We have a new neighbor in the Santa Monica Mountains. On April 23, National Park Service biologists captured and radio-collared a 210-pound black bear in the western Santa Monica Mountains, south of the 101 Freeway. The bear, a young male named BB-12, is estimated to be about 3-4 years old. Biologists weighed and measured him, took biological samples, attached an ear tag, and fitted him with a GPS radio-collar.

BB-12 is the first bear in the Santa Monica Monica Mountains to be tagged and added to the NPS wildlife study, but he isn’t the first black bear to successfully make the perilous trip across the 101 freeway from the Simi Hills. There have been occasional sightings of black bears in the local mountains, including remote camera images captured near Malibu Creek State Park in 2016, and remains recovered in 2000 at the site of a landslide, but there is no evidence that any bear of any kind has made its permanent home in the Santa Monica Mountains since the California grizzly bear was hunted to extinction in the late 19th century.

Black bears aren’t native to Southern California—they were imported from the Sierras in 1933 to fill the vacuum left after the eradication of the California grizzly, Ursus arctos californicus, which once thrived throughout the state, including in the Santa Monica Mountains. The California grizzly was a subspecies of brown bear, far bigger than the black bear. Like its close relative the Kodiak grizzly bear, the California grizzly was a giant that could stand more than eight feet tall on its hind legs and could weigh more than 1,200 pounds.

The California grizzly was revered by many Native American Indian cultures. Despite its size, power, and reputation, this bear was a mostly gentle giant, preferring to avoid conflict. That didn’t save the species from being vilified as man-eating monsters by the Spanish, Mexican, and Anglo colonists who arrived in the 18th and 19th centuries. By the beginning of the 20th century, this once widespread and abundant cornerstone species was extinct.

In his 1903 book, Bears I Have Met—and Others, journalist-turned-bear-hunter Allen Kelly described the California grizzly as, “One of the most amiable and well-behaved denizens of the forest…Like most outlawed men, he has been supplied with a reputation much worse than he deserves as an excuse for his persecution and a justification to his murderers…every man’s hand has been against him, but seldom has his paw been raised against man except in self-defense…”

