Books were a very important part of my childhood. TV had not been invented so we learned from books and listening to the radio. And from our elders. The first book that really made an impression was The Story of Dr. Dolittle by Hugh Lofting.

—Jane Goodall, Jane Goodall’s All Good News: Stories of Hope

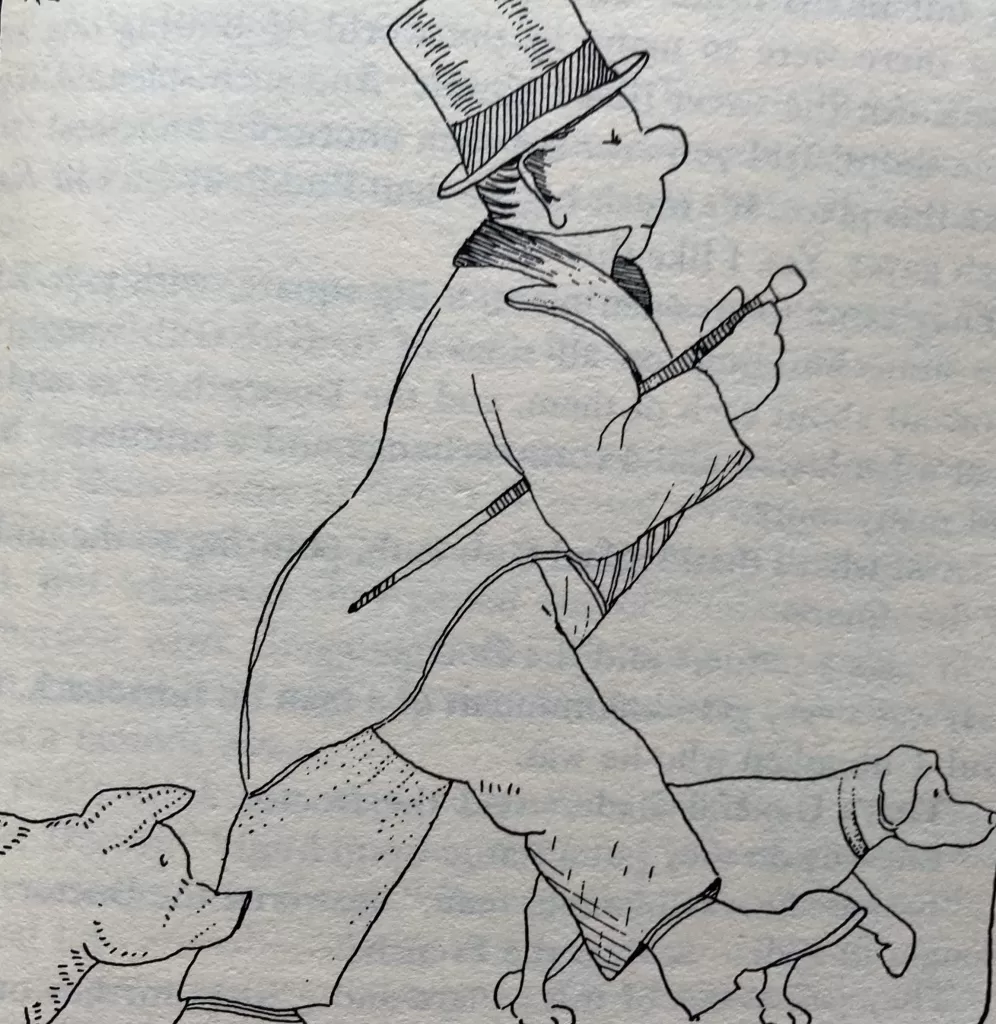

They were gentle, humorous stories about an English country doctor in Victorian times who learned to talk to animals and had extraordinary adventures. I loved them as a child. The Voyages of Doctor Dolittle by Hugh Lofting was the first chapter book I ever read on my own. It introduced me for the first time to the idea of being a naturalist, and planted the seeds of the idea that someday, I, too, could learn enough about the natural world to earn that title. If I thought of the author at all over the years, I envisioned him living in a picturesque English village like his fictional Puddleby-on-the-Marsh and drawing inspiration for his books from the English countryside, like Beatrix Potter, another childhood favorite.

