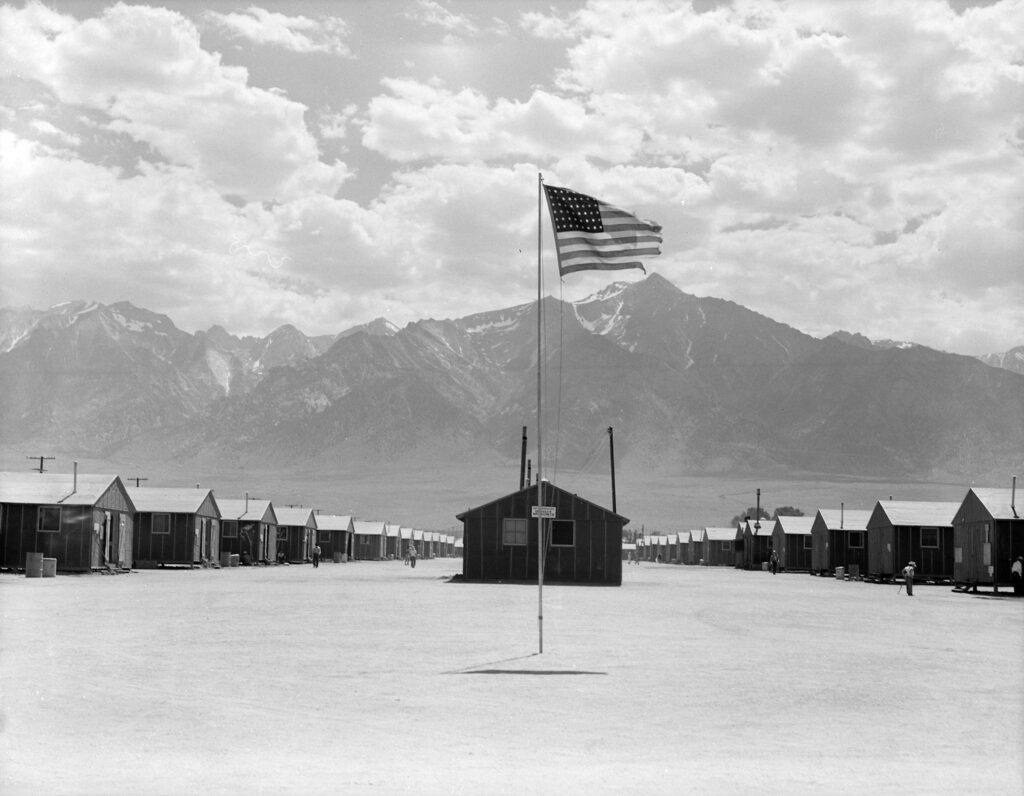

It’s a stark photo: a young man bending to drink from an Army canteen. Behind him is a vast empty landscape of desolate desert and forbidding mountains.

This is Masaro Takahashi, 19, a Malibu farm boy, one of a family of seven, and part of a group of one thousand Japanese Americans from Malibu, Santa Monica, and Venice, who endured three and a half years of hell at the Manzanar War Relocation Center. He was 18 when he arrived with his family, and 21 when he was finally released.

Masaro’s father, Kitaro Takahashi, emigrated to America shortly before World War I. He found a job in Westwood. Within a few years he was able to send home for a wife. His family in Japan arranged for him to marry Yoshie Hsaka. She was 11 years younger and traveled all the way to Southern California to marry a man she had never met. Although it was an arranged marriage, it was a successful one and they had a good life together.

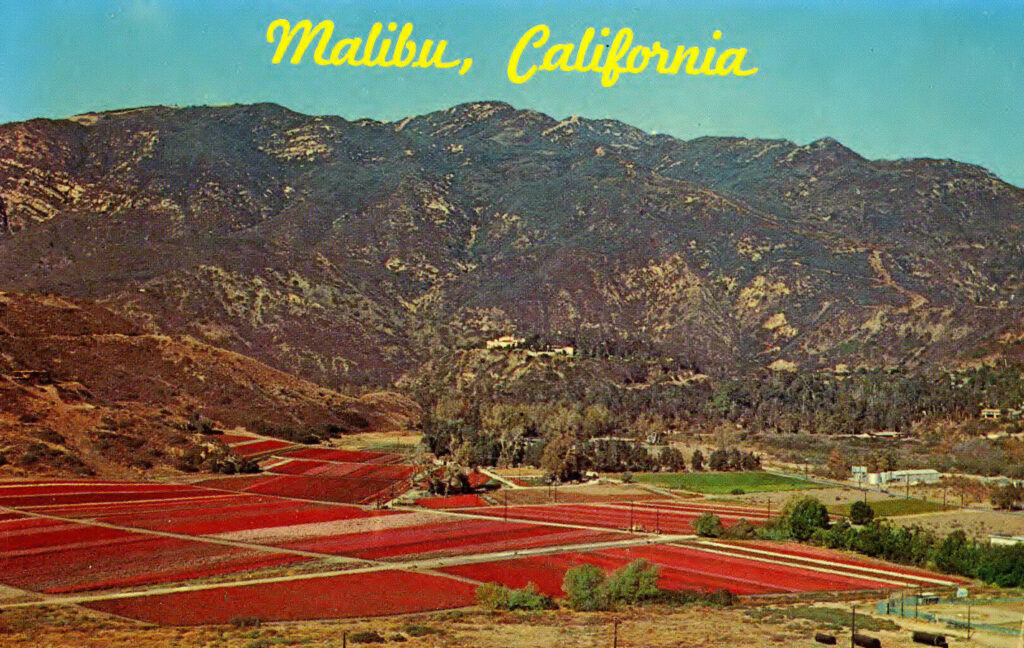

By the early 1920s, Kitaro and Yoshie had five children and were ready for a different life. They moved to Malibu, where they leased farmland from the Rindge family in the floodplain of Malibu Creek. The family worked together to raise crops like spinach, strawberries, and the colorful geraniums that would become a famous Malibu landmark.

