“We can’t hope to win the Cold War unless we remember what we [the United States] are for as well as what we are against… I’ve learned that the only time we’re hated is when we stop trying to be what we started to be 200 years ago. Now I’m not blaming my country. I’m blaming the indifference that some of us show toward its promise.”

—The Ugly American, a 1963 film set in a fictionalized “Vietnam,” written by Stewart Stern and based on the 1958 novel of the same name by Eugene Burdick and William Lederer.

Could the Vietnam War have been avoided? For nearly half a century now, discussions of American military interventions—or prospective interventions—have been measured against America’s catastrophic military and political failure in Vietnam.

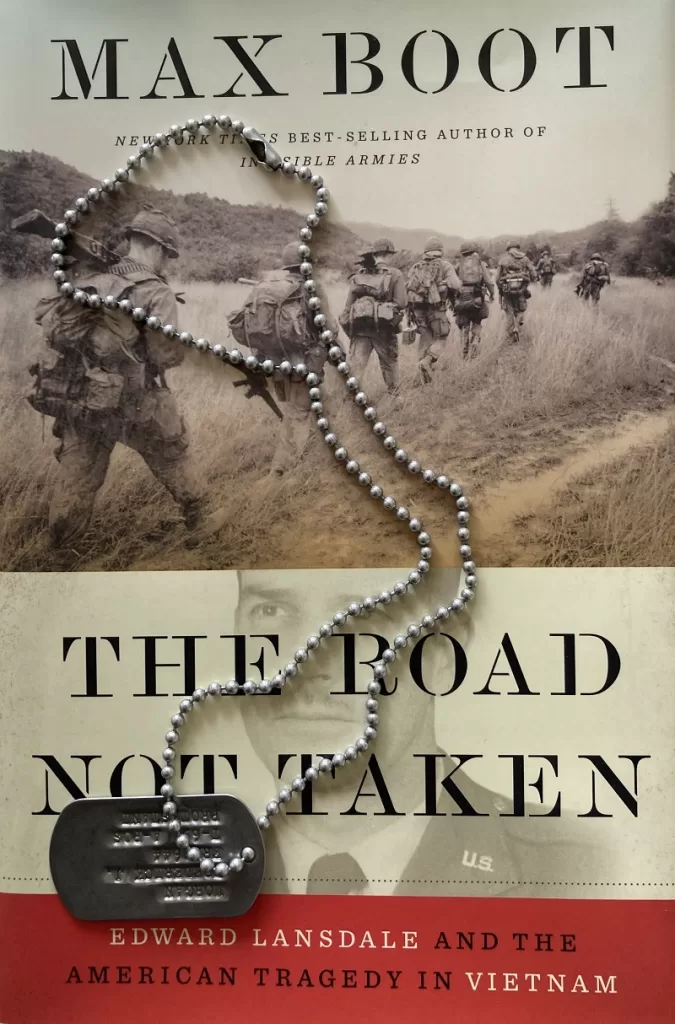

In The Road Not Taken: Edward Lansdale and the American Tragedy in Vietnam (2018), military historian Max Boot strongly suggests that the course of that war could have followed an entirely different path; if only the observations and recommendations of a bureaucratically marginalized dissenter had been heeded. Major General Edward G. Lansdale retired from the United States Air Force in 1963, just as the US was about to ship hundreds of thousands of American troops to a little known country on the other side of the world. More than 50,000 of them would return home in body bags while the number of Vietnamese deaths is estimated at around 1 million, with civilians making up about a third of that total.

This tragedy, Boot writes, “might conceivably have been avoided if only Washington policymakers had listened to the advice of a renowned counterinsurgency strategist who had been present at the creation of the state of South Vietnam.”

Before being assigned to Vietnam, Ed Lansdale developed his skills while serving in the Philippines. In both countries, insurgent groups had organized to resist Imperial Japanese occupation in the early 1940s; the Huks in the Philippines and the Viet Minh in Vietnam. After the Japanese surrendered in 1945, both insurgent groups remained active against oppressive post-war governments in their respective countries. As we’ll see, both the Philippines and Vietnam depended upon the United States for support during the early years of the Cold War.

Lansdale served in the Philippines during World War II and remained there before being transferred back home in 1948. In that time, he developed personal relationships with Filipino civilians and government officials; which is why, in 1950, the president of the archipelago nation personally requested that Lansdale return to assist in developing their intelligence services.

Working as an intelligence officer within what would eventually become the Central Intelligence Agency, Lansdale encouraged the Philippine government to consider that the best way to deal with the Huks was to fight them when necessary while avoiding civilian casualties and, most importantly, consider what social, political, and economic needs they had. Lansdale would spend the rest of his career arguing that understanding the people heavily involved in a conflict, combatants and civilians alike, was critical to any hope of enduring success. The failure to win the hearts and minds of the people has repeatedly diminished the significance of otherwise successful military conquests.

For example, in the Philippines of the 1950s, one of the insurgent Huks’ rallying cries was “Land for the Landless.” Lansdale worked closely with Ramon Magsaysay, who eventually became the Philippine president. Together they developed a resettlement plan that “offered fifteen to twenty acres of free farmland” on a distant island for Huk insurgents willing to surrender.

“Soon,” Boot writes, “Huks were appearing in army camps asking to surrender and demanding to know how soon they could get a farm.” While the actual number of Huks resettled was very low, the “psychological impact was much greater.” The non-threatening message to an aggrieved people was that the Philippine government had the capacity to listen.

