The postcard: inexpensive to buy and send, requiring only a sentence or two and a stamp—it’s the perfect combination of economy, brevity, and sentiment. This fragile bit of paper has carried more than just messages from far off places, it remains an effective advertising tool and once played an important role in the development of the West, and how the East viewed places like California.

Postcards originated in the mid nineteenth century as an inexpensive way to send a short message—the Twitter of its time. One would think that sending a small rectangle of cardstock through the mail would be a simple matter, but when the idea was first introduced, it created shockwaves. Postcards were revolutionary.

Writer Monica Cure wrote a concise history of the postcard for the June 22, 2013 Los Angeles Times—“Tweeting by Mail: The Postcard’s Stormy Birth.” She describes Prussian postal official Heinrich von Stephan’s 1865 proposal for an inexpensive postal card made of stiff paper as “radical.”

“Who would forgo their privacy, even for the sake of convenience and frugality?” Cure asks.

the Library of Congress

The answer? Almost everyone. When the Austrian Hungarian Empire issued a postcard four years later, it was an instant success.

“Three million postcards passed through the Austrian post within the first three months,” Cure writes. “Nations around the world quickly issued their own official postcards. Seventy-five million were sent in Britain in 1870, the year it adopted the new medium.”

The first American postcard was approved in 1861. The US Congress passed an act that allowed privately printed cards to be sent in the mail, provided they weighed less than an ounce. John P. Charlton immediately seized the opportunity and copyrighted the first American postcard, but it took a while for the idea to catch on.

In 1870, the same year that Britain introduced the post card, an American entrepreneur with the euphonious name Hymen L. Lipman developed his own version of Charlton’s cards: Lipman’s Postal Cards. They were popular. Two years later, the US government got into the postcard business. Congress passed legislation authorizing the production of government-produced postal cards.

The government produced cards cost one penny to mail. The sender was permitted to write on just one side—the other was reserved for the recipient’s address. These cards were the only ones permitted by law to have the words “Postal Card” printed on them. Privately printed cards were still permitted, but they cost 2 cents to mail, and their publishers were not happy about being shut out. They lobbied for change.

In 1898, Congress finally passed an act standardizing the postal rate for all post cards. Privately printed cards had to have the words “Private Mailing Card, Authorized by Act of Congress of May 19, 1898,” on them, but they now cost the same to send as official government postal cards.

The twentieth century ushered in the golden age of postcards. Historians estimate that a staggering 200 billion postcards were circulated just in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Improvements in photography and color printing revolutionized postcard production, offering dazzling color views of famous landmarks and landscapes.

Swiss inventor Hans Jakob Schmid, who worked for Orell Gessner Füssli—a printing company that had been in business since the 16th century, invented a color printing process called Photocrom in the 1880s. The company patented the invention, and founded Photochrom Zürich. It’s still in business. The revolutionary new color printing process involved adding layers of color to a black and white negative to create a color image that could be mass produced. Postcards were no longer just an inexpensive way to send a message, they had become a form of art. Postcard fanciers started clubs and traded cards with kindred spirits in far-off places. The world got just a little smaller.

The early color photo images were eye-catching, but left little room for writing. In 1907, after much debate, the U.S. Postmaster issued an order that messages would now be permitted on the address side of a postcard (who says the government never gets anything done?). The world, summer vacation, and advertising would never be the same.

Postcards appeared everywhere. Every hotel had its own, so did shops, restaurants, gas stations, and roadside attractions.

