During 2022, Florida Governor Ron Desantis has signed into law measures to evaluate which books should and should not be available within individual public school classrooms and libraries. Some of the books facing a great deal of scrutiny clearly target black writers whose history-writing offers a more diversified account of our nation’s past. Restricting these books leads to greater dependence upon state-approved and district-adopted history texts that typically offer a generic and disingenuous recitation of people, places, dates, and events.*

Under a banner of “parental rights,” this Florida legislation—being adopted in a number of other states, as well—is having a chilling effect among teachers who now must second-guess the decisions they make and the resources they choose to enhance their instruction.

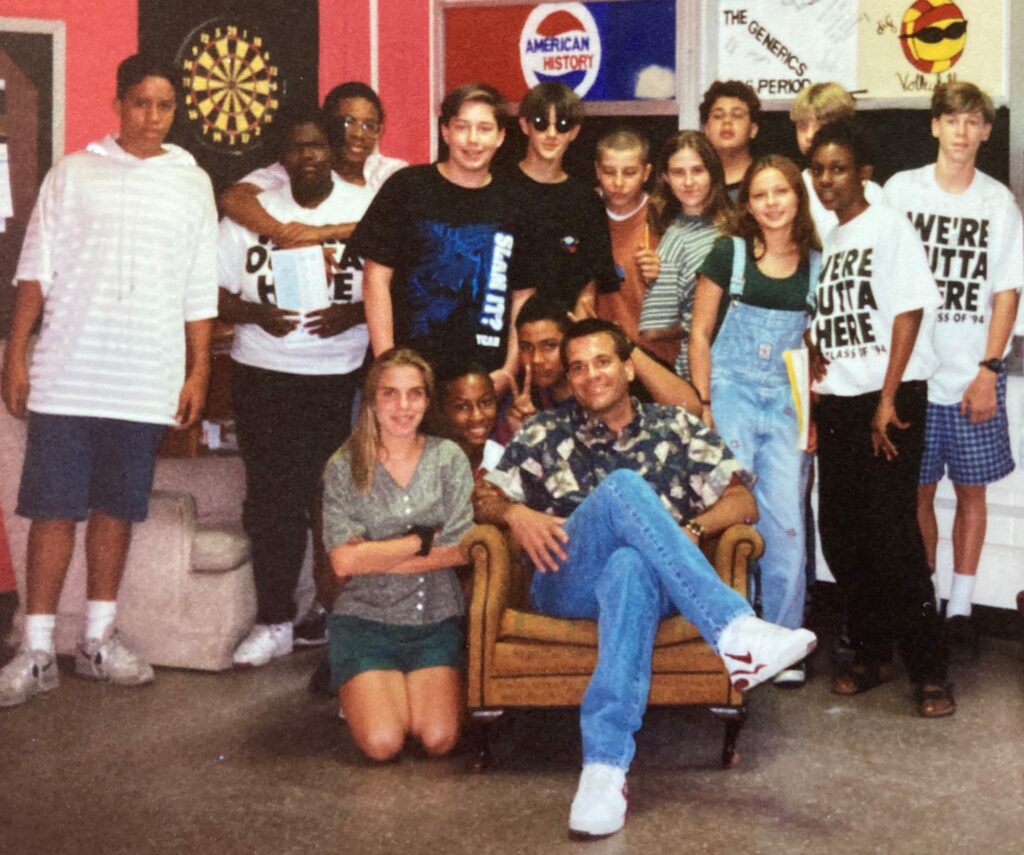

I spent the final decade of the twentieth century teaching eighth grade American History in a Florida public school. From a distance, I have watched with dismay as conservative lawmakers handcuff educators in their efforts to develop critical thinking skills and a spirit of toleration among their students.

This development should come as no surprise as the country continues to be starkly divided over emotionally charged socio-cultural issues. As so often is true, books have the potential to define the parameters of this debate that is quickly beginning to resemble a battlefield.

The most significant casualties in this ongoing cultural war are students and teachers prohibited from engaging with controversial ideas in an environment now peppered with illusory threats of retribution and punishment.

Even before the current round of state-mandated censorship, I taught a lesson during my Floridayz whose purpose was to challenge the very type of government overreach that we are now witnessing. I can only hope that these former students, who are now likely Florida voters, are recognizing what is happening in their state.

I offer a personal teaching moment to illustrate my point.

