Black History Month is tricky. One month a year dedicated to recognizing the contributions and struggles of black Americans seems harmless enough. However, as a set-aside to the larger epoch of America, singling out an ethnic group in this manner suggests that this “extra” history simply runs parallel to the “standard” history of the country.

Unfortunately, this superficial interpretation of Black History Month has been adopted by those who believe that periodically posting an “I Have a Dream” quote demonstrates open-mindedness and a commitment to diversity. This is especially troubling among those whose day-to-day behaviors underscore a short-sighted patriotism with a field of vision that excludes black history as it was actually experienced by black Americans.

The antidote to this myopia? Good black history; starting with the harsh realities of American slavery and its role in forging our nation.

First imagined as The 1619 Project from The New York Times Magazine, Nikole Hannah-Jones and other Times writers have caused quite a stir; which is exactly what they intended to do. Situating the nation’s founding from the arrival of “20 and odd Negroes” to Virginia in 1619 is nothing less than an effort “to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans at the very center of the United States’ national narrative.”

First published as a series of articles in August of 2019 in the quadricentennial commemoration of the first enslaved Africans arriving in English America, “1619,” as a date and the marker of an idea, conceptualizes the tenacious dialogue taking place between those seeking an honest reckoning with our nation’s past and those whose impressions of history are largely limited to the experiences of those whom they resemble.

As in other moments when African Americans have asserted themselves, much of the story is best understood through the white backlash it provokes.

In the current uproar, a single comment sums up the conservative campaign to discredit the promotion of good black history. In opposition to a school curriculum being developed around The 1619 Project, Arkansas Republican Senator Tom Cotton recently said of slavery, “As the Founding Fathers said, it was the necessary evil upon which the union was built…”*

Necessary to achieve what, Tom?