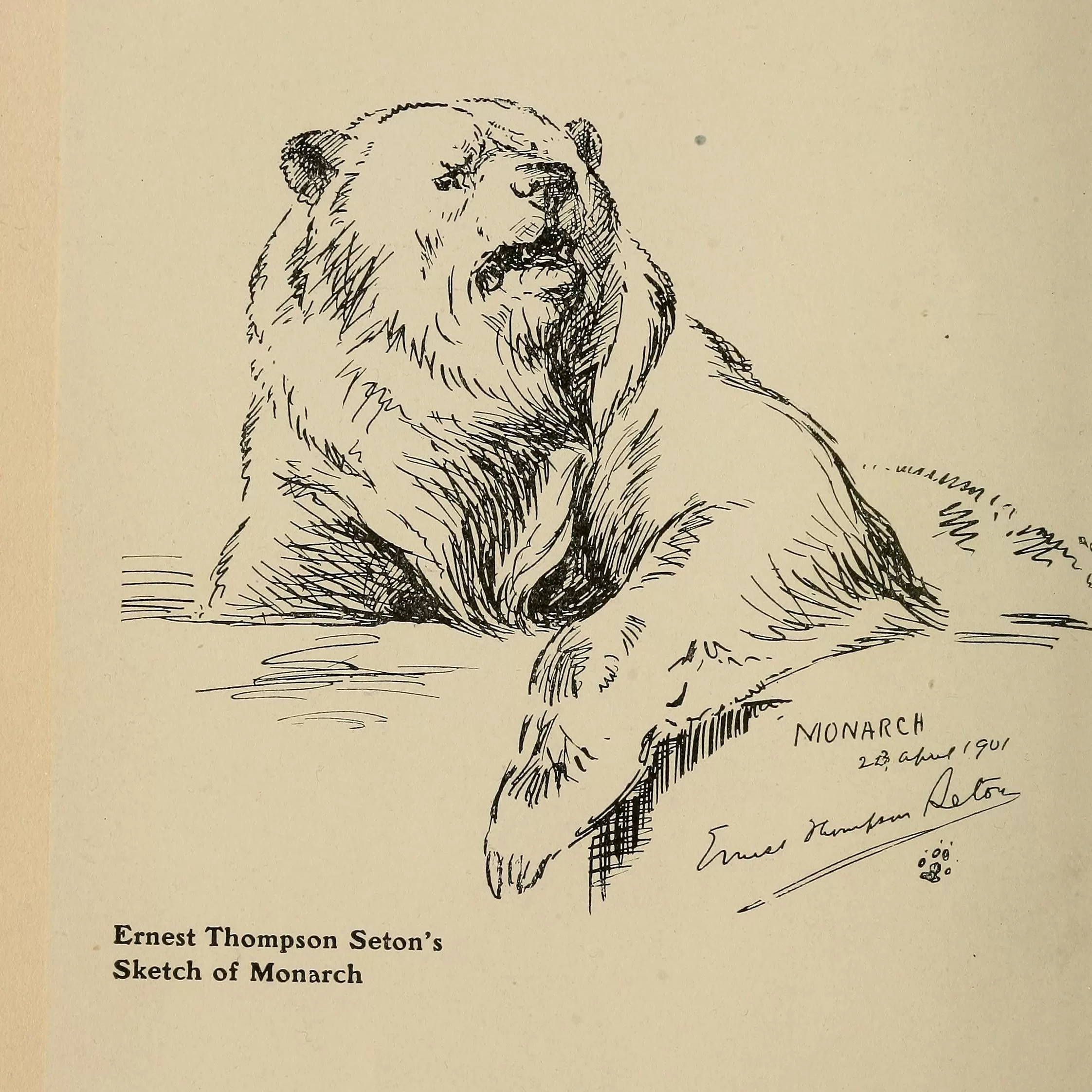

California grizzly bears were already critically endangered when Kelly was hired by newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst in 1889 to capture a live bear for a publicity stunt. He successfully acquired “Monarch” from a team of Mexican trappers in the Ojai Valley of Ventura. The bear was the last—and one of the only— adult wild California grizzlies to have been taken alive and kept in captivity.

The unfortunate Monarch lived in a small cage in Woodward’s Gardens in San Francisco for 22 years. By the time of his death in 1911, California grizzly bears were almost completely extinct. Kelly came to deeply regret his actions. In his book, he recounts how California grizzlies were harried, hunted, tortured, used for blood sports like bull baiting, and killed without mercy.

“I was the only really dangerous and unnecessary animal in the woods, and all the rest were afraid of me,” he wrote.

The last Southern California grizzly is thought to have been one killed on October 26, 1916, by farmer Cornelius Birket Johnson in Big Tujunga Canyon. The bear was killed because it was eating the fruit in the homesteader’s orchard. The last known wild California grizzly was sighted in 1924, near Yosemite.

In 1908, Bertrand Basey, a member of a railroad crew, may have spotted one of the last bears in the western part of the Santa Monica Mountains. He claimed to have seen a “wild man” near Port Hueneme, where the crew was camped. The description he provided to the Los Angeles Times strongly suggests a bear—a shaggy-haired creature that stood up on its hind legs before loping away on four paws, leaving huge footprints on the sand that were, ”not unlike those of a human being, but with the addition of sharp claws.” If it was a grizzly bear, it would have been one of the last not just in the local mountains but in the entire state.

The most famous—or infamous—local grizzly is one reportedly killed by Andrew Sublett in 1854, in the vicinity of Malibu Canyon. There are multiple versions of this story. Adventurer Major Horace Bell gave a melodramatic account in his 1881 book Reminiscences of a Ranger: Early Times in Southern California. Bell arrived in California for the 1849 gold rush and moved south to Los Angeles in 1853. He describes how the bear mortally injured Sublett, and how Sublett died of his wounds with his faithful dog by his side, and how the dog pined away on his grave and is buried at his feet.

Frederick Hastings Rindge, who acquired the entire 14,000-acre Topanga, Malibu, Sequit Rancho in 1892, recorded a less dramatic version of the story. In his 1898 book Happy Days in Southern California, Rindge recounts a conversation with an old homesteader who recalled that the grizzly only broke Sublett’s arm.

