Pacific Palisades is celebrating its centennial this year. However, when the first Founders Day was celebrated on January 14, 1922, this area already had a long and colorful history. The first officially recognized archeological site in Los Angeles County is located between Topanga and Pacific Palisades. CA-LAN-1 was first excavated in 1947. Topanga Canyon was the boundary between the Tongva and the Chumash. The site provides some insight into the people who would have first settled the Pacific Palisades area. Organic material from the site has been carbon dated to 6000 years BCE, but the ancestors of the Tongva people arrived around 10,000 years ago.

During colonization, the Tongva were forced into the missions at San Gabriel and San Fernando. The land that would become Pacific Palisades was mostly uninhabited when it became part of the Rancho Boca de Santa Monica Mexican land grant in 1839.

The 6,656-acre grant was awarded to Francisco Marquez and Ysidro Reyes. It included parts of what would become Brentwood, Santa Monica, and Topanga, as well as Pacific Palisades. The families thrived, despite a longstanding dispute over the boundaries of the rancho with the neighboring Sepulveda family, who were awarded an overlapping land grant the same year—the 33,000-acre Rancho San Vicente y Santa Monica.

All three families maintained their land during the tumultuous transition from a Mexican territory to a U.S. state, but as Los Angeles began to grow there was less demand for cattle and more for undeveloped land.

In 1872, an entrepreneur named Robert Symington Baker bought the Rancho San Vicente y Santa Monica. The following year, he purchased an undivided one half share in the Rancho Boca de Santa Monica—2,112 acres. He paid Ysidro Reyes’ widow Antonia $6,000 for the land.

Baker came to California in 1849, hoping to strike it rich in the gold rush. He didn’t find gold, but he made a fortune fleecing the other miners—literally. He sold them wool clothing and other supplies at exorbitant prices. With the money he made, he began investing in ranch land. By the time he set himself up as a real estate tycoon in Southern California, his ambitions extended far beyond wool.

In 1875, Baker married Arcadia Bandini de Stearns, cementing his position as a major player in the Southern California real estate boom. Arcadia, the wealthiest woman in California, was the widow of the fabulously rich Abel Stearns, the single biggest landowner in California history. She was also an heir to the Bandini fortune, and a formidable businesswoman.

Baker and his wife joined forces with Nevada Senator John P. Jones, who had recently invested in silver mines near Independence, Inyo County, California, and aspired to build a railway line to connect his new investment to the coast.

Jones, who was born in England and raised in Ohio, also came to California for the gold rush, but ended up making a fortune in the silver mines of Nevada instead, where he went on to become a county sheriff and then a five-term senator.

