I stopped on a Topanga road the other day to wait for a chicken to cross. It gave me a moment to reflect that before asking why it crossed the road, it might be helpful to know why the road was there in the first place, who built it, and how. In Topanga, the answer is often complex and multilayered.

Long before European colonists arrived, the mountains were traversed by the Tongva and Chumash people and their ancestors, who lived in this area for millennia. Carbon dating of sites show proof of human activity for at least 5000 years.

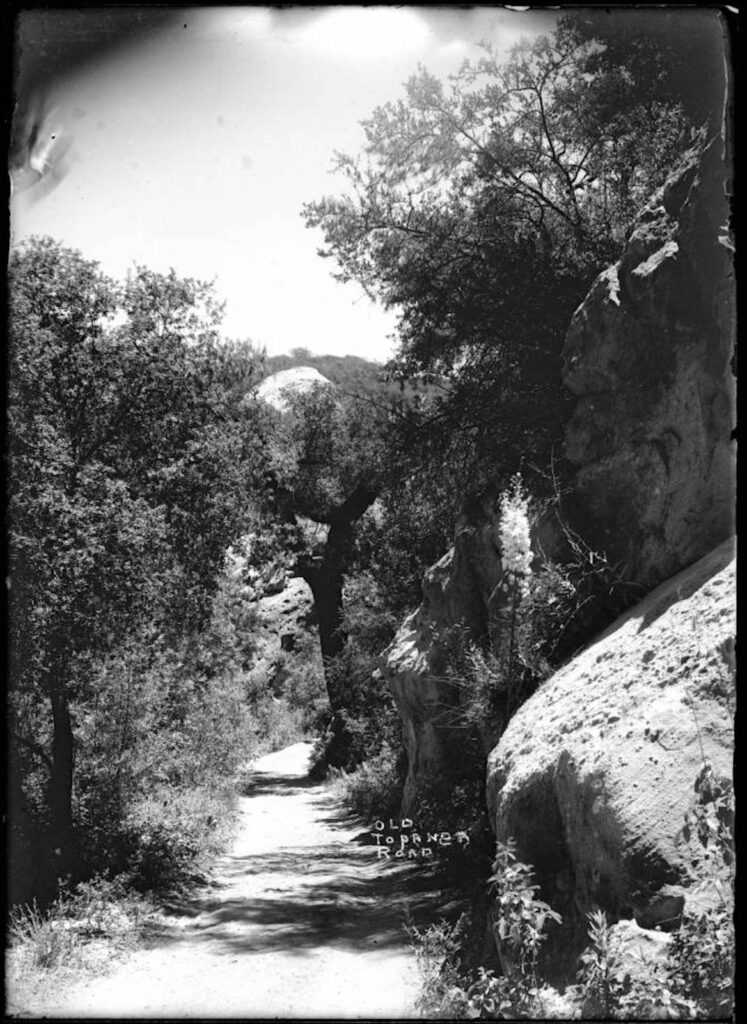

When the Spanish colonized the area in the late eighteenth century, they accessed Topanga on the route that is now Old Topanga Canyon Road. It’s located just off El Camino Real, the main route up and down coastal California that was established by the Spanish missionaries.

The biggest influx of homesteaders arrived in the Topanga area after the U.S. government’s Land Act of 1862, which opened surveyed public lands to anyone who could stake a claim and hold onto it. This wave of settlers accessed Topanga by the same route. Anyone who wanted to travel all the way down to the coast had to pick their way through the canyon on a trail barely wide enough for a horse cart.

That changed in 1893, when plans to build a port for the city of Los Angeles just west of Santa Monica generated a frenzy of road work that resulted in a stagecoach route from Calabasas to the sea. Even then, a trip down the mountain to the coast route and into Santa Monica was an all day adventure, one that often couldn’t be undertaken in winter when the road washed out.

