Unstable. Two months into the extended closure of Topanga Canyon Blvd., that’s the official diagnosis for the slide. And on March 28, before the most recent wave of rainstorms, there were reports of increased movement. The Caltrans geologist reported that the situation was “worsening beyond initial expectations,” and added that he cannot predict when the movement will cease. “It is still too dangerous for workers to clear the roadway because of the unstable hillside.”

The slide may not look that bad from street level, but drone footage has revealed an ominous tension crack above the road that indicates that the entire mountainside is moving, and there is no way to safely remedy the situation while the soils are saturated. It’s like trying to contain hundreds of tons of partially set pudding.

Caltrans officials are asking residents to stay behind the safety barriers, no matter how tempting it may be to get a closer look. More rocks could fall at any time.

Caltrans is trying to address safety issues related to the closure, including stationing flaggers at the bottom of one-way Tuna Canyon Road to help guide motorists turning left onto Pacific Coast Highway and to prevent wrong-way drivers from trying to go up the road.

Residents are being assured that the county Department of Public Works is monitoring county maintained roads throughout Topanga, including Tuna Canyon, to make sure they remain free of hazards.

The closure has resulted in traffic jams in some unlikely parts of the canyon. Residents have little choice other than coping as best as they can. Commuting will remain a challenge until the road is safe to reopen, and that probably won’t be soon.

The Topanga Town Council’s One Topanga webpage offers some of the best information on the closure: onetopanga.com. The other critically important resource is TCEP.org.

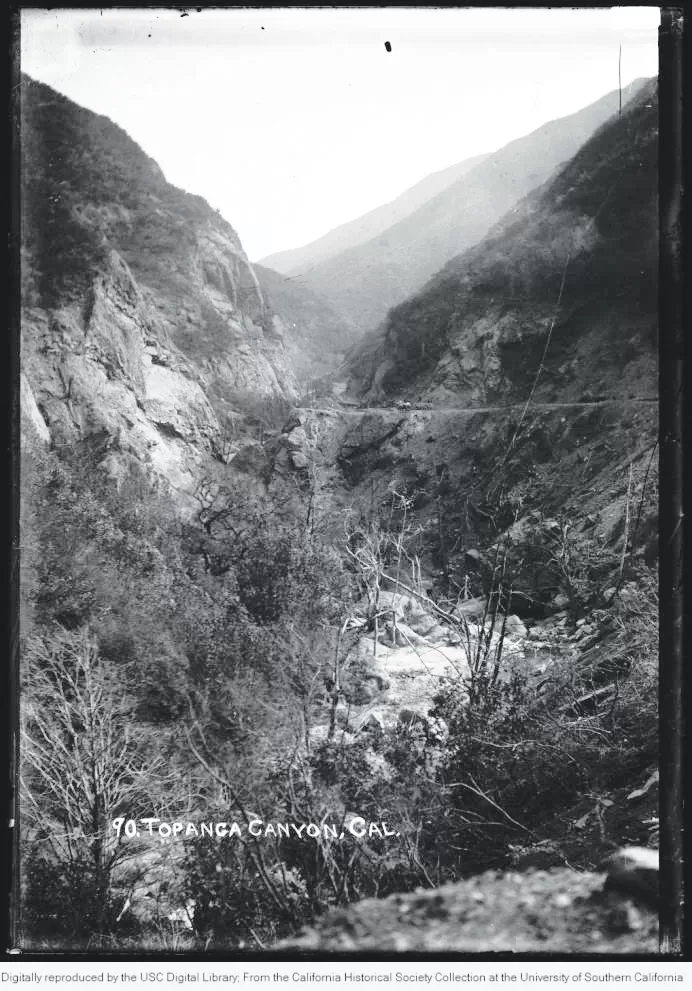

Topangans are used to road closures, but there is still no end in sight for this one. A big part of the problem is the road itself. It was built through geologically unstable and almost impossibly steep terrain without the benefit of modern engineering in the early years of the twentieth century. Keeping rocks and mud off the road has been a constant battle.

The first Topanga storm-related disaster to make headlines was the winter of 1914, when the dirt road leading to Topanga from “The Malibu Road” was washed out during heavy rains. Nearly a year later, the Los Angeles Times reported that “road work was being rushed by county construction gangs,” but that, “At present the only visitor to the region is the mailman, who rides a horse.”

In 1934, boulders rained down on Topanga Canyon Boulevard and cars were buried in mud. It happened again in 1938, the legendary flood year that resulted in the channelization of many of Los Angeles’ waterways.

In January 1952, Topanga Creek overflowed during heavy rains, flooding houses with more than three feet of water and washing out a 100-foot-stretch of the road.

Flooding in Lower Topanga Canyon happened so frequently that in 1960 the county abandoned the old Topanga Canyon Boulevard intersection, located about 150 feet west of the current intersection on PCH. Years of flooding by the creek had nearly obliterated the old road. It may have been a timely decision because the 1960s brought the area some of the worst flooding on record.

Topanga’s history bible, The Topanga Story, recounts how during the winter of 1962, Red Rock Creek overflowed, turning the road into a river, ripping up oak trees and leaving devastation behind. Mud swamped part of the old school, filling one building “to the doorknobs.” Many families were trapped in their homes, unable to cross the creek.

In 1965, heavy rains reactivated old landslide areas, covering the lower canyon road in debris and shutting down PCH again.

The flooding in the early 1960s was so costly that in 1966, County Engineer John Lambie proposed a county ordinance prohibiting property owners in the Santa Monica Mountains from removing brush on land with a slope greater than eight percent. Various flood control projects were proposed, a few were even implemented, but none of them helped prevent the catastrophic flooding that occurred in January 1969.

A Los Angeles Times article described Topanga Canyon residents, emerging on foot from the canyon after the deluge, as “refugees from a battle. Along the Topanga Canyon floor, cars, like boulders, lay half buried in mud,” the Times reported. The canyon road washed out in three places. Between the washouts were “mudslides hundreds of feet wide,” according to the article.

Topanga Creek swelled to a river 100 yards wide in places. The Times reported that at least ten vehicles on PCH near the mouth of Topanga Creek were swept away when the flash flood reached the coast, including a “small bus” that was carried out to sea.

Coast Guard helicopters were sent in to look for survivors. As many as 500 residents were trapped in the canyon for days.

The rains devastated communities throughout the state, resulting in a California-wide state of emergency. In the Los Angeles area alone 100 people died. Four of the victims were Topanga residents: 32-year-old Gale Gordon and her two children, Mathew, 3, and Heather, 6, died when the hillside behind their home swept the house into the creek. A 34-year-old Old Topanga Road man was killed when his house was buried