Best-selling and award-winning writer Jess Walter has produced seven novels. Depending upon the order in which they are read, it seems that one might have to consume four or five before daring to speak with any clarity regarding the type of author Walter is.

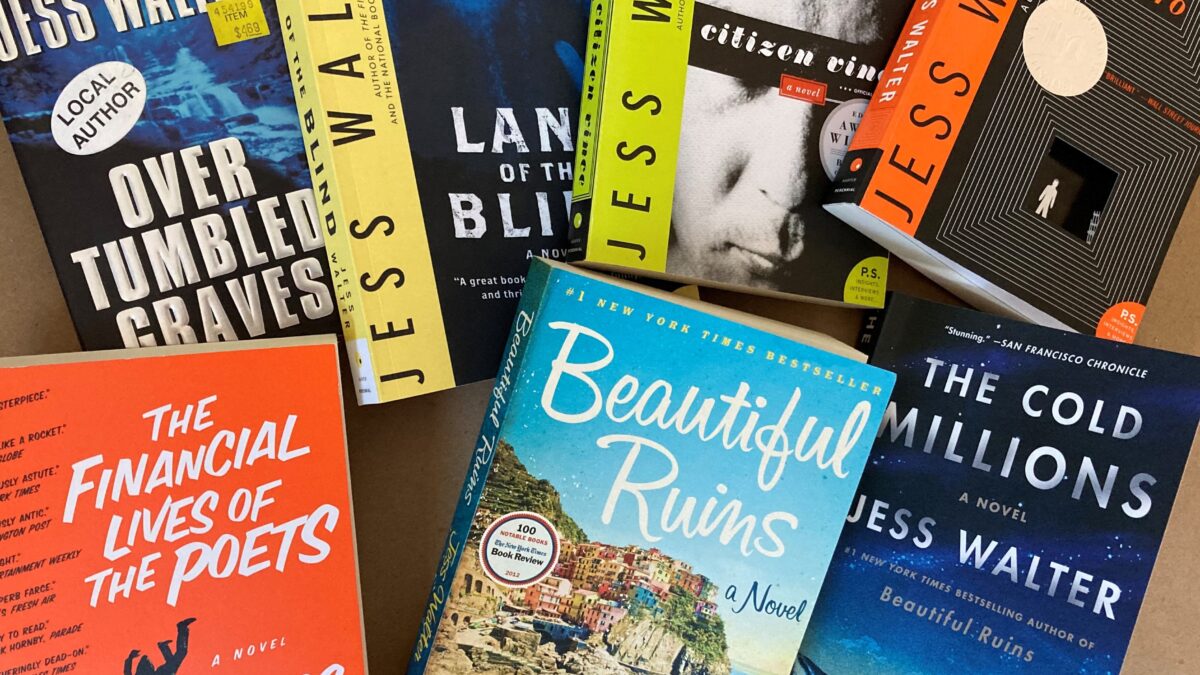

Perhaps something can be gleaned from what seems an outlier. Unlike his later work, Walter’s first novel, Over Tumbled Graves, has a familiar plot and a chronologically ordered storyline: troubled Spokane, Washington police Detective Caroline Mabry hunts down a serial killer. It’s a great thriller. My tattered and browned paperback copy includes props from James Patterson and a Local Author sticker is on the cover.

The commercial success of this first novel—set in Walter’s childhood and current home—seems to have inspired the confidence to take some risks. For instance, it is revealed in the second paragraph of Jess Walter’s second novel, Land of the Blind (2003), that a mysterious vagrant wears a black patch over his left eye and it is wickedly obvious that the entire story to come revolves around that patch. I learned later that Walter is left-eye-blind.

In a shift not usually found in a book series, Land of the Blind introduces a burgeoning fan base to the author’s ability to flawlessly weave together seemingly disparate stories. In this case, Detective Mabry is compelled to take the late Friday night confession of a “murderer” despite the absence of a victim. “The Loon”— as she calls him —is disheveled and unkempt. A first glance indicates homelessness while a second has Mabry swooning a bit; at least enough to hear him out.

