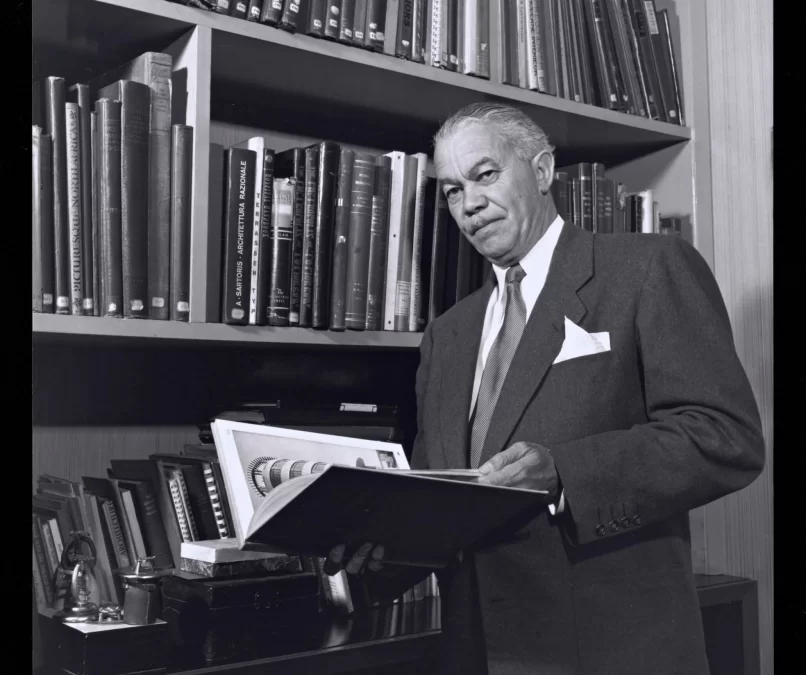

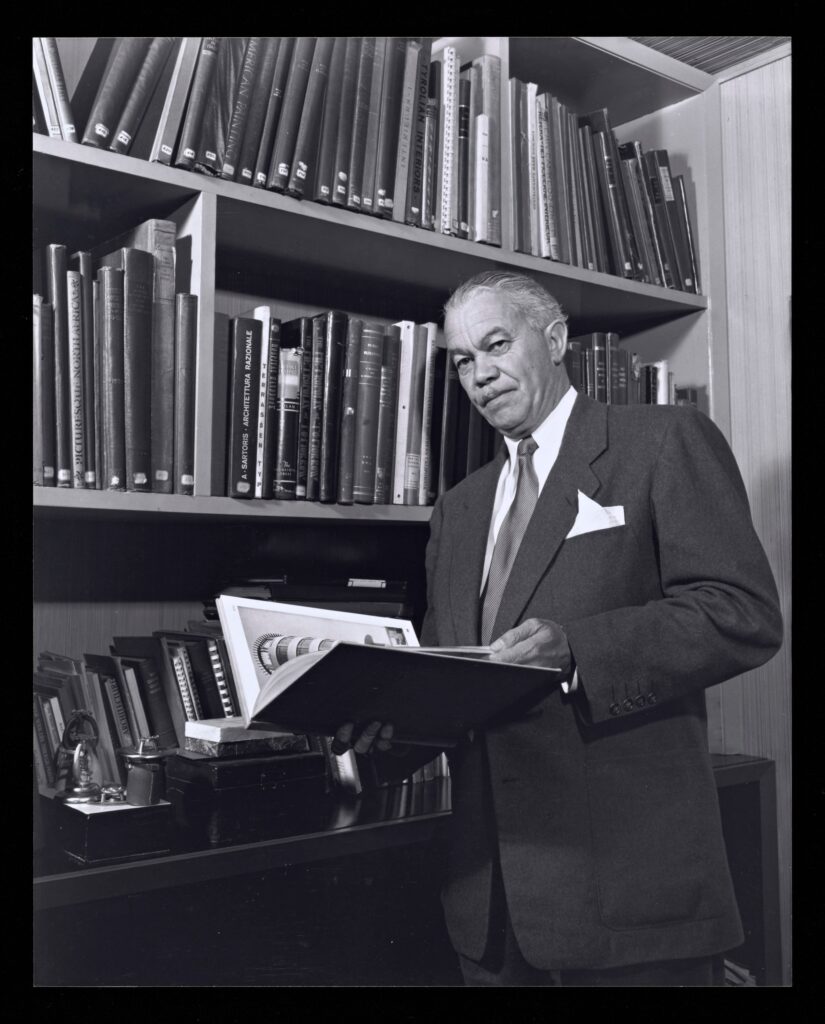

Paul Revere Williams (1894–1980) is considered the most significant African American architect of the 20th century. Williams’ distinctive designs helped shape the glamorous Hollywood aesthetic of the 1930s and Southern California’s iconic mid-century modern character a generation later.