In the process, Lansdale and Magsaysay also developed a personal friendship which was key to this evolving “Lansdalian” counterinsurgency strategy: soldiers must be trained as diplomats and practice “civic action.” While in the field, they were to treat the civilian population with respect. Instead of threatening civilians who may have knowledge of insurgents, soldiers were encouraged to carry more food than they needed to share with impoverished villagers, and to carry along chewing gum for the kids.

While American bombers would later wreak havoc across the Vietnamese countryside, Lansdale’s Filipino campaign discouraged aerial and artillery assaults because they inevitably killed more civilians than insurgents.

One program illustrates the broad effort Lansdale made to gain favor with the civilian population. “Magsaysay, with Lansdale’s American intelligence purse strings, imported cheap box cameras from Japan and handed them out to the troops” who were then “ordered to photograph any enemy casualties.”

As Lansdale commented later, the cheap cameras distributed to soldiers in the Philippines “kept the casualty figures down to a point of reality that became remarkably accurate” and “it taught the troops not to go out and shoot women and children and then claim them as casualties.” While women and children were sometimes used as insurgent assets, it is clear that later, in Vietnam, hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians were killed.

American officials would become fanatically obsessed with “body counts” in Vietnam; and this vicious metric became the absurd yardstick of “success” as soldiers in the field were required to report how many of the “enemy” they had killed.

By 1954, the Huk rebellion ended. It was a process that included the implementation of reforms that addressed the concerns of those who had been defeated. Max Boot argues well that the military victory was aided in no small part to the “civic action” and other counterinsurgency efforts of Edward Lansdale working closely with his friend Ramon Magsaysay.

Lansdale’s success in the Philippines led to his deployment to Vietnam to deal with a similar insurgency there. Unfortunately, efforts to duplicate his Filipino success in Vietnam would be undermined by bombastic bureaucrats and politicians; as well as Lansdale’s own stubbornness and impatience in dealing with those in power who he began to despise.

Lansdale’s struggles in Vietnam resonate with modern conflicts and reflecting upon them may yet help to guide American foreign policy in a more humane and thus successful direction. He believed that if one is to understand the people in faraway lands and meet them as human beings, it is necessary to understand their situation, and their grievances, in the context of their history.

While Americans see this episode in our own history as the Vietnam War, the reality is that, for the Vietnamese people, American involvement in their country was only one chapter, albeit an extremely violent one, in a brutal series of foreign abuses.

For centuries, the Vietnamese resisted the imposition of Chinese influence and control, but Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam came under French occupation in the late 1800s and this colonial experience carried with it all the hallmarks of white supremacy: “civilizing” what the French viewed as a backward and inferior people.

The people were subjected to the whims of their French overseers, forced to work in the dirtiest and most difficult jobs, and regarded as unworthy of the most basic human rights. And, most significant for the current review, any resistance to these oppressions was met with violence and brutality. In at least one instance, French officials and their Vietnamese collaborators publicly displayed and photographed the severed heads of insurgents in order to terrorize the population.

During World War II, Imperial Japan occupied French Indochina from 1940-1945 while maintaining an uneasy alliance with the French Vichy government—which had made an uneasy alliance of its own with Nazi Germany. The Vietnamese, organized by Ho Chi Minh, resisted both the Japanese and the Vichy French. These insurgents—the Viet Minh—fought successfully using guerilla-style tactics against a vastly superior military force.

At the end of the war, the Allies reinstated the Free French government in Indochina, which quickly tried to reassert its pre-war colonial dominance. Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh had hoped that their efforts would lead to independence but this would not be the case.

By 1949, following Mao Zedong’s communist victory in China’s Civil War, Vietnam became a Cold War battlefield with Chinese-supported Viet Minh clashing with American-backed French forces.

In 1954, the French military was humiliated at Dien Bien Phu and the prospects for Vietnamese independence were bright. The agreement accompanying French withdrawal—the Geneva Accords—divided the country, with Ho’s Viet Minh controlling the north and an American-backed, yet largely unstable government in the south. Elections to reunify the country were scheduled for 1956.

When Edward Lansdale arrived in Saigon, South Vietnam’s capital in 1954, he worked closely with Ngo Dinh Diem—who became president in 1955—to prevent communist North Vietnam from uniting the country under communist rule. Hypocritically, yet in the dark spirit of America’s many Cold War engagements, the United States blocked the promised national elections of the Geneva Accords because Ngo Dinh Diem and his American counterpart, President Dwight Eisenhower, as Boot writes, did not have “any interest in holding a vote that they were sure would be won by Ho Chi Minh…”

As would occur time and again, America’s fear of communist expansion in the chilliest days of the Cold War trumped the more noble mission of spreading democracy, despite all the rhetoric to the contrary; and it seems as if one of the only ones willing to speak up to this glaring hypocrisy was Edward Lansdale.

Jimmy, Next hill from Topanga, Bernard Brodie, Rand Corp, wrote piercingly and well about horrible US approavh to SEAsia. My Alaska US Senator was nationsal annti-colonial restorations after WWII: ‘VietNam Folly’ . A Brodie book is ‘War and Politics’ , chapters 4 and 5 about Viet Nam. Published in 1971 when he was internationally known is military strategist and peace advocate, “Viet Nam , a story of unmitigated disasters that we have inflicted on ourselves…” Home in Pacific Palisades, he, and his wife Fawn, herself an eminent biographer (Joseph Smith, Thomas Jefferson, c.) lived on the verge of Topanga State Park. Most recent biography of Bernard Brodie ranks him with Clausewitz and Tsun Tsu. Brodie was great mind in formulating strategy to avoid nuclear war. And–the Brodies picnicked on Topanga Creek. Thanks Jimmy, you do write well! Larry Smith, Homer, Alaska