It wasn’t until the automobile craze in the first years of the twentieth century that an improved road all the way through the mountains from the valley to the sea was planned. And the plan wasn’t in response to the needs of the residents, but was for the pleasure of the wealthy new class of automobile enthusiasts, who longed for adventure but also wanted to be home in time for supper.

The Auto Club was founded in Los Angeles in 1900 by some of the burgeoning city’s most influential and important citizens. The club quickly became a motivating force behind the evolution of California’s car culture and the state’s extensive network of roads.

The push for a valley-to-sea Topanga car route included a series of high profile, illustrated newspaper features. One 1908 article in the Los Angeles Times boasts that a party of 15 automobiles drove through Topanga with “only one punctured tire between them.”

The expedition was organized by Colonel F. C. Fenner, owner of the White Garage, who “wished to show owners of White cars that there are many little known and delightful runs around Los Angeles.”

The article was a puff piece for White’s business, which sold steam-powered vehicles. Fenner was a colorful character who owned the legendary Big Horn Gold Mine near Wrightwood, in addition to his car dealership. He was also a passionate cross county race car driver, achieving dizzying speeds of up to 50 mph under full steam. His 1905 White Model E steam car, named “Black Bess,” is still being driven.

Fenner’s perspective on road hazards was probably somewhat different from those of a casual town motorist, but the goal was to reassure and encourage motorists to take to the road.

“The road through Topanga Canyon is not very often traveled by motorists, and various stories have been told of the difficulties of the route,” the author enthuses. “The run yesterday demonstrated that there are few places where an automobile cannot go, and probably dispelled the fears of many motorists.”

A constant stream of articles, features, and society photos showed motorists driving steam, electric, and gas powered automobiles through the creek, balanced on boulders above the road, camping under the oaks, or even broken down on the side of picturesque ravines. A 1910 article in the Los Angeles Times features a gentleman fishing for trout in Topanga Creek without leaving the comfort of his car.

“The automobile was driven up and down Topanga Creek and the shallows whipped without leaving the machine” the article boasts.

The fact that there wasn’t an official, dedicated right-of-way, and that motorists were traveling through homesteads and in the stream bed was conveniently left out of these thrilling accounts of motoring adventure.

Topanga residents appear never to have been asked whether they wanted a road or where they thought it ought to be built, but they moved with the times, setting up campsites in their fields and orchards, cooking meals for travelers, and helping to pull vehicles off the road when they broke down.