The one-eyed stranger insists, though, that a proper telling must be written down.

Over the next 48 hours, the story unfolding on paper parallels Mabry’s own; one marked by the heaviest of burdens borne by those who have made a fatal mistake… a conscience.

So, the first Mabry thriller follows a familiar script while the second unleashes the nuance of multiple plots and the dazzling word construction that will become the hallmark of a Jess Walter novel.

Also set in Spokane, Citizen Vince (2005) features another troubled soul struggling to make peace with his past. Vince Camden is in a witness protection program and decides that he wants to come clean with the seedy mobsters he has betrayed.

Set during the run-up to the 1980 presidential election, Vince’s conscience is stirred after receiving a voter registration card. For the first time in his life, he imagines himself a citizen while reluctantly embracing his made-up identity as a fresh start. If he is to be true to himself, however, he must own his past.

Parallel to Vince’s personal story is an America debating what type of country it wants to be; at least to the degree that our president reflects who we really are (scary thought, I know). In this case, Citizen Vince suggests that promoting a Hollywood B-Movie star to the White House in 1980, with the “moral majority” in his back pocket, might not paint a picture many of us want to look at. And, if you recall, we rejected for a second term perhaps the nicest guy who has ever held the office.

In perhaps the defining moment of the young twenty-first century, Walter’s The Zero (2006) refers to Ground Zero and the lives that were lost on 9/11. And, in this case, the numbers far exceed those that physically perished on that fateful day to include the uncounted victims sentenced to remain among the living while pondering the cruelties of chance.

The Zero destroys the myth that the events of 9/11 brought us all closer together. The reality is that we waved flags for a few minutes and then retreated back into our tribal bubbles.

Brian Remy is a traumatized cop who is celebrated as a hero simply for the fact that he was present when the towers came crashing down. In a brilliant—and what I can now safely call—“Walterian” move, Remy suffers from repeated memory gaps. As he jumps from scene to scene almost clueless as to what is happening around him, his confusion is viewed as wisdom. His straight-forward questions become philosophical testimony. The message is that we all live in a world where actual wisdom and spiritual insights are indistinguishable from all the info-garbage flowing through our lives.

More social commentary is found in The Financial Lives of Poets (2009) where the myth of middle class America is exposed amid the financial and housing crisis of 2007-2009. Walter reminds us that the propaganda we feast upon has worked its way into our DNA and that we all live lives on the verge of collapse totally oblivious to the lessons of even our most recent history.

Next up is Beautiful Ruins (2012), a wonderful mosaic spanning 50 years with complete and brilliant disregard for chronological order. Beginning in a tiny village on a rocky Italian shoreline in 1962, we once again travel back and forth in time and space. Subtle hints are dropped before the many narratives are snapped into place.

Drawn back to his hometown in his most recent novel, The Cold Millions (2020) is inspired in part by the actual labor history of the early twentieth century. Featured is a nineteen year-old and pregnant Elizabeth Gurley Flynn who, in 1909, was just beginning more than half-a-century defying gender norms while fighting for workers’ and women’s rights.

Spokane in 1909 is a hardscrabble environment where efforts to organize a massive single labor union are met with all the power that railroad, banking, and mining money can muster. The filthy rich live on South Hill while the masses struggle to feed and house themselves; not completely unlike the Spokane (America) of Walter’s day.

The sixteen year-old protagonist in The Cold Millions is Rye Dolan who hasn’t had much schooling but knows enough about the world not to be fooled by all the rhetorical nonsense: “And the idea that you could make men equal just by saying it? Hell,” he thinks, “it took only your first day in a Montana flop or standing over your mother’s unmarked grave to know that equal was the one thing all men were not. A few lived like kings, and the rest hugged the dirt until it cracked open and took them home.”

There’s a lot more where that one came from. Enjoy.