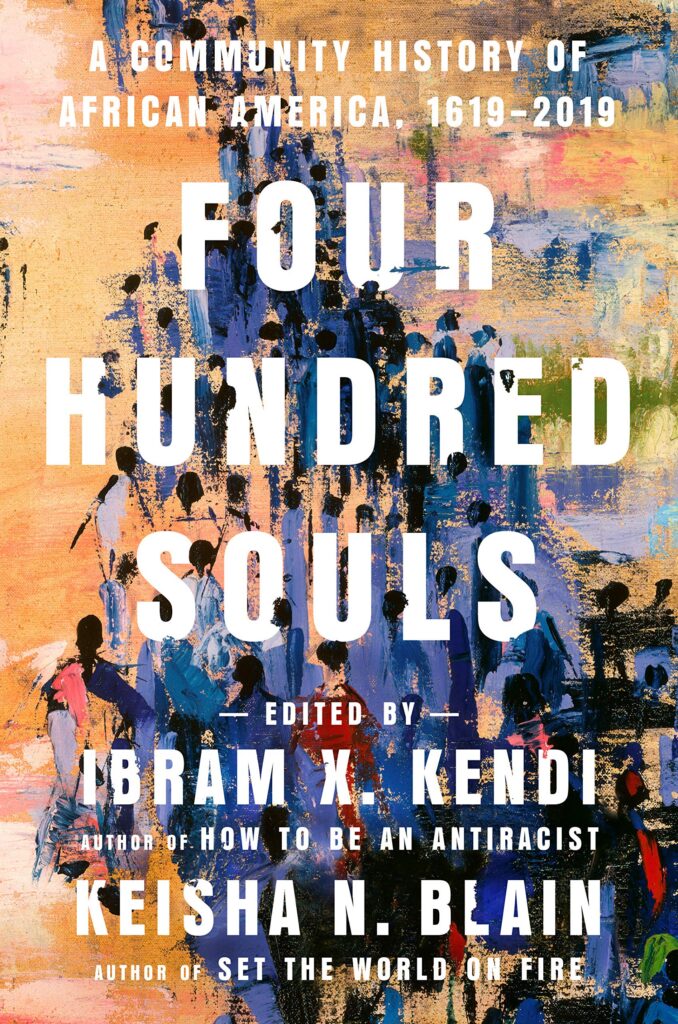

If you would like to immunize yourself against ignorance such as this, I suggest you take a look at Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019 (2021), edited by Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain. Eighty different writers—“a choir of black voices”—were each tasked with commenting upon a five-year span of the 400 year scope of black American history. Beginning with 1619-1624 and then 1624-1629 and eventually 2014-2019, this wildly diverse collection of essays, sketches, articles, and brief histories sheds the light the creators of Black History Month imagined.

In “Arrival” (1619-1624) Nikole Hannah-Jones compares the historical treatment of the arrival to the New World of two ships; the White Lion in 1619 and the Mayflower in 1620. Everyone is familiar with the Mayflower while the story of the White Lion was conveniently omitted from history as its cargo included those “20 and odd Negroes.” Thus began the very intentional selectivity of American history.

With that in mind, it becomes easier to imagine modern efforts to portray the origins of American slavery as incidental to the times and something colonialists adopted as a matter of the natural order of things. Unfortunately, this narrow thinking belies the historically documented religious and political tools brought to bear to establish and sustain the institution.

In “The Black Family” (1649-1654) Heather Andrea Williams presents an effort by black parents to secure their child’s freedom by arguing to officials that he had been baptized and raised as a Christian. After scores of children gained their freedom in this way, white Christians saw the potential threat to their labor supply. By the early 1700s, these “loopholes” were slammed shut.

As Jemar Tisby writes in “The Virginia Law on Baptism” (1664-1669), “white Christians deliberately retrofitted religion to accommodate the rising racial caste system.”

In “The Virginia Slave Codes” (1704-1709) Kai Wright explains that American slavery was not the benign adoption of an existing structure. “In reality,” Wright states, “colonial legislatures consciously conceived American chattel slavery at the turn of the eighteenth century, and they spelled out its terms in painstaking regulatory detail.”

“The past,” Kai Wright added, “is filled with people who carried out evil acts with foresight and determination, supported by the complicity of their peers… White supremacy became the norm in America because white men who felt threatened wrote laws to foster it, then codified the violence necessary to maintain it.” And then they put their actions to paper in a manner that suited their own purposes.

Wright dramatically exposes the harsh intentionality of the institution of slavery: “The myths Americans tell themselves [today,] that people did bad things out of ignorance rather than malice, that the good guys won in the end—encourage a false faith in the present.” And, when we engage with history, it is the present we are most concerned about; for it is within the present that the lies of the past are promulgated.

Perhaps the most pernicious of these is the ludicrous notion of African docility. Several contributors to Four Hundred Souls speak to this thoroughly debunked myth; that the enslaved enjoyed being cared for, saw their enslavers as family, and had not the slightest inclination to flee.

A proper reading of black history reveals that resistance among the enslaved was pervasive; and all that need be done to confirm this is to examine the behavior of their white enslavers. The enslaved were prohibited from gathering together, and prohibited from learning to read and write. The Bible was presented as divine affirmation of their condition of servitude. Punishment and the threat of punishment were necessary to maintain control.

In “Denmark Vesey” (1819-1824), Robert Jones Jr. recounts one of many examples of violent resistance to enslavement. Vesey, a free black, organized a slave insurrection in Charleston, South Carolina after realizing that the blacks greatly outnumbered the whites. He recruited “as many as nine thousand Black people under the single banner of their own liberation…”

In many more stories such as these in Four Hundred Souls, black history is well-served while 1619 claims its rightful place in the genesis of our nation.

*Cotton later claimed that he was just sharing what others said back-in-the-day even though there is absolutely no evidence that any of the Founding Fathers said anything of the sort.

https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/27/politics/tom-cotton-slavery-necessary-evil-1619-project/index.html