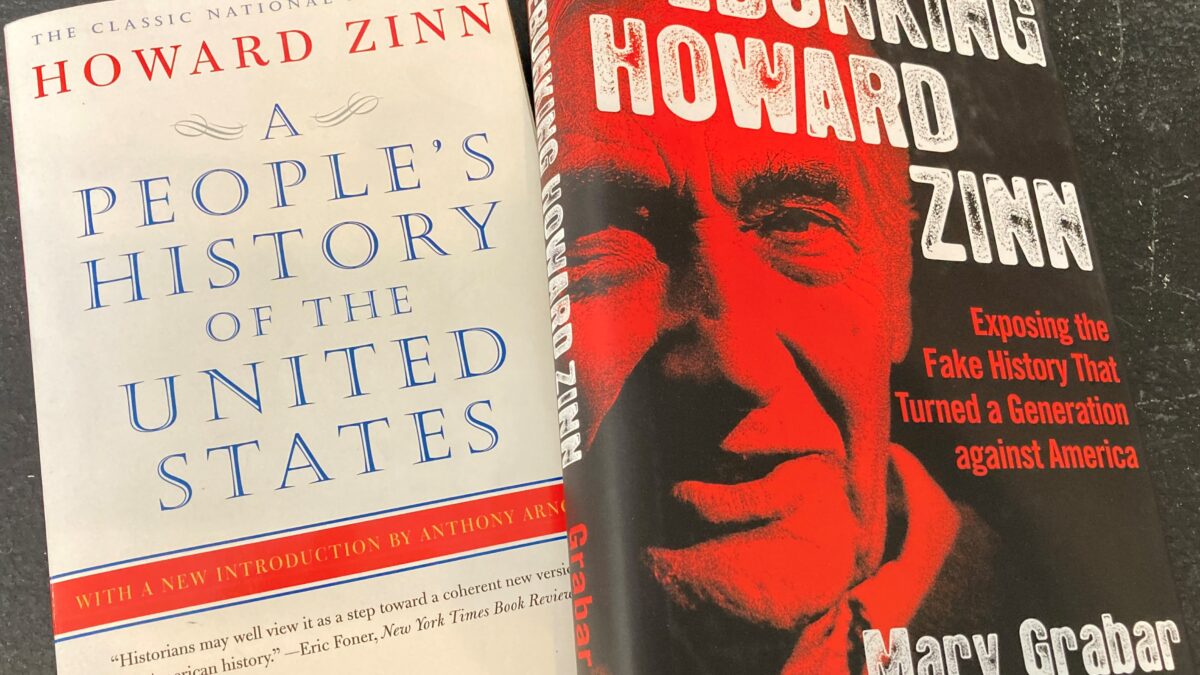

One of the most important books in my American History classroom library was A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn.

As we worked our way through the state curriculum, supplemented by the state-approved American History text, I would occasionally offer Howard Zinn’s take on things as an exercise of “comparing and contrasting” in order to engage students in learning how to go about “evaluating different sources of information” as the state standards dictated.

One of my favorite exercises involved comparing the challenges faced by the Jamestown, Virginia colonists of 1609-1610 as portrayed in the state-approved American History textbook with observations from Howard Zinn’s assessment of the same events. A typical eighth grade American History text reads like this:

Jamestown Survives

The colonists faced hardships of disease and hunger. The colony survived its first two years because of 27-year-old Captain John Smith, an experienced explorer. Smith forced the settlers to work, explored the area, and sought corn from local Native Americans led by Chief Powhatan. When John Smith returned to England, Jamestown lacked a strong leader. The winter of 1609-1610 became known as the “starving time.” Fighting also broke out with the Native Americans.

Howard Zinn described these same events by citing a primary source – the gold standard of good history—the Journals of the Virginia House of Burgesses dated 1619. During the “starving time” the Jamestown colonists…

…driven thru insufferable hunger to eat those things which nature most abhorred, the flesh and excrements of man as well of our own nation as of an Indian, digged by some out of his grave after he had lain buried three days and wholly devoured him… one among them slew his wife as she slept in his bosom, cut her in pieces, salted her and fed upon her till he had clean devoured all parts saving her head…

So, kids, why does your state-approved history textbook read that “colonists faced hardships of hunger and disease” while Howard Zinn tries to ruin your lunch? (Discuss with your small group.)

How are the colonists portrayed in the textbook? Are they the same type of people that Howard Zinn describes? So, what kind of people do you think they really were? (Discuss as a class.)