If there were still bears in the area when Rindge owned the Malibu Rancho he never mentioned them in his writings, but Malibu grizzly bears did make headline news in March of 1916, when they featured in court testimony given during the fight between the Rindge family and the state over the coast highway right-of-way. A man named Juan R. Ramirez testified that he traveled the coast route in the 1850s, and that it was a well trodden road used by human travelers but not by cattle. The reason? Cattle were not allowed to roam the range because of the abundant bears.

“The cattle had to be kept in corrals because otherwise they would be eaten,” he explained. The privately owned Malibu Rancho provided a refuge for mountain lions, bobcats and badgers throughout the 19th century, but were there also bears? If the story was true, the grizzlies disappeared within a few decades. Hunting reports were a regular newspaper feature in the early years of the 20th century. A July 1906 Los Angeles Times report claimed that bears were abundant in Pasadena and that they “abounded” in Tehachapi, but only deer—not bears—were reported in Malibu.

In 1914, when the directors of the LA Zoo wanted a grizzly to put on display, they had to apply to the Department of the Interior to capture one in Yellowstone, according to a Los Angeles Times article from December of that year—there weren’t enough left in California to make it worth their while to attempt the capture of a local animal.

At the time of the California Gold Rush in 1849, it was estimated that there may have been as many as 10,000 California grizzlies distributed throughout the state. Today, there are just 2,000 grizzlies in the entire lower 48 states, and the animals’ range, which once extended throughout the Western United States, is limited to Wyoming, Montana and a small section of Idaho.

The extinction of the California grizzly bear remains a dark chapter in California’s history. It is grimly ironic that this bear remains the symbol of the state. The grizzly on the state flag is a legacy from the short-lived and unsuccessful attempt made by U.S settlers in 1846 to break away from Mexico. The rebels named their never-achieved utopia the Bear Flag Republic. The bear on the original flag—hand drawn with homemade ink—looked more like a pig than a bear, but his presence has remained even after his species was hunted to extinction. The California grizzly became part of the State Seal in 1849. The bear flag was officially adopted by the California Legislature in 1911. The current version was designed in 1953, the same year the California grizzly was designated the official state animal—three decades after the species was declared extinct.

In 1933, two influential members of the California State Fish and Game Commission who missed the thrill of having bears in the mountains, imported 28 black bears from Yosemite. According to the NPS, “one bear died en route, but eleven were released near Crystal Lake in the Angeles National Forest and the rest in the Santa Ana Mountains and the San Bernardino Mountains near Big Bear Lake.”

Without competition from the larger, stronger grizzlies, black bears rapidly adapted to life at lower elevations and prospered. A small number of black bears make their home in the Simi Hills and Santa Susana Mountains.

BB-12 is thought to have crossed over the 101 into the Santa Monica Mountains near Newbury Park, in the Ventura County section of the range. NPS researchers believe this is the same bear that was spotted walking along Reino Road south of the 101 in 2021. He has since been seen on wildlife trail cameras foraging in the backcountry, from Point Mugu to Malibu Creek State Park.

“He appears to be the only bear here in the Santa Monica Mountains, and he’s likely been here for almost two years based on our remote camera data,” said Jeff Sikich, the lead field biologist of the park’s two-decade mountain lion study. “This seems to be our first resident bear in the 20 years we have conducted mountain lion research in the area.”

So far, BB-12 has stuck to the western and central spine of the Santa Monica Mountains, keeping to the wilder and more remote parts of the range, and has not traveled as far east as Topanga. Black bears are usually peaceful. Attacks on people are uncommon. The NPS offers the following advice:

“If you encounter a bear while hiking, keep a safe distance and slowly back away. Let the bear know you are there. Make yourself look bigger by lifting and waving your arms and making noise by yelling, clapping your hands, using noisemakers, or whistling. Do not run and do not make eye contact. Let the bear leave the area on its own. If a bear makes contact, fight back.”

Hikers who are concerned that they may encounter our new neighbor should consider carrying a whistle or an air horn.

It remains to be seen if BB-12 becomes a permanent resident of the Santa Monica Mountains, or attempts to cross back into the Santa Susana Mountains in search of a mate. Bears are long lived. There could be a future where BB-12 is joined by others of his kind, perhaps establishing a resident black bear population for the first time, more than a hundred years after the last native grizzly bears of the Santa Monica Mountains were killed—a future where bears are a valued part of the ecosystem, not monsters to be feared and destroyed.

Learn more about BB-12 at nps.gov/samo