed by architects Solomon Irmscher Haas and William Alciphron Boring (Boring’s Old Plaza Firehouse near Olvera Street remains an LA landmark and cost $65,000—a fabulous sum for the time.)

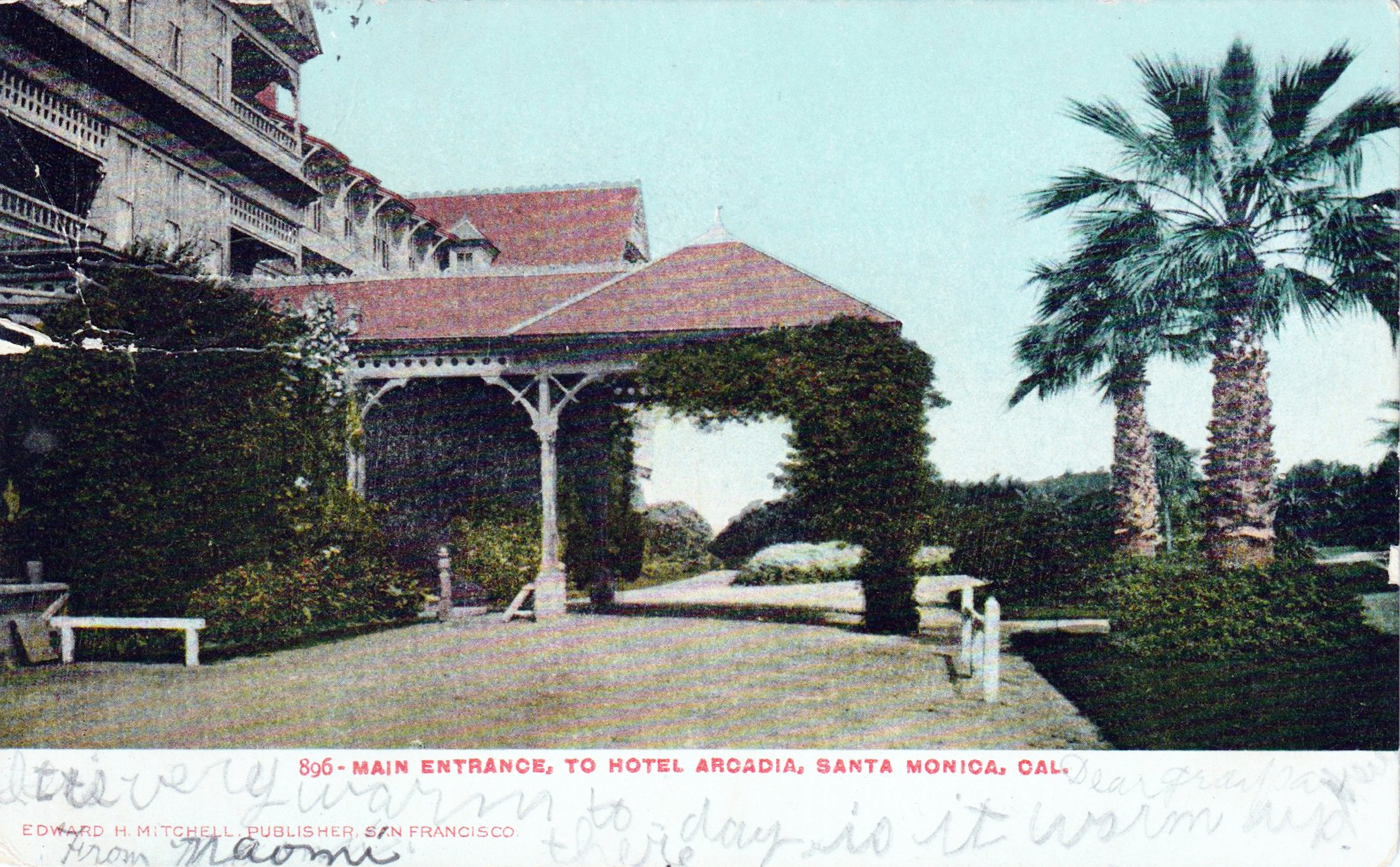

This grand dame of Santa Monica hotels was named for Arcadia Bandini de Stearns Baker, the richest woman in California in her day and one of the founders of Santa Monica. It resembled her, too; large, gracious, and seemingly permanent. The exuberant late Victorian style was modeled, perhaps, on the English beach resorts that would provide such fertile ground for mystery writers a generation later.

The Hotel Arcadia was five stories high and dominated the skyline for miles. The hotel featured every imaginable luxury. The Los Angeles Times enthused that every room had an electric bell, that there was a special billiard room for ladies, and a glassed-in sun parlor where, “invalids can enjoy the solar rays without any wind.” The furnishings and decor were “extremely elegant” and, “1000 yards of carpet were required for the halls alone.”

An 1893 advertisement boasts about the hotel’s sea baths: “physicians recommend them for health and vigor!”