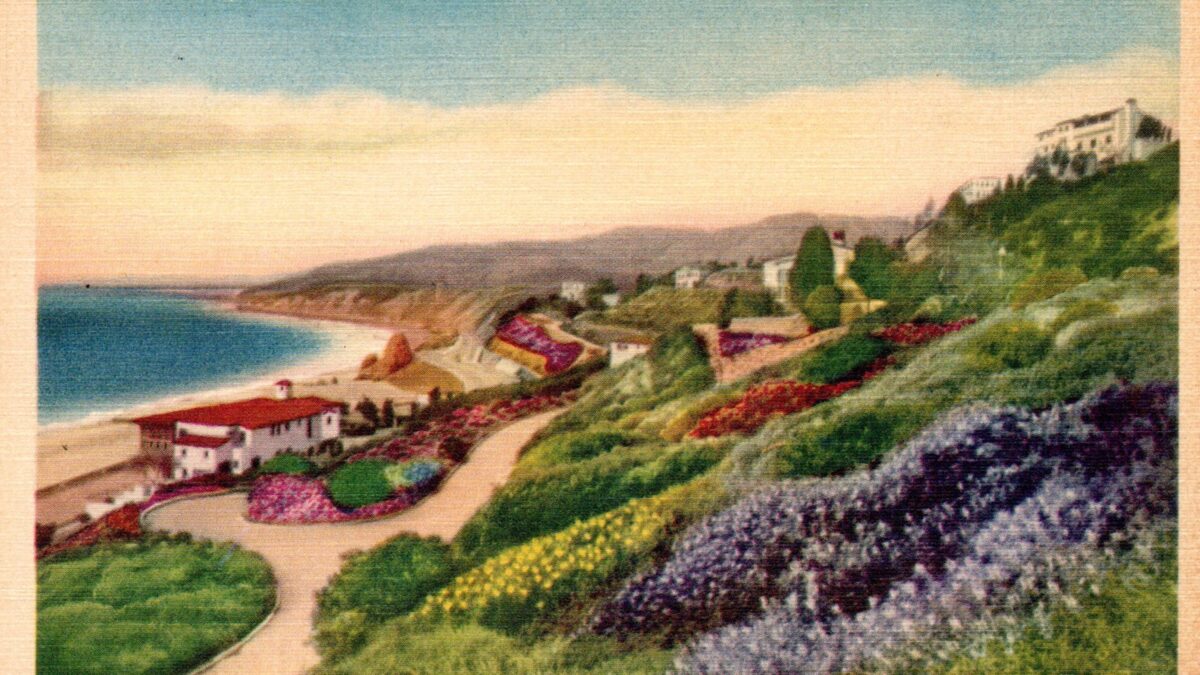

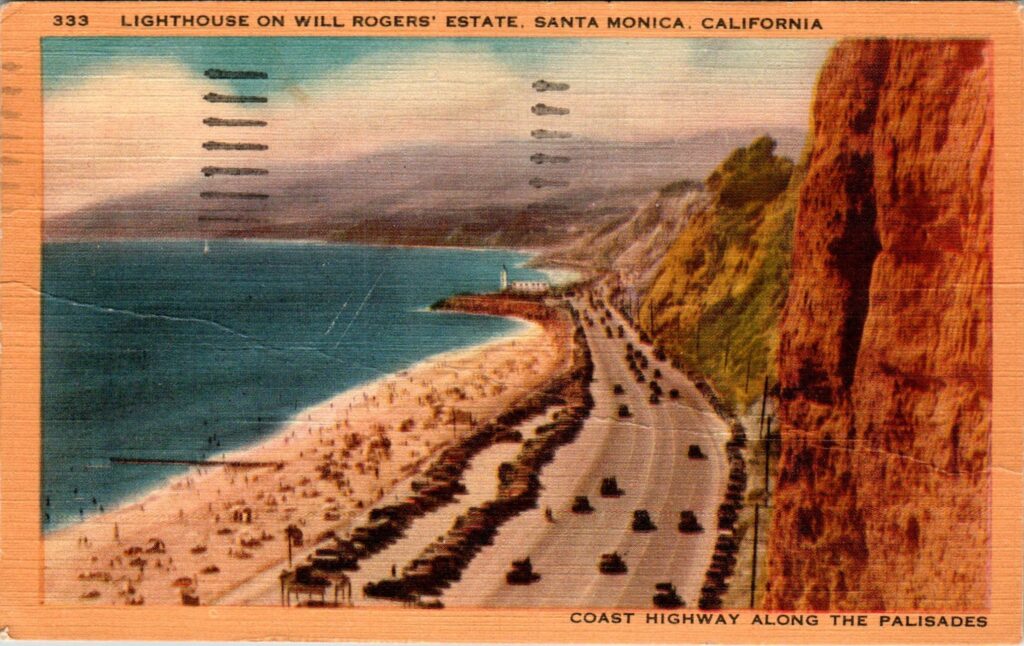

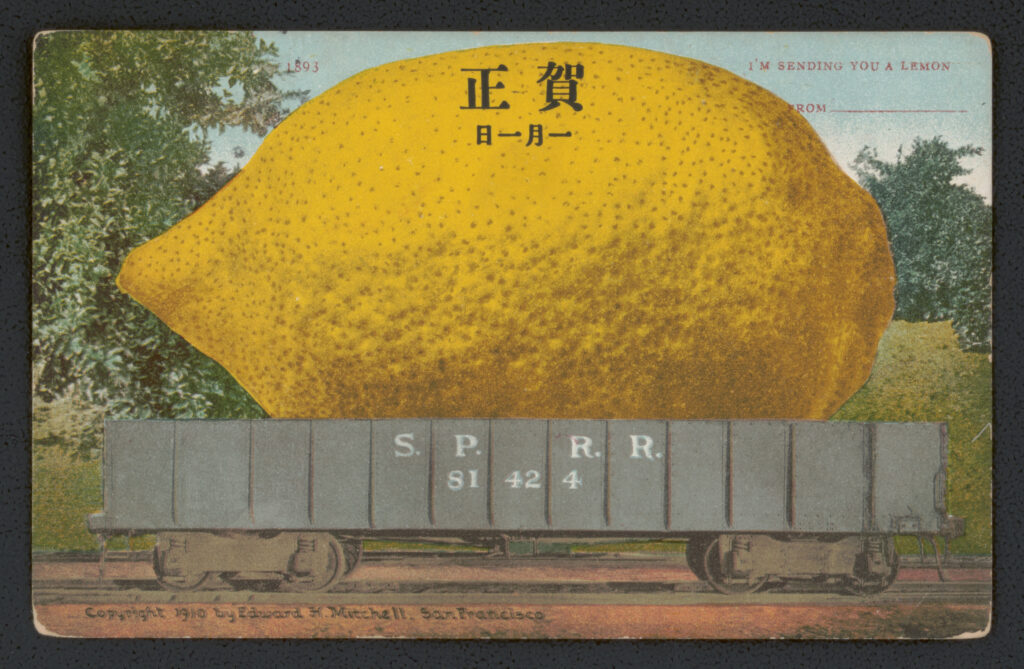

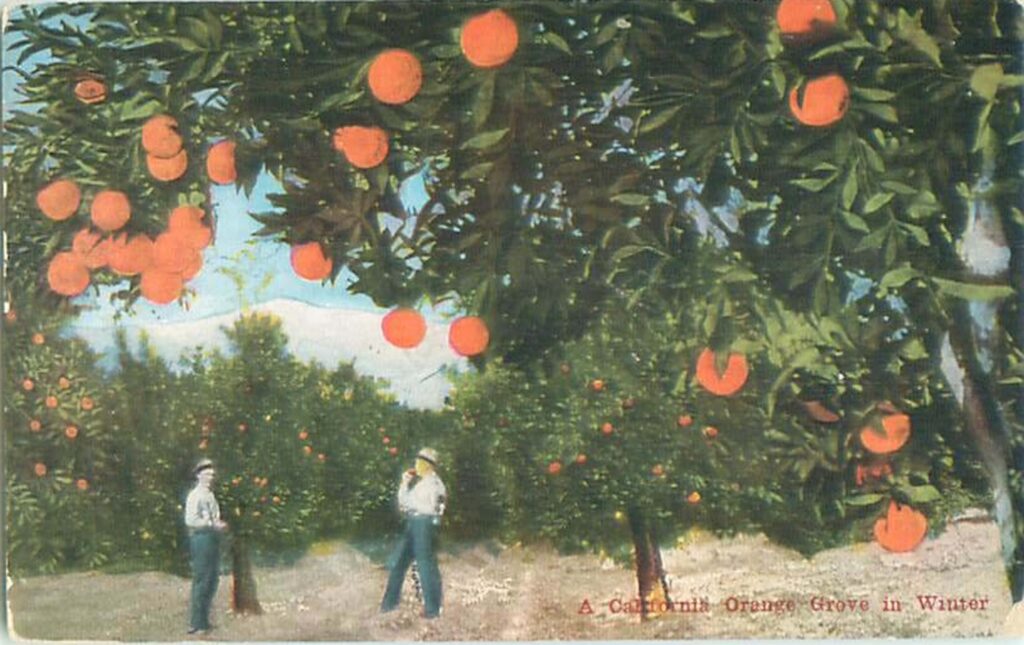

The postcard was also an ideal medium to promote bigger ideas. It became a small but powerful tool in the campaign to market California. Postcard pictures depicted orange groves and blue skies, with snow capped mountains in the background, with captions proclaiming “California Winter,” or “a unique vista seen only in California!”

Local postcards advertised attractions like the Los Angeles Alligator Farm, and romantic and improbably colorful views of new real estate developments like Castellammare, overlooking the Pacific on the coast just east of Topanga. The subject matter may be wildly different, but the goal for both was the same, enticing customers to come see the wonders they advertised in person.