Although many of Williams’ buildings have been lost, his extensive archive has remained intact, thanks to the architect’s granddaughter, Karen Elyse Hudson, who has been the curator of her grandfather’s papers and has published extensively on his work.

That collection contains more than 35,000 plans, 10,000 original drawings, blueprints, and project diazotypes, hand-colored renderings, vintage photographs, correspondence, and other materials relating to both built and unbuilt work. The entire archive was recently acquired jointly by the University of Southern California School of Architecture and Getty Research Institute, ensuring that Williams’ work will continue to be preserved, studied and shared.

Orphaned at the age of four and separated from his brother, Williams spent time in several orphanages before ending up in a foster home where his talents for drawing and design were appreciated.

Williams’ foster mother encouraged him to pursue his growing interest in architecture. When a guidance councilor at his high school told him “who ever heard of a Negro architect?” Williams reportedly replied, “I’m going to prove I can [be one].”

Williams attended art school at night, working his way through the Los Angeles Beaux Arts School. He won a contest to design a civic center in Pasadena, and went on to study architecture at USC from 1916-1919, becoming the first certified African American architect in the Western U.S.

Williams designed hundreds of civic and community buildings—the stately Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company Building in L.A., and the flat-roofed Mid-Century classic Palm Springs Tennis Club, the Los Angeles Founder’s Church of Religious Science with its round design that suggests a mid-century version of a Byzantine church; the elegant Saks 5th Avenue and towering five-story W.J. Sloane department stores on Wilshire in Beverly Hills; the 1940s redesign of the Beverly Hotel with its famous Polo Lounge.

His residential designs embodied the quintessential California indoor-outdoor lifestyle, built around patios with sliding glass doors, and showcased in magazines like Sunset and Architectural Digest. They earned him the title “architect to the stars.”

For Frank Sinatra he built a modernist home around the singer’s state-of-the-art sound system, with speakers in the ceiling and specially designed acoustic walls; for actor Lon Chaney he designed an Italianate mansion in Beverly Hills and a rustic stone chalet in the Sierras; for Lucile Ball and Desi Arnez, the ideal modernist desert retreat in Palm Springs.

Williams designed several buildings in the Santa Monica Mountains, including the Colony Coffee Shop in Malibu. This round building was designed with the kitchen in the middle and booths along the curving walls. It became a local landmark, but was demolished in 1988 despite a campaign to save it.