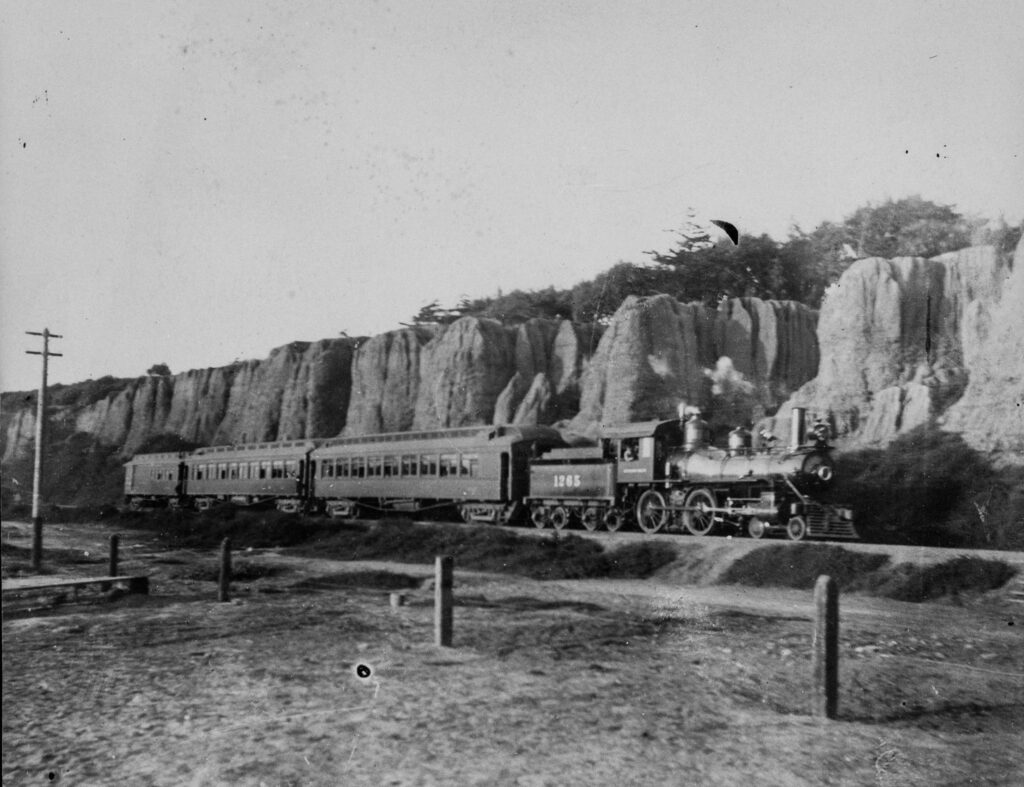

Baker sold a three-quarters interest in his newly acquired land to Jones for $162,500. They worked together to design the city of Santa Monica, with input from Arcadia—who is said to have given the city its name. They had plans for a major shipping port and railroad terminus that would be served by their own, newly incorporated Los Angeles and Independence Railroad, but railroad behemoth Southern Pacific didn’t appreciate being cut out, and began pressuring the would-be railroad barons.

Tracks were laid and the first building lots in Santa Monica were sold in 1875, but growth was slow, and the port project was delayed by financial difficulties. Baker and Jones, seeing their dreams of becoming shipping magnates slipping away, sold to Southern Pacific in 1877.

Baker turned to other projects, including the court proceedings required to divide his shares of Rancho Boca de Santa Monica, but he seems to have lost interest before the process was complete. He sold his remaining land holdings to his wife and partner and quietly faded from history.

Baker died in 1894. He remains something of an enigma. Surprisingly little is known about his life, not even how or when he earned the rank “Colonel,” or if that rank was real or just part of his image. He was 23 when he headed west to strike it rich in the gold rush, and 68 when he died in May of 1894 of “rheumatic diathesis.” In the 1870 census he listed his profession as “capitalist,” and that’s probably the perfect epithet.

Arcadia Bandini de Stearns Baker and John Jones founded the Santa Monica Water and Power Company together and continued to develop Santa Monica. Jones also pursued the partition of Rancho Boca de Santa Monica.

Ernest Marquez is the ultimate authority on the rancho. He is a descendant of the Marquez family and has spent a lifetime studying local history. In his book Rancho Boca de Santa Monica, he describes the arbitrary process used to divide the rancho, a process that resulted in Jones receiving the most valued portions of the land. Even Jones recognized the blatant unfairness of the decision. Ernest Marquez quotes a letter in response to that fleeting moment of conscience, and notes that Jones didn’t feel bad enough about it to actually do anything to make amends. The Marquez family fared slightly better than the Reyes heirs. They retained at least some of their land in Santa Monica Canyon, a place that had become a destination for holiday makers.

Pascual Marquez saw the potential in tourism and built bath houses and tent cabins that made it easy for modest Victorian-era beachgoers to enjoy sea bathing. An inn was built in the canyon as early as 1872. Charles Warren, the editor of the Evening Outlook and author of the 1934 book The History of the Santa Monica Bay Region, unearthed an ad for the establishment: “A week at the beach will add ten years to your life.” Warren quipped that the proprietor “set the pace in enthusiastic advertising for all of his successors in Southern California.”

Historical Society

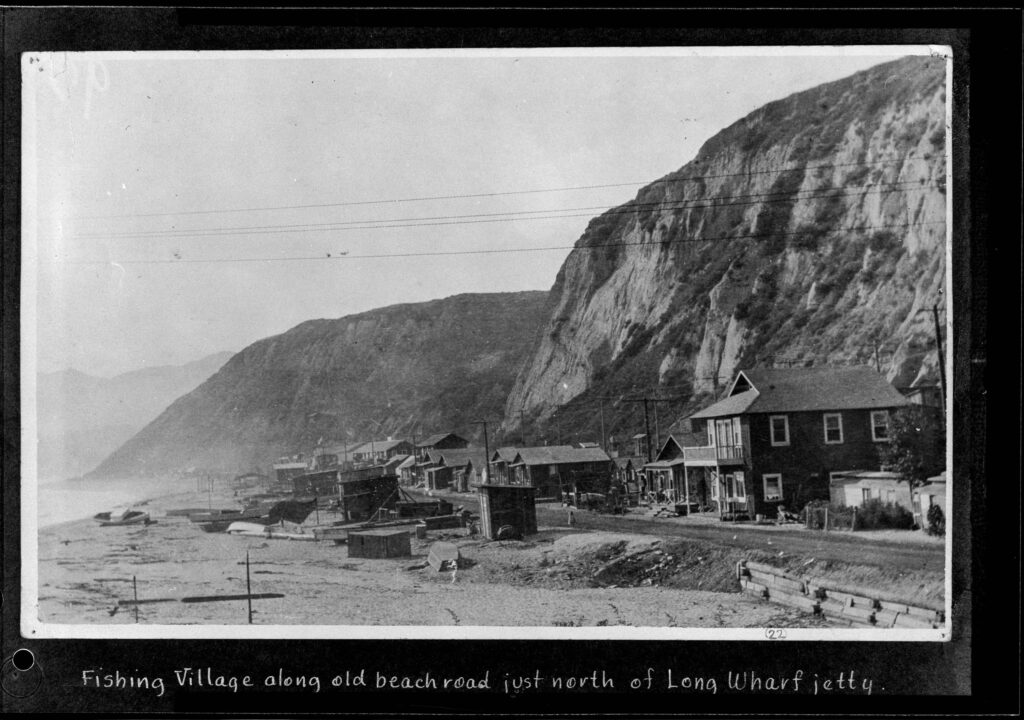

The family built cabins and a campground and quickly adapted to catering to a new class of visitors—motorists. The popularity of the area exploded when Southern Pacific began work on what was planned to be the official port of Los Angeles. The location chosen was between Temescal and Santa Monica Canyon. When the mile-long Long Wharf opened in 1894, this stretch of coast became a short-lived metropolis.

