A green tsunami of weeds is rising throughout the Santa Monica Mountains this spring. This living tide of vegetation threatens to drown the native plants, but it’s also fascinating. The individual plant species that comprise the army of invaders are a living record of California’s history of colonialism, homesteading, and urbanization.

Some of the most widespread invasive species were among the first to arrive, brought by the Spanish and Mexican colonists. We know this, because their seeds have been found in 200-year-old adobe bricks. Other weeds are more recent escapees: flowers imported to grown in gardens, or seeds that have hitched a ride with more desirable crops. Weeds are ubiquitous, they grow among the crops in the field, and in our garden, and along the side of the road, they invade our parks and open space, but even the most common weeds are worth a second look.

Many common weeds are edible or medicinal, others are poisonous. Some are invasive, others are benign, all of them are interesting. Finding uses for abundant invasive species instead of foraging for native plants is an ecologically sound approach, but it is critically important to accurately identify potentially edible plants and understand that even the most seemingly innocuous ones can have a dark side.

Like human armies, most successful invasive plant species have an arsenal of weapons that enable them to conquer and colonize, and like humans, some of these are chemical weapons: saponin, oxalic acid, and nitrates that make them undesirable to grazers and browsers. Caustic sap, or irritating spines and thorns are other defenses, so are chemicals that poison the soil and eliminate competitors’ seeds—allopathic chemicals. A few weeds are simply so toxic that nothing eats them and survives. Even the most benign weeds need to be treated with respect. Before attempting to handle or eat anything in the wild make sure you are 100 percent certain you know what it is and that it comes from a clean, safe source.

Weeds are reviled for their role in disturbing and permanently altering native ecology—and it is a major role, one that ecologists, farmers, gardeners, and firefighters grapple with constantly in California, but just like us, these plants have come to this place and become part of it. Even the humblest and most ordinary among them has a name, and a history, and a story, and they live directly alongside us, whether we want them to or not. All of the plants in this feature were found within a few hundred feet of the author’s home.

Meet the Weeds

Mustard

The brassica family includes some of the oldest cultivated crops, plants that have helped humans survive famine and stave off illnesses like scurvy. This family includes turnips and cabbages, but it also includes one of California’s most troublesome family of weeds, the non-native mustards.

The story that black mustard, Brassica nigra, was seeded by the missionaries along the El Camino Real to mark the road between the missions is pure fiction, but there is a mustard seed’s worth of truth in it. Mustard is one of the earliest plants that arrived with the Spanish. It’s native to the Mediterranean climate in Southern Europe, North Africa and the Middle East, where it has served not only as the source of mustard seed for a condiment but as a spring vegetable, and a medicinal plant. It quickly adapted to life in California, spreading rapidly to become the dominant plant in disturbed soil along the coast.

Hirschfeldia incana, hoary mustard, is another pest introduced by the Spanish. It’s shorter than black mustard, its flowers are less golden, and it has grayish, hairy leaves. Like black mustard, hoary mustard is a major problem. Both overwhelm native plants, using their own unique form of chemical warfare to poison the soil, releasing allopathic chemicals that prevent other seeds from germinating.

Mustard plants ward off predators with the toxin iso-thio-cyanate, which makes these plants unpalatable to grazing animals and can cause skin and stomach irritation in human foragers. The young leaves of both types of mustard are edible in moderation, cooked or raw. The flowers are more appetizing, less bitter, and aren’t easily mistaken for anything else—all members of the brassica family have clusters of flowers with four round petals.

Foragers have occasionally mistaken the new leaves of tree tobacco (Nicotiana glauca) for mustard greens, with devastating results. In the early 1970s, a local family foraging for wild greens became ill after eating tobacco. Two of their children almost died.

As beautiful as the flowers of mustard are, this is one family of weeds that deserves no mercy. Uprooting it before it goes to seed is the only way to stem the tide of alien gold that covers our hills in the spring and creates fuel for wildfires in the fall.