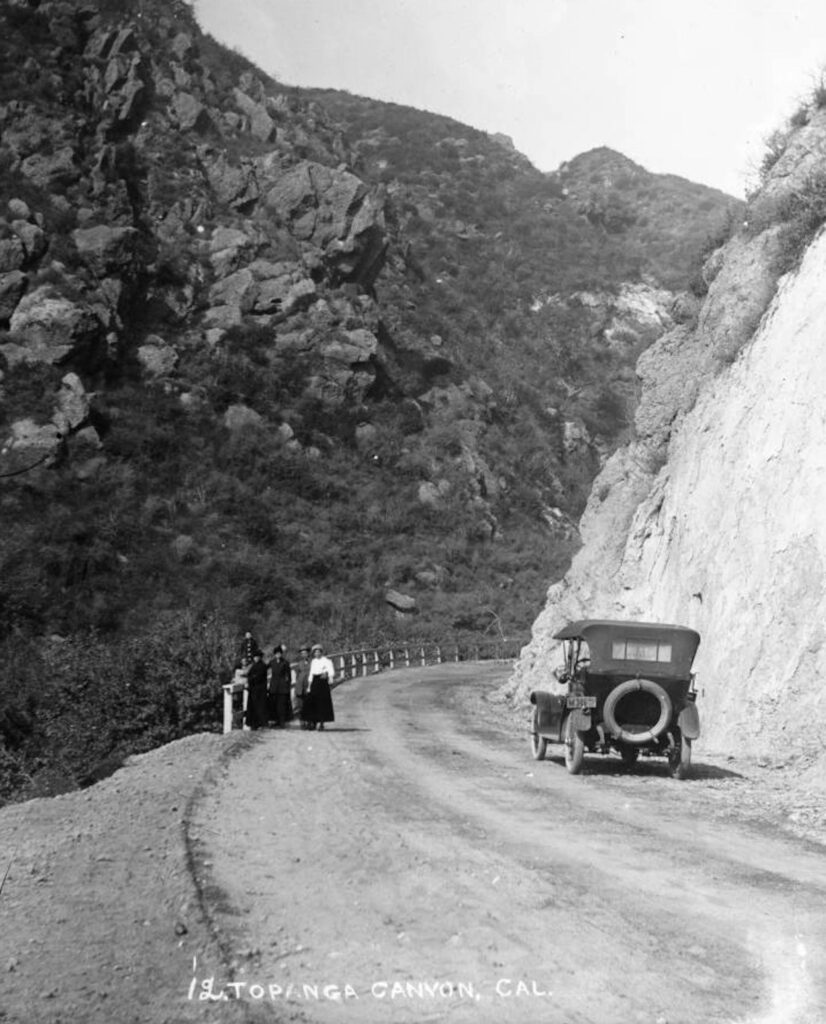

Road improvements were made as car culture continued to explode in popularity. The road was widened and paved with oil-treated gravel to keep the dust down, but the route still wound precariously up the canyon and through Old Topanga in what was little more than a single track.

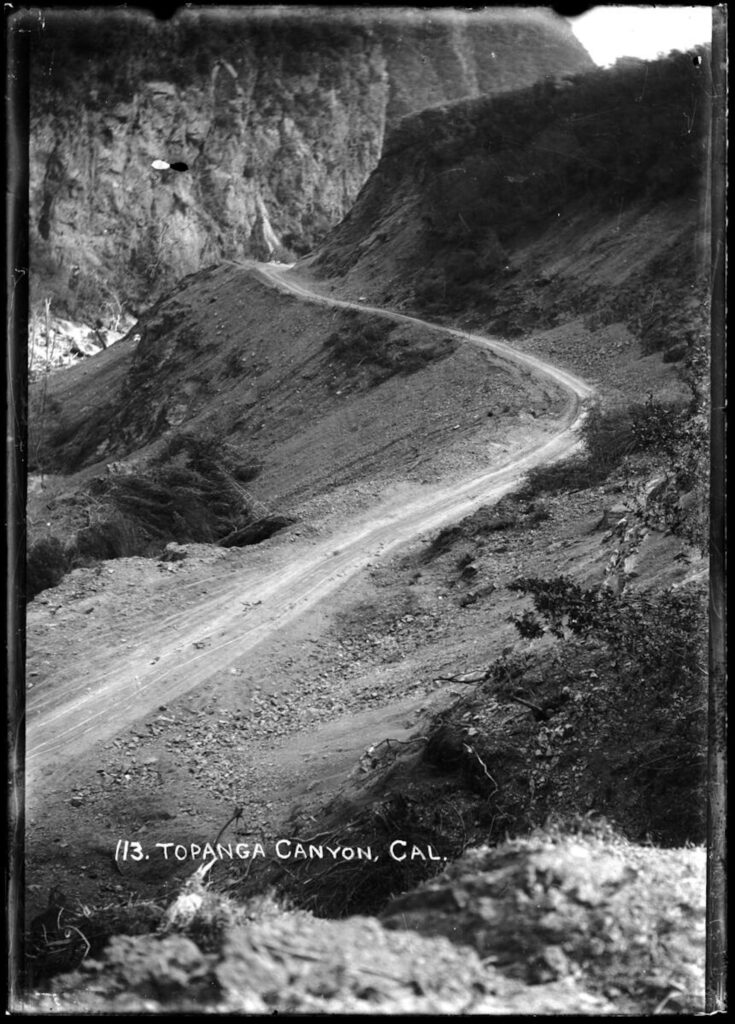

The Auto Club began promoting a drive called “The Big Oval.” It began on Washington Blvd. in Venice, traveled down the coast route to Topanga Canyon, over the mountains to what is now Owensmouth, and from there to Van Nuys Blvd. and back to Los Angeles through the Cahuenga Pass. Despite the glowing descriptions, the road through Topanga was sketchy at best, a perilous mix of steep grades, narrow dirt track, and frequent rock falls. The Auto Club lobbied for a new route over the summit, but the request was repeatedly rejected by the county. The proposed road was too expensive; the engineering it required, too extreme.