“Hot salt water baths may be enjoyed by those who cannot stand the cold water [in the ocean]…another ad states. “[The Arcadia] stands without a peer for furnishing true, modernized life at the seashore. According to that 1893 description, guests enjoyed “gas and electric light, hot and cold water, bathrooms, and all modern improvements…”

Transcontinental travelers and wealthy Angelenos came here in summer to escape the heat inland. They took the sun in glassed in sun porches, and bathed in tubs that featured heated sea water. They gathered on Sunday evenings for formal balls and danced to music provided by a live orchestra, they listened to lectures on art, and were sometimes swindled by professional hotel sharks. Hardy souls might swim in the ocean or take a day excursion in a stage coach or hay wagon up the coast to exotic locales like Arch Rock, and the mouth of “Topango” Canyon. Or they might explore the little Japanese fishing village beside the Long Wharf, or picnic in Santa Monica Canyon.

For the first few years, new arrivals could take the hotel’s private gravity switchback railroad from the train depot to the hotel. Sometimes described as a rollercoaster, this slow-moving conveyance was designed to cross a steep, 500-foot-wide ravine, using gravity to propel it up the bluff on the other side. When visitors arrived they might rest for a moment in a seat on the 200-plus-foot long porch and gaze with wonder at the Pacific.

The hotel attracted a wealthy clientele that included visitors but also Angelenos who booked rooms or suites for months at a time. Society columns indicate that Frederick Hastings Rindge and his wife May Knight Rindge were visitors in 1891, shortly before the couple purchased the Malibu Rancho.

In 1894, the hotel hosted railroad baron and Southern Pacific president Collis P. Huntington, who arrived in Santa Monica in his private railroad car. Huntington was there to visit the Long Wharf, grandly titled the Port of Los Angeles. This 4,720-foot-long pier was built by Southern Pacific Railroad as part of Huntington’s unsuccessful plan to turn what is now Will Rogers State Beach into the deep-water port for Los Angeles, instead of San Pedro. Huntington wanted a monopoly on the port railway for the rapidly growing city of Los Angeles. Access to the Long Wharf was limited to the coast route, and Huntington owned that right-of-way. The wharf, constructed in an amazingly short period of time, was built on wishful thinking. The open ocean conditions in the north Santa Monica Bay were too rough for a successful port, and that was just one of the reasons San Pedro was favored by other powers.

The Long Wharf dominated the view of the horizon from the Arcadia when Huntington visited—he might have admired it from the windows of the Presidential Suite during his stay—but his plan didn’t work. By the turn of the twentieth century, the era of the railroad was already running out of steam, and so was the Hotel Arcadia.

Historian W.W. Robinson describes the period that produced the Arcadia and the Long Wharf as Santa Monica’s “Great Boom.” Along much of the California coast, that boom was fueled by money from the railroads. Hotels and resorts were developed to drive the need for railroads, but the boom wasn’t sustainable. The hotel and the rapidly growing community of Santa Monica would be hit hard by the Panic of 1893, a nationwide economic depression that lasted until 1897, abruptly chilling the enthusiasm of the Gilded Age, and offering a grim preview of coming attractions in the rapidly approaching twentieth century. The Arcadia never entirely bounced back.

Although the Pacific Improvement Company retained control, the management changed frequently during Hotel Arcadia’s brief existence. The hotel went from dominating North Beach to being eclipsed by the lavish Ocean Park bathhouse, with its Arabian Knights domes, and by new delights like roller coasters and carousels at the Santa Monica and Venice piers. These attractions drew crowds of ordinary people, instead of a select, wealthy clientele.