This was the glamorous, carefree California lifestyle distilled down to a photograph and a few words. Seascapes and dramatic mountains, palm trees and sunsets, luxurious seaside resorts and the houses of the “stars” were sure to delight the folks back in snow covered Minnesota, even if the sender only sent their love or a few banalities scrawled on the back: the “weather’s fine,” and “wish you were here.”

Entrepreneurs and artists designed their own postcards. The book Postcards from Mecca. The California Desert Photographs of Susie Keef Smith and Lula Mae Graves 1916-1936 chronicles how Smith, the postmaster for a tiny town on the edge of the Salton Sea, and her cousin Graves, scoured the desert for photographic subjects to sell in the post office spin rack. Armed with a huge box camera and a .38 revolver, this duo created not only postcards, but a vibrant photographic record of life in the desert.

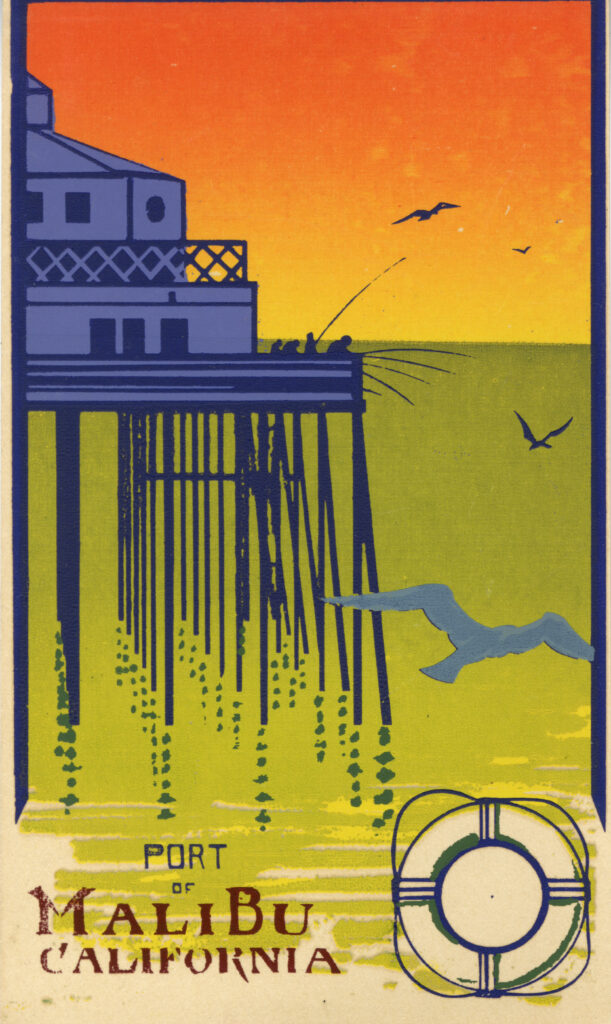

Closer to home, extraordinary artist and printmaker Paul Dubosclard created hand printed serigraph postcards of Topanga, Malibu, Santa Monica and the Santa Monica Mountains.

Paul Dubosclard hand printed a series

of postcards using screen printing or

serigraphy, each one an individual work

of art. This one depicts the Malibu Pier.

Image courtesy of the Topanga Historical

Society, Alli Acker Archive.

John Brewer is in the process of writing a book on Dubosclard. In a recent presentation for the Topanga Historical Society, he described the meticulous detail that went into each image: miniature masterpieces for any passing visitor to buy, each one subtly different, each one requiring many exacting steps to create. Dubosclard’s postcards were produced in the 1940s and ‘50s. They were the antithesis of the mass produced postcards available at every gas station in the west, but they also present a romantic view of California life.

In her 2021 book Postcards: The Rise and Fall of the World’s First Social Network, historian Lydia Pyne reflects on the cultural significance of postcards.

“From the transatlantic women’s suffrage movements, to emerging middle class tourism, to the nascent photojournalism of the 1900s, to the postcards sent and received today, postcards cultivate human connections, linking people across the globe, one picture at a time,” Pyne writes. “Postcards have left an indelible imprint on the history of human communication, unmatched by any other material medium.”

Today, messages that were once scrawled on the back of a postcard are more likely to be sent via text, or posted on social media, but postcards persist as souvenirs from favorite destinations, and as nostalgic reminders of lost landmarks and lost loved ones. It doesn’t matter if it depicts the pyramids of Egypt or just a long vanished motel, there’s a certain magic in the humble postcard: it’s an envoy whose message, written in faded ink, brings news, good wishes, and love from a vanished past.

The weather’s fine. Wish you were here.