A Japanese fishing village quickly became home to at least 500. The shore was lined with warehouses, boarding houses, and bathhouses, tents and hotels, but ultimately San Pedro was chosen for the official Port of Los Angeles, and the Long Wharf was abandoned.

The Santa Monica Land and Water Company sold the land that would become Pacific Palisades to developer Robert Conran Gillis in 1904. It was an optimistic time: The Long Wharf was at its peak—it served as a cargo and passenger port until 1913—and the future looked bright, but the boom didn’t last. Gillis sold 1,100 acres of the land to the Pacific Palisades Association in 1921, the year after the last section of the decommissioned wharf was demolished.

Methodist Minister Charles H. Scott, the president of the association, had a vision for a religious and philosophical utopia. He planned churches, lecture halls, and a Christian education center, “the Chautauqua Institute of the Pacific.”

Pacific Palisades was purchased using a subscription system to raise the funds. Nearly 200 of the original 275 members paid $1,000 each. Additional investors bought in—membership in the church was not required. The association raised more than a million dollars in less than a year. On “Founder’s Day,” each of the original investors received a 99-year lease on lots chosen by lottery. By June of 1922, 725 of the original 1,600 lots had been sold.

“From my childhood it has been my chief ambition to see established in Southern California a religious and educational center that would be a credit to the Southland,” Scott told the Los Angeles Times.

The new community also began attracting some high profile residents who sought privacy and space. They included Will Rogers and Mary Pickford, who became early advocates for preserving what is now Topanga State Park.

For the rest of the decade, Scott’s vision appeared to be realized. Crowds gathered for inspiring sermons. There were concerts and music festivals, philosophical conferences, but the Depression brought an end to Scott’s utopian vision, at least until the beginning of WW II, which brought an influx of new inspiration and creativity from Jewish and anti Nazi German emigrés. They included author Lion Feuchtwanger and his wife Marta and Nobel Prize laureate Thomas Mann.

Development exploded in the post WWII boom years, covering the remaining mesas with a mix of housing tracts and custom houses, including some mid-century architectural gems. Property values have soared, but Scott’s vision for a peaceful residential community remains largely intact.

There are no high rises in Pacific Palisades, and when developer Rick Caruso built a 125,000-square-foot shopping mall in the heart of the community, it was conditioned to blend in with the residential character of the surrounding neighborhood.

Members of the Pacific Palisades Historical Society commemorated the centennial by planting an oak sapling at the site where the original founding ceremony took place. On May 7, they hosted the official Centennial Celebration in Temescal Canyon, not far from where huge groups gathered to hear open air sermons in the 1920s, and not far as the crow flies from where Ysidro Reyes built his home in Santa Monica Canyon in 1838, or where the Marquez ancestors still rest in the family’s cemetery, or where the ancestors of the Tongva people lived for thousands of years. This is a community with a deep, long, and fascinating history.

Did you know?

Descendants of the Marquez, Reyes and Sepulveda families still live in the Los Angeles area. The Marquez family maintains their family’s private cemetery on Haverford Avenue; the last half acre of the Rancho Boca de Santa Monica was declared a City of Los Angeles Historic Cultural Monument (Number 685) in 2000.

The site of the Port Los Angeles Long Wharf is California Historical Landmark No. 881, but there isn’t anything to see. There is a sign at Will Rogers State Beach commemorating the Long Wharf, and a few pylons are sometimes visible at low tide, but the mile-long wharf, the Japanese fishing village, the hotels and bath houses, and the train route have completely vanished.

The spot where the Pacific Palisades Association celebrated the first Founder’s Day is preserved in a tiny pocket park on Haverford Avenue.

Reverend Scott never realized his utopia, but his church is still there—a nice example of 1920s religious architecture. The Self Realization Fellowship and Lake Shrine Garden, dedicated to the life and teachings of Paramahansa Yogananda, has become the spiritual heart of the community (yogananda.org), while the Getty Villa Museum (www.getty.edu/visit/villa) is an international center for arts and culture. Villa Aurora, the home of the Feuchtwangers, and the Thomas Mann House, remain important cultural centers that continue to promote the arts and raise awareness about the history of exiles: www.vatmh.org/en/artists-residence.html. These institutions fulfill Scott’s vision in ways he could never have imagined.