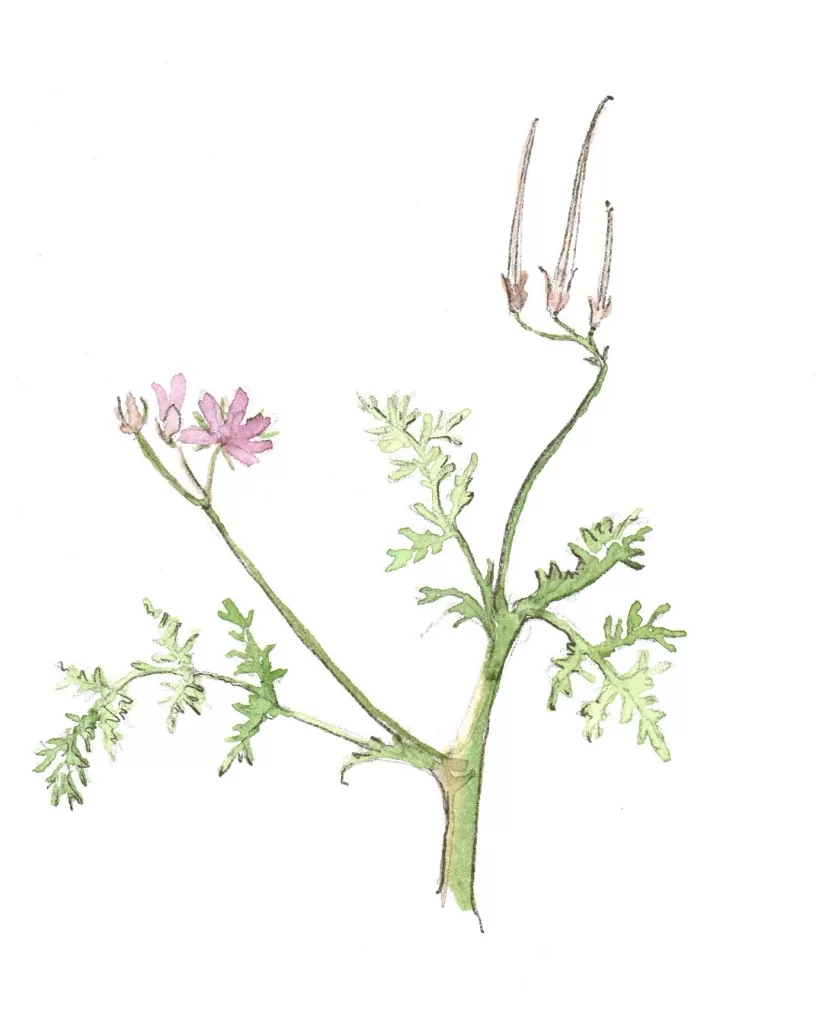

Filaree

There are several plants that go by the name filaree. Like mustard, these members of the geranium family came to California with the Spanish and Mexican colonists, and just like the mustard, they have become a major problem as invasive species.

Redstem filaree, Erodium cicutariium, also known as cranesbill, is the most common in the Santa Monica Mountains. It’s a low-growing winter annual that can linger as a short-lived perennial. The association with birds comes from its beak-shaped seed pods.

Redstem filaree has hairy, finely divided leaves, small purple flowers, and sharply pointed seeds that burst from the pod in a corkscrew shape that can easily work its way into the coats of passing animals. Filaree is said to have arrived in California in sheep’s wool, but it could just as easily have escaped from cultivation. It has a long tradition as a folk medicine for dysentery—a disease that was a potentially fatal health issue for California’s colonists.

Filaree isn’t allopathic or toxic like mustard, but each filaree plant can produce thousands of seeds, enabling this plant to outcompete native species.

Other types of filaree include the aptly named musky storksbill, Erodium moschatum, which has broader leaves, a more pungent scent, and prefers shadier habitat. Like redstem filaree, musky storksbill has small purple flowers and is edible, but it is usually bitter.

Young shoots of filaree can be used as a salad green or cooked vegetable. Redstem filaree could potentially be mistaken for young leaves of deadly hemlock, one of the nastiest non-natives. Hemlock is smooth—never hairy—and looks more like carrot tops. If in doubt, don’t eat it.

Sow Thistle

Sow thistles also staked a claim in the Santa Monica Mountains with the arrival of the first Spanish colonists. Two types of sow thistle are common in the Topanga area. Sonchus oleraceus, the common sow thistle, and Sonchus asper, the prickly sow thistle. Sow thistles crop up everywhere and have mastered the art of survival, growing only big enough to generate a single flower or two during dry years, burgeoning forth into three-foot-high giants with dozens of flowers and thousands of seeds when conditions are right. Both varieties of sow thistle are edible, but just like their relative the dandelion, they can be extremely bitter.

Outdoor survival expert Christopher Nyerges is the author of How to Survive Anywhere, Foraging California, and A Guide to Wild Foods and Useful Plants. Sow thistle is one of Nyerges’ favorite salad greens. He describes it as “the closest thing to lettuce you’re going to find in the wild,” and a rich source of vitamins C and B. Seventeenth century British poet and philosopher John Milton was less sanguine. He uses it as a symbol for something inedible and of no worth: “the asinine feast of sow-thistles and brambles which is commonly set before [youth] as all the food.”

Nettleleaf goosefoot

Like mustard and sow thistle, nettleleaf goosefoot, Chenopodium murale, arrived with the first Spanish colonists. Its seeds, together with black mustard and filaree, have been identified in 200-year-old adobe bricks from Monterey County. Remarkably, the seeds of the goosefoot were still viable—no wonder this plant is so successful.

Goosefoot belongs to the amaranth family, together with spinach and quinoa. The young leaves and stems of goosefoot can be cooked and eaten as a vegetable in moderation—they contain saponin, which can cause digestive problems. The dried seeds are nutritious, but harvesting them is time consuming and they need to be carefully washed to remove the bitter saponins. Young plants of nettleleaf goosefoot really do resemble stinging nettle (which is also edible, but only after cooking removes its sting). Use caution—or even better, gloves—when handling.