Instead, the kind and gentle Doctor Dolittle, a naturalist who “liked animals better than even the best people” and learned to talk with them in their own languages, was inspired by the horrors and inhumanity the author experienced in World War I, particularly the brutal death of horses and mules that also served at the front line and were killed in huge numbers, without anyone to speak for them.

And while the good Doctor is quintessentially English, the entire series of books were written after Lofting emigrated to America. The author had an early life at least as adventurous as his creation’s, but he spent most of his life in the United States, including several years right here in Topanga.

Hugh John Lofting was born in Maidenhead, Berkshire, England, on January 14, 1886. He was one of six children. Lofting’s mother was tolerant and supportive of her young son’s love of animals, but drew the line at pet mice in the linen cabinet—an incident that made it into the first Dr. Dolittle book. Lofting’s father was an architectural engineer who nurtured his son’s love of drawing, but also encouraged him to pursue a career in engineering.

Lofting came to the United States in 1905 to study engineering at MIT. In the years before WWI, he traveled the world, working as a surveyor in Canada, and then as a civil engineer on railways in West Africa and Cuba. In 1912 he settled in New York. He began his career as a writer with short pieces written for magazines and newspapers. He met and married Flora Small, and the couple had two children, Elizabeth and Collin.

Lofting was still a British citizen at the start of WWI. Initially, he worked for the British Ministry of Information while still living in New York, but as the losses mounted and the war dragged on, he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Irish Guards, and sent to the front in Flanders and France.