What other things in the history textbook paragraph headed “Jamestown Survives” might be worthy of further investigation? (Discuss as a class.)

So, why does all this matter? (Discuss as a class.)

I summarize the lesson with a bit of a mini-lecture that goes something like this:

I have offered you two sources of information regarding the same subject that, while not exactly contradicting one another, tell the story of Jamestown that might lead you to develop very different assessments of what not only happened at Jamestown, but what we are to make of this story in terms of what matters to us, today.

I am now confident that you will be able to place Jamestown into the larger scheme of things, especially as we learn that the Jamestown colony was only the first of many English settlements that eventually became the United States. However, there is a larger lesson here; one which, if taken to heart, can help make of you a better person, a better citizen… and that lesson is this:

Throughout your life, you are going to be bombarded with information, and much of it is not going to add up. So, here are some things to consider as we engage with a variety of sources of information in our study of American history.

Is the source of information reliable? Do other sources confirm or contradict the source? Does the information itself seem plausible, consistent with what you already know? Do others who you respect and trust value this source? Are there ways to check up on the reliability of this source? Does the source of information have any interest in having you think or behave in a certain way?

Finally, there is a third source of information in this exercise that you may not have yet considered; one that is perhaps the most influential of all. Who decided that we should learn about Jamestown today? Who guided the discussions? Who chose to share Howard Zinn with you? Who chose one Zinn passage over another? Yup, it’s me.

And I am susceptible to all the deficiencies that may exist within any source of information. Even as I do my best to be an objective conduit of our nation’s past, I am a political being, I vote, I care about the issues of the day, I have very strong views about many of these things we will be engaging with. How on earth can you grow to trust that I am an objective person? Well, you cannot… except to the degree that I present myself in an objective manner, struggling the best I can to understand the many nuances of every issue we may come across… even as I hold views of my own that place me personally on one side or the other.

With that said, I do not wish to indoctrinate you into the way I think. I simply hope that you gain the capacity to think… to think for yourself based upon what you see and hear and read; and that you actively engage with a broad universe of information.

If, for instance, you were to investigate Howard Zinn and/or Jamestown, I would welcome whatever alternative sources of information you may discover. Indeed, some have criticized Howard Zinn for portraying American history in a negative light. It is also clear that Howard Zinn is a political liberal who believes that your history instruction has been shaped by those wishing to promote a version of history that celebrates our country without critiquing it.

Howard Zinn is like a lightning rod – one who generates enthusiastic reactions from supporters and detractors alike. In other words, Howard Zinn makes people think enough to react. During today’s lesson, I tried to do the same.

Some may suggest that I have no business introducing you to a version of events outside the American History textbook that has been approved by the state of Florida and adopted by the school district. With that said, I encourage you to share this lesson with your parents tonight and see what they think. I’ll set aside some time during our next class so that those who care to may share their thoughts.

Inevitably, this lesson would ruffle some feathers; mostly those of a few parents each year who heard of Howard Zinn’s take on Jamestown around the dinner table that night— this type of discussion is always more impactful during meal time—and Mr. Morgan’s encouragement to consider and evaluate different sources of information.

The parents who spoke up discovered that there are more productive ways to exercise parental rights than banning books. Indeed, when they saw what I was up to, they all came to understand that engaging fully with our history can enrich the spirit in a way that no eighth grade history textbook can. This became especially true when, as the year proceeded, they began to see me as a relatively reliable source of information. In other words, they learned to trust me.

Perhaps the most important result of the Jamestown lesson is that the students began to notice the language used in our history textbook; particularly the euphemisms deployed to gloss over some of the nasty business that marks our history. There is plenty to celebrate, for sure, but only if we examine the whole story, warts and all.

This is why book restrictions emanating from the state of Florida in 2022 is a tragic mistake; unless, of course, officials in charge there hope to undo more than two full generations of civil rights progress and return our society to an era when children knew their place, spoke only when spoken to, snapped to attention to pledge allegiance to the flag, and did not concern themselves with the full measure of American history (fade to that dopey red hat).

I think now how my Jamestown lesson might go over in a 2022 Florida classroom…. I wouldn’t last five minutes.

*This legislation also singles out books about gender identity often written by LGBTQ writers. I am not yet familiar with many of the books being targeted but hope to address them in the future. For the purposes of this column, I am focusing upon efforts to limit the instruction of the unsavory aspects of our nation’s past; epitomized largely through the study of African American history and the legacies of slavery.