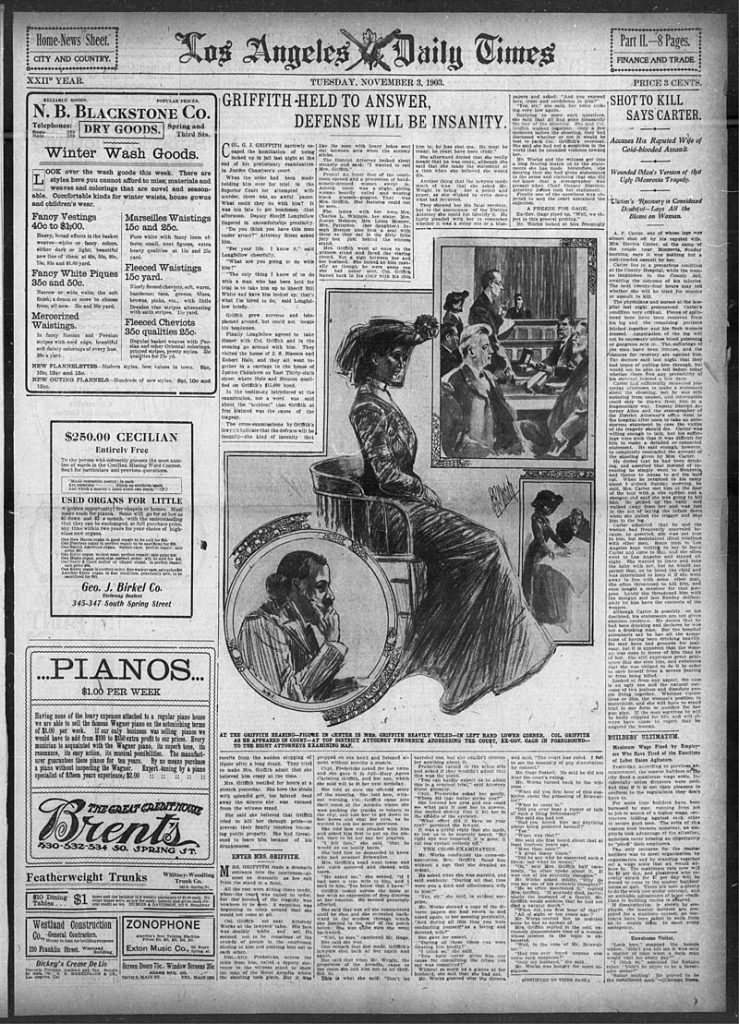

Today, the Arcadia remains most famous—or infamous—as the location where wealthy would-be socialite Griffith J. Griffith attempted to murder his wife, Mary Agnes Christina “Tina” Mesmer Griffith, in 1903.

Tina was a wealthy heiress. Griffith arrived in California a Welsh immigrant with ambition but no money. He began work as a journalist, became a mining correspondent for the Alta Californian San Francisco newspaper, and used the knowledge he gained to become a mining consultant. He made a fortune, but was widely seen as an opportunist. Griffith added the title “Colonel” to his name presumably to give himself gravitas, but he could never shake the reputation for being a grasping and arrogant man.

The couple had completed a summer-long stay at the Arcadia and were headed home to Los Angeles. Tina was busy packing up for her husband and 15 year old son, when Griffith, in an alcohol-fueled paranoid rage, shot her in the face. He did it execution-style, making Tina kneel before him. He accused her of being unfaithful and of trying to poison him before he pulled the trigger. She survived, although the bullet struck her eye almost point blank. She wrestled with Griffith for the gun, then threw herself out of the suite’s window to escape from him. She fell two stories onto a balcony roof and broke her shoulder bone, but was still able to scramble through a window to safety. Tina lost an eye and lived the rest of her life with facial scarring. Griffith spent three years in prison—one in the county jail awaiting trial, before being sentenced to two years at San Quentin. He was fined $5,000, and ordered to seek “medical aid for his condition of alcoholic insanity.”

The incident, the culmination of what must have been years of terror for Tina, enabled her to obtain a divorce—not an easy thing in 1903, even for someone who had just survived an attempt at murder. She also negotiated a settlement that included $62,500 in lieu of alimony—about $2.3 million in 2024. She also won sole custody of their 15-year-old son Vandall, and Griffith agreed to provide a trust fund for him to attend Stanford.

Griffith became an advocate for prison reform after his stint at San Quentin, but his temper and arrogance, and the crime he committed prevented him from ever achieving the social success he craved.

Griffith’s contribution of Griffith Park to the city of Los Angeles, together with the money to build the Griffith Observatory and the Greek Theater, ensured that his name would be remembered for something other than his attempt to kill his wife. Tina moved in with her sister and became a recluse. She appeared at the trial with a veil over her scarred face. Newspaper accounts provided dramatic illustrations and diagrams showing the window she left from and the one she climbed through to safety. The story dominated the headlines for weeks, and attracted sensation seekers, but it did little to draw paying customers to the hotel.

By 1908, the huge building stood empty. One account states that it offered accommodation only to bats. The Hotel Arcadia was demolished in 1909. The Club Casa Del Mar (currently the Casa Del Mar Hotel) and the Edgewater Beach Club (rebuilt in the 1990s and now Shutters on the Beach) were built on the site of the Arcadia in the mid 1920s. They represent different times and different aesthetics, but they still attract visitors for the same reasons they came to the Hotel Arcadia: sun, sand, sea, and an opportunity to enjoy life at the beach.

Suzanne,

Hello!!!, my wonderful writer friend. I always look for your amazing stories, a collection that seems to grow and grow. Your research is stunning, as with this edition.

We have moved into our new house.. But returning to a bit of “normal” eludes us. The house is mostly wonderful, comfortable and captures many qualities of our old residents of over 45 years. But much is still a work-in-progress. And the landscaping, as with many rebuilt houses, ours lacks the warmth and character of ‘old” favorites plants and gardens. Slowly, but it will take decades to have gardens in this yard again. We are not complaining, as we have learned how to be more patient. Today a small long-tailed weasel “popped’ around my front window, in the middle of the day. Oh my goodness…the animals are slowly returning. And I am so happy to have him remind us…this is amazing…living in a house again.

Would love to see you. Warmest thoughts…Dawn