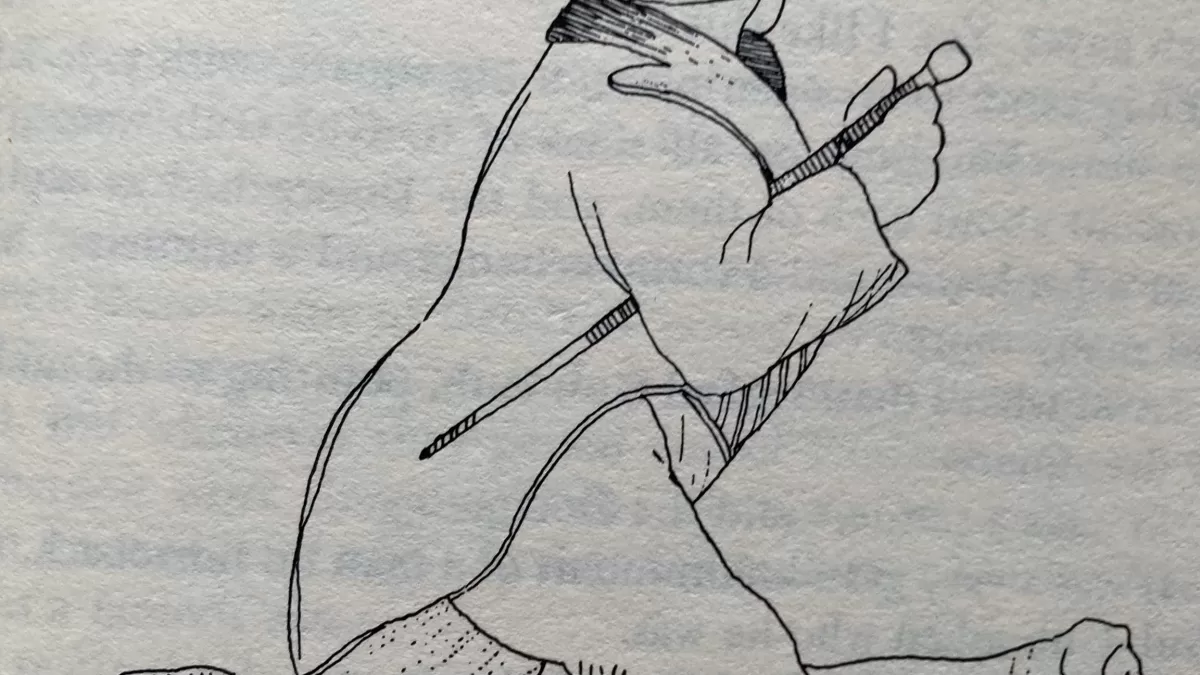

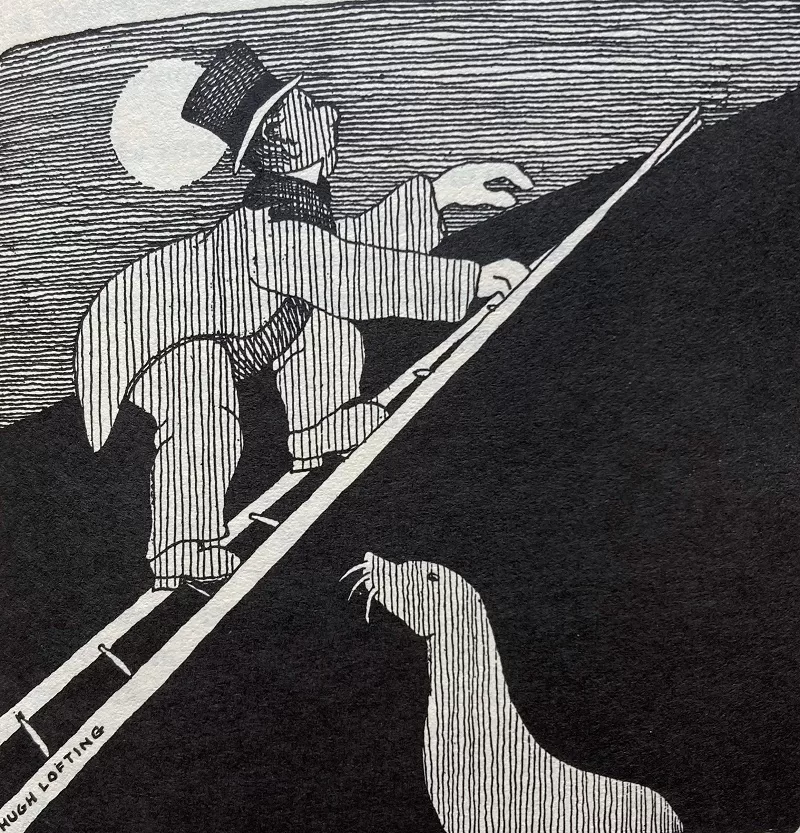

Kindly, gentle Dr. Dolittle, who could talk to the animals, and devoted his life to helping them was born from the death and brutality Lofting witnessed at the front. He couldn’t share the horrors he experienced in the war with his children, so he wrote letters to them about the good doctor, illustrating his adventures with sketches.

Lofting was severely injured by shrapnel from a hand grenade in 1917. Newspaper reports reveal that he was allowed to return to New York to convalesce, and that when he was back on his feet, he worked on the war effort through the YMCA and the Red Cross, giving talks up and down the East Coast to help raise funds and support for the soldiers still in the field. His experiences in the war made him a life-long pacifist. One of his only published works for an adult audience was a long-form poem about the futility of war called Victory for the Slain. It was published in Britain in 1942, on the eve of the US entry into WWII.

The letters from France were carefully saved by Flora, and became the first Doctor Dolittle book in 1920, but it was a difficult journey from the front line of the war back to his life as husband and father, and the dream of becoming a writer.

In a 1967 interview with film critic Roger Ebert, Lofting’s youngest son, Christopher, said his father’s original Dolittle letters from the front lines were a protest of sorts against the war.