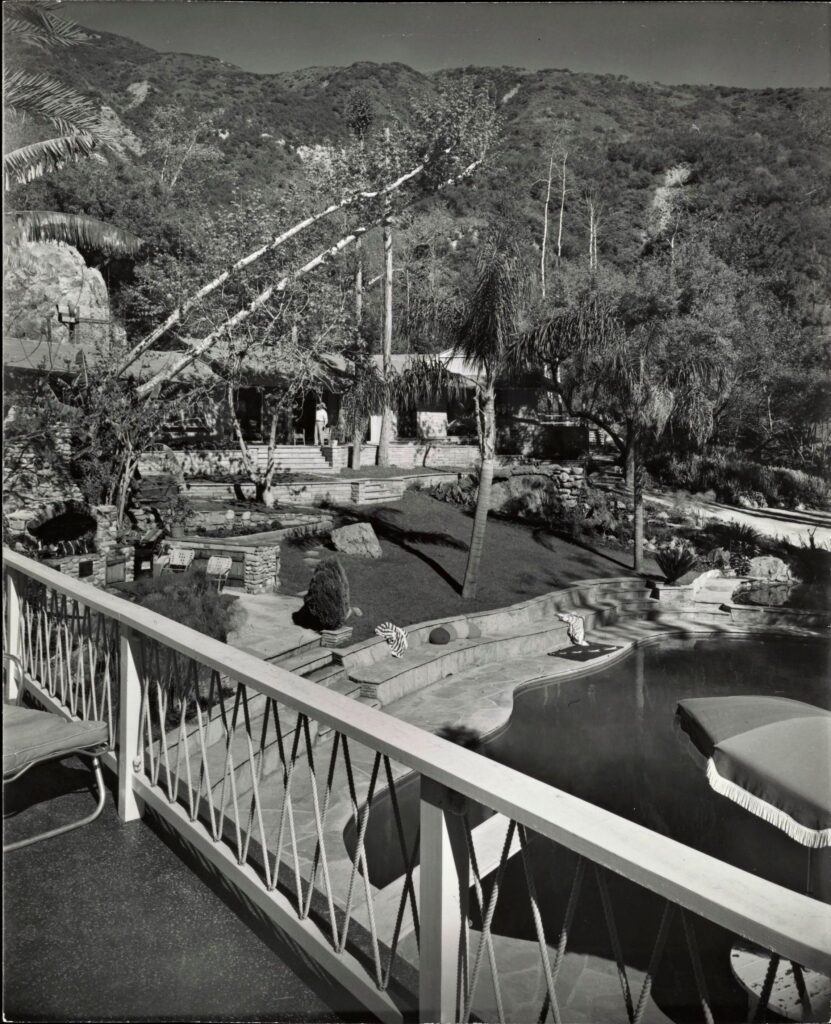

For the Roberts family in Malibu he created a canyon fantasy, with a waterfall outside the kitchen window, and a garden full of tropical plants. Fred Roberts, who founded Roberts Public Market in Santa Monica and developed a successful chain of grocery and liquor stores, bought 1000 acres in Solstice Canyon in the 1930s.

In 1952, Roberts and his wife Florence commissioned Williams to design a home for them that would blend naturally into the canyon’s environment of waterfalls, springs and trees. The house, built of stone, brick, and wood, was designed to frame the view and bring the outdoors inside, with the rooms arranged around a garden that featured a pool surrounded by lush, tropical vegetation, watered by abundant natural springs and suggesting a Hawaiian garden, instead of a dry Chaparral canyon.

Solstice Canyon is now part of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, and was one of the first properties in the area acquired by the National Park Service in the 1980s. The house burned in a major wildfire in 1982. The canyon burned again in 2007 and 2018, but the foundation remains, inviting visitors to walk up the gracefully curved stairs to a front door that exists only in memory and to enjoy the view that inspired the architect’s design.

The ruins of the house, nicknamed “Tropical Terrace,” are an easy walk on a mostly paved trail that was once the ranch road. It’s a great way to experience a lost chapter in local history, and to celebrate the life and legacy of a great American architect, and a Southern California legend.

“Paul Williams led by example and instilled in his children and grandchildren the importance of excellence, an attention to detail, and above all, family,” said Hudson.

“As the family historian, my journey has been one of awe and encouragement. Never once did I believe my work was my gift to him, for it has been, and will always be, his gift to us. To others he is often referred to as ‘the architect to the stars,’ to his grandchildren, he was simply the best grandfather ever.”

The archive preserved by Hudson documents Williams’ entire career, from his early residential commissions during the Los Angeles housing boom of the 1920s, to those landmark mid-century civic structures, and his later work in the 1960s. The plans represent the majority of Williams’ commissioned work, including projects that were never built.

“The work contained in this archive tells many stories,” said Milton Curry, dean of the USC School of Architecture. “It also contains evidence of stunning aesthetic innovations that reimagined the space and program of public housing, hotels, residential design and civic space.”

Curry explained that the Paul Williams Archive Initiative will be a central feature of the forthcoming USC Center for Architecture + City Design.

“Paul Williams was a trailblazing architect whose long career helped shape Los Angeles and Southern California, said Getty Research Institute director Mary Miller. “His archive essentially tells the story of how the modern Southland was built. Its importance as an aesthetic and educational resource cannot be overstated.”

Williams retired in 1973, having received numerous accolades, including the AIA’s Award of Merit for the MCA Building (1939) and the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal for his outstanding contributions as an architect and work with Los Angeles’s Black community (1953). He died in 1980, at the age of 85, and was posthumously awarded USC Architecture’s Distinguished Alumni Award in 2017.

The archive will be housed at Getty, which will oversee processing and conservation of the materials, which are in excellent condition, thanks to Hudson’s stewardship. An extensive digitization effort will take several years and will ultimately make most of the archive accessible to scholars and others.

“The collaboration of two such esteemed institutions, the University of Southern California and Getty Research Institute, to preserve and further his legacy, would make our grandfather extremely proud,” Hudson said.