In 1912, the Los Angeles Herald proclaimed that the Auto Club had solved these problems on its own, negotiating the right of way with canyon homesteaders, organizing the $700 needed to complete a survey, and even hiring an independent engineer to design the route.

“Motorists are assured by the Automobile Club that if the present good weather continues work can be rapidly pushed and the automobile road of the Topanga canyon route will shortly be completed,” the article concludes.

The club’s secretary, identified only as “Miss S.C.”, states that the Automobile Club “has finally solved the problem of the heavy grades to be found in this part of Calabasas,” and that the solution involves a 7% grade down previously privately owned property, “making it possible for any car to make this beautiful trip with ease.”

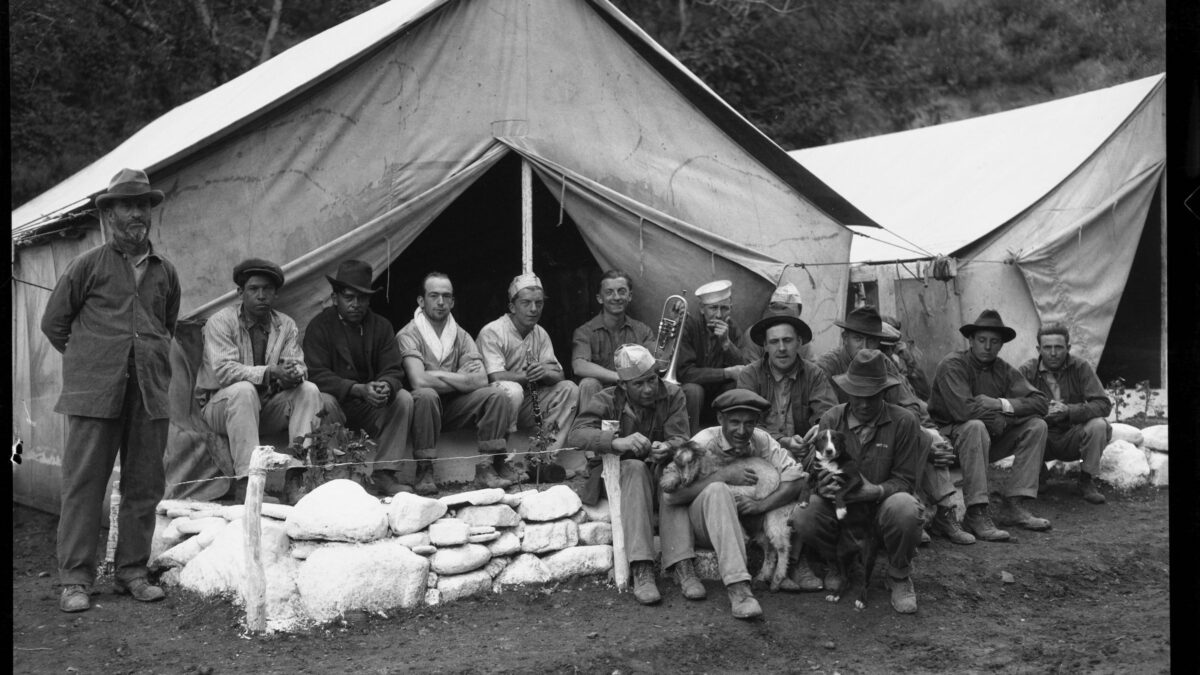

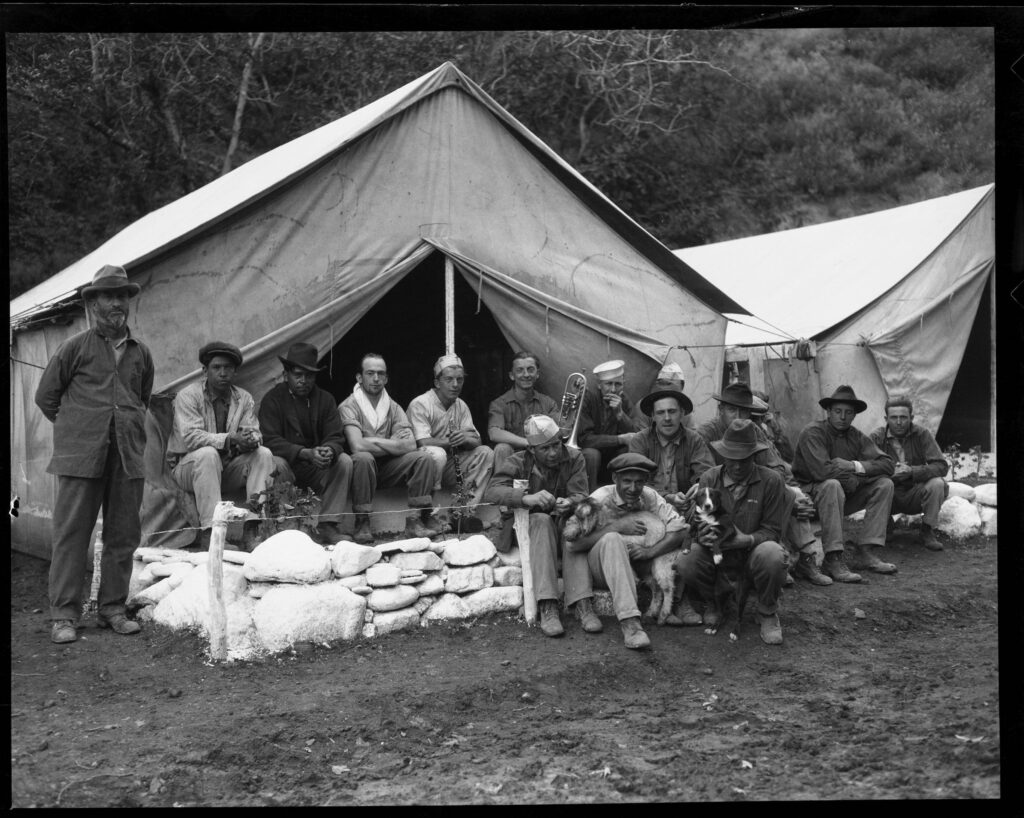

The announcement assured the public that “the actual work of construction is to be done by convict labor, thus enabling the total expenditure for the opening of the Topanga route to be made an exceedingly nominal one.”

Los Angeles County Supervisor P. W. Pridman told The Herald that the county was “ready to have the convict labor begin work immediately.”

Earlier prisoner road crews worked on the Old Topanga Canyon stagecoach route. The prisoners working on this project carved out that seven percent grade from the mountainside with hand tools, mules and dynamite. It was hard work in dangerous conditions, even in good weather. The road took nearly three years to complete. The Auto Club celebrated with a parade and picnic in May 1915.

Today’s motorists still travel the route built by convict laborers more than 100 years ago, a route that was first traveled by the canyon’s original inhabitants 5,000 years ago, and used in the eighteenth and nineteenth century by colonists, homesteaders, and cattle rustlers. It crosses land that not all that long ago was home to livestock and crops and cuts through rock that was formed on the floor of an ancient ocean.

And despite the Auto Club’s century-old assurances that once the road was improved, the trip through the canyon could be made “with ease”, this is still a challenging road: narrow, winding, prone to rock slides, mudslides, downed trees, accidents, and even the occasional chicken. Some things never change, which is just how most residents of Topanga have always liked it, even if the road planners and the road builders never thought to ask.