“He was appalled by the suffering of animals in wartime,” Christopher said. “There were thousands of cavalry horses in the war, and also farm animals and pets who got caught in the crossfire. My father invented Dolittle, the man who could speak with animals and cure them, as a superhero who could do things he couldn’t do.”

In one of the last Doctor Dolittle books, the author describes war as, “A messy, stupid business…two sides wave flags and beat drums and shoot one another dead. It always begins this way, making speeches, talking about rights, and all that sort of thing.’

‘But what is it for? What do they get out of it?’

‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘To tell you the truth, I don’t think they know themselves.’”

The Story of Doctor Dolittle: Being the History of His Peculiar Life at Home and Astonishing Adventures in Foreign Parts Never Before Printed debuted in 1920 to near universal acclaim. British novelist Hugh Wapole described it as “the first real children’s classic since Alice… In fact this book is a work of genius.”

Lofting envisioned himself writing feature stories and novels for adults. Instead, he devoted the next decade of his life to chronicling the adventures of Doctor Dolittle. Nine volumes were published in his lifetime; two were completed posthumously. Lofting also wrote two picture books for younger readers, a fairytale called Twilight of Magic, and a collection of poems for children, Porridge Poetry.

Lofting’s private life was marred by tragedy. Flora died in 1927. Her passing marked the end of his most productive period as a writer. His second wife became ill and died less than a year after their marriage. In 1935, Lofting married Josephine Fricker. For a time, things were better. The couple moved to California, where their son Christopher was born in 1936. Christopher, who died in 2021, grew up to be a celebrated journalist and a travel writer for Life Magazine. He remembered his father taking him for nature walks and sharing with him his love of the natural world, but Lofting’s health was poor during the last years of his life and his days of travel and writing were over.

Josephine’s sister, Olga Marguerite Fricker, a respected ballet dancer, lived in Topanga in the 1940s. The Loftings were regular visitors. The Lofting family rented a house near hers in 1945, and bought a home of their own on seven acres in the Post Office Tract in 1946, where the author spent the final year of his life. He died in 1947. He was only 61.

Olga was instrumental in preparing Lofting’s last two books for publication. She also wrote a play based on Doctor Dolittle that is still performed.

The Story of Doctor Dolittle celebrated its centennial in 2020 with little fanfare. In recent decades controversy has grown up around the first book. A modernized version was released in 1988 after a decade out of print. The editors addressed controversy over racially insensitive elements of the book involving adventures in Africa by simply removing everything that could potentially cause offense—including an entire chapter, and two pages of the author’s illustrations. Children’s literary critic Selma Lanes, writing for the New York Times Review of Books, quipped that “Doctor Dolittle was innocent again,” while reminding the reader that Lofting himself was aware of the way trends in writing shift over time.

Lanes wrote: “Writing with uncanny prescience in 1930 about a now forgotten book of his called ”The Twilight of Magic,” [Lofting] said: ‘Perhaps we do not realize that fiction reading for children is not the same in our children’s generation as it was in our own…Life cannot stand still…’”

“Happily, none of this well-intended editorial tinkering has had the slightest effect on the tales’ enduring charms,” Lanes concluded. “They still exude the same cheerful optimism about life’s possibilities and the world’s wonders awaiting the reader’s discovery. Perhaps most important, the Dolittle books are enthusiastic about the joy of using one’s mind. What more can we ask of children’s books?”

None of the numerous film and television adaptations have fully captured the charm of the books—or the spirit of the author—but Doctor Dolittle has become part of the pantheon of immortal children’s book characters that continue to live in imagination.

“There is poetry here and fantasy and humor, a little pathos but, above all, a number of creations in whose existence everybody must believe whether they be children of four or old men of ninety or prosperous bankers of forty-five,” Hugh Walpole wrote. “I don’t know how Mr. Lofting has done it. ”Doctor Dolittle, the Complete Collection in Four Volumes, published in 2019, is available from Simon and Schuster. This version has unappealing new cover art in place of the originals, but is sensibly and gently updated and retains author Hugh Lofting’s illustrations in the text and all of the stories’ charm.