Author and historian Craig Smith interviewed Masaro’s sister Mitsuie—Mitzi— Takahashi for his 2011 book Counting the Days: POWs, Internees, and Stragglers of World War II. Mitzi remembered life in Malibu as hard work but a generally happy time. The family weathered the Depression with enough food to eat and an optimistic attitude.

Mitzi and her twin sister Fumiye—Dorothy—rode the rattletrap old school bus into Santa Monica with the other ranch children. “I remember those were happy times,” she told Smith. “The bus windows open, our hair blowing in the breeze, the smell of the ocean and the sound of the surf as the old bus rattled along Pacific Coast Highway.”

Mitzi loved sports—she and her sister were on the basketball team in high school, and she dreamed of a future that didn’t involve milking cows and weeding crop rows. She had a job at a Los Angeles bank and a future to look forward to when she and her family were uprooted, imprisoned, and shipped to Manzanar.

Amy Takahashi Loki was the youngest member of the family. She was 16 when the family was sent to Manzanar.

“We lived in Malibu, I never felt any prejudice,” she recalled in a 2011 interview in the Malibu Times. “We all went on the same bus, day in and day out, and all became good friends.”

It didn’t matter that the Takahashi children had all been born in America, or that the family had never done anything wrong, they had just days to dispose of property and possessions and report to the corner of Venice and Lincoln Boulevards with just the things they could carry.

Many Japanese families were sent to a depot where they had to wait days or weeks or months before being sent on to a camp. The Takahashis and the other local families were put on buses and sent directly to Manzanar.

Because the Takahashis were a large family, they were allocated a room of their own. “If you were in a small family, they were put in a room with three other families. It was really like a concentration camp until they found out we were really harmless,” Amy said in The Times interview.

More than 112,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast were forced into concentration camps scattered across the country. Anyone with Japanese ancestry could find themselves stripped of their rights as a citizen and shipped off to a concentration camp. Even orphan children were viewed as a potential threat and sent to the camps. An estimated 80,000 of those who were incarcerated were second and third generation American citizens.

In 1988, when reparations were finally made for the survivors of internment, Congress acknowledged that the government’s actions in 1942 were the result of “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

That war hysteria and racial prejudice was driven by the actions of people like Los Angeles-area Congressman Leland Ford. He was the elected representative for a large population of Japanese Americans, but that didn’t stop him from being among the first to lobby for mass incarceration following Pearl Harbor. He demanded that, “all Japanese, whether citizens or not, be placed in [inland] concentration camps.”

Columnist Henry McLemore, a syndicated sports reporter for the Hearst Corporation, went even further: “I am for immediate removal of every Japanese on the West Coast to a point deep in the interior,” he wrote. “I don’t mean a nice part of the interior either. Herd ’em up, pack ’em off and give ’em the inside room in the badlands. Let ’em be pinched, hurt, hungry and dead up against it . . . Personally, I hate the Japanese. And that goes for all of them.”

Manzanar delivered everything on McLemore’s wish list. It was bitterly cold in winter and mercilessly hot in summer. The camp was crowded and there were no comforts and few necessities.

“We sat on the floor and it was cold,” Amy recalled in the Malibu Times article. “No books, and the teachers were very young and probably just starting. Who would come out to a place like that if you were a good teacher?”

The prisoners developed their own classes and programs and forged a community out of adversity.

Members of the Takahashi family were able to return to Malibu after the war and resume farming, eventually acquiring the acreage they had previously leased. Longtime residents still remember the dreamlike fields of scarlet and pink geraniums grown by the second and third generation of the family from the1950s to the early 1970s.

Amy finished high school at Manzanar and went to work in the camp hospital. She would go on to become a medical stenographer, but throughout her long life she remained in close contact with the friends she made during the ordeal of internment. It was through that shared experience that the Venice Japanese Memorial Marker was created. More than 70 years after internment, a handful of the survivors came together to create a lasting memorial for the local Japanese American community.

The black granite marker stands on the northwest corner of Venice and Lincoln, at the place where the families were forced to gather on that day in April 1942. The monument has all of the names of 1000 residents, but it also is inscribed with quotes from some of the survivors, including Amy. Her message states:

“As a 16-year-old I didn’t realize the injustice fully, but in time we learned how our rights as citizens were ignored. Thanks to the strength and resilience of our Issei [first generation] parents, we were able to survive.”

Emiko Amy Takahashi Ioki died on June 4, 2020. She was 95. Part of the property that her family farmed in Malibu is still known unofficially by her married name, Ioki. The City of Malibu acquired the 9.65 acre Ioki property in 2018, with the intention of using it for community amenities. Whatever those plans ultimately are, the history connected to the site and the family that lived there will not be forgotten.

The official day of remembrance is February 19, the 79th anniversary of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, which authorized the incarceration of Japanese Americans during WW II.

To learn more about the Venice Japanese American Memorial, visit https://venicejamm.org

The Manzanar War Relocation Center in the Owens Valley is a National Historic Site. It is currently closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, but a place all Californians should visit: https://www.nps.gov/manz/index.htm