Chickweed

Common chickweed, Stellaria media, is native throughout Northern Europe and Asia. It is thought to have traveled here with the Homesteaders in the late nineteenth century—its seeds mixed in with crop seeds. Chickweed has a pleasant, mild, green flavor. It isn’t tough, leathery or bitter, and while it does contain saponins—toxic chemical compounds that the plant uses to repel predators and parasites—one would have to eat a lot of it to have a negative reaction. The leaves and stems make a nice addition to a salad. Chickweed can be cooked as well, but rarely grows in sufficient abundance in this area to serve as a vegetable on its own.

In European folk medicine tradition, chickweed is a “cooling herb,” used to treat aches, pains and inflammation. It is also a good source of vitamin C. Chickweed is one of the seven herbs that are a traditional ingredient in “Nanakusa no sekku,’ a Japanese New Year’s dish made with the earliest spring greens.

Chickweed tends to crop up in urban settings and isn’t a big problem as an invasive. The star-like flowers that give this plant its scientific name—Stellaria—are tiny and rapidly shed their petals.

Curly Dock

Curly or yellow dock, Rumex crispus, has long leaves that begin to curl around the edges as they mature, giving the plant its common name. It grows in wet soil on the edge of ponds or in disturbed soil in the garden—it doesn’t mind clay. Like chickweed, this is a species that is thought to have traveled to California from its native Europe and Asia in crop seeds. It’s a wide-spread weed that grows almost everywhere.

The seeds of this plant are dried and preserved and sold by florists and at craft shops. Young leaves have a sour tang that makes a nice addition to salads, a garnish for soups, or a cooked vegetable, but that tang is created by oxalic acid. Too much dock can cause an upset stomach and has the potential to be life-threatening for livestock. The dried seeds are edible, and can be roasted and ground up—papery outer pod and all—and used in any recipe calling for buckwheat, which is a relative. The seeds can also be used as a coffee substitute, and as a natural dye that produces a pinkish brown pigment.

Little Mallow

Like sow thistle, little mallow, Malva parviflora, takes advantage of whatever resources are available. In a bad year it may only grow to be a few inches tall. In a good year it springs up into a three-foot giant. This is another stow-away that arrived in California with crop seed. The young leaves are edible in moderation, but this is a plant that absorbs and stores nitrates and other chemicals, including pesticides, which can be a problem for anything that eats it in large quantities.

Little mallow gets its other name, “cheeseweed,” from its fruit, which resembles a tiny wheel of cheese. It’s no coincidence that its small purplish flowers resemble hibiscus—mallow is in the same family. The color “mauve” is derived from the Latin word Malva. It was coined by William Henry Perkin, who created the first synthetic dye in 1856, and named it “mauveine,” for the pale purple flower.

Oxalis pes-caprae

All along Topanga Canyon Blvd, and in almost every garden from Malibu to Pacific Palisades, fluorescent yellow oxalis flowers are currently blooming in profusion. This energetic invader, officially named Oxalis pes-caprae—goat-foot oxalis—arrived in the Santa Monica Mountains from its native South Africa in the early 20th century. A 1947 nursery ad in the Malibu Times offers the earliest mention of the plant in the local area. Here’s a quote: “Scratch up whatever soil you find in your garden and push in some oxalis bulbs. They will surprise you!”

Oxalis has thrived, escaping from gardens to grow in abundance on roadsides and in open fields. So far, it hasn’t traveled far from the gardens it has escaped from, but this is a highly successful weed that threatens to become invasive. The shamrock-like green leaves and almost luminous yellow-green flowers are edible, although they should only be eaten in moderation, because the plant contains high levels of oxalic acid. The acid gives the plant its characteristic sour taste and makes it a favorite with children, who like to chew the flower stems, but it can cause stomach upset in high concentrations.

Periwinkle

Periwinkle, Vinca major, is another garden escapee. It entered the lexicon as a color in the early twentieth century, named for this perennial groundcover’s pale purple-blue flowers, but long before that it had an old association with magic. The prefix “peri” is an old word for fairy. “Periwinkle,” or “perivinca” translates as fairy violet, and it’s sometimes called sorcerer’s violet, and fairy’s paintbrush. In Italy, it was also known as “fiore di morte,” because its evergreen vines were used to make wreaths for the dead.

Planted for its ability to grow in the shade and survive drought conditions, periwinkle has escaped from the garden to become a riparian pest, lowering diversity and pushing out native plants. Periwinkle contains alkaloid toxins in its milky sap, but the intensely bitter taste makes it unlikely to tempt anyone to take a second bite. However it should be kept away from pets and small children.

These are just a few of the weeds that have made themselves at home among us. There are many more. Each with a name and a story.

Nasturtium

Nasturtium, Tropaeolum majus, is another relatively recent escapee from the garden. This beautiful plant, with its round leaves and art nouveau festoons of orange and yellow flowers, originates in South America. It thrives in moist soil and shade, and has become a pest in riparian areas along the California coast. So far, nasturtium is mostly restricted to areas where the plants spread directly from gardens into the wild. The flowers, leaves and seed pods are edible and have a peppery flavor that adds zest to salads. That peppery flavor is produced by a chemical similar to the one found in mustard that enables this plant to avoid predation and aids its campaign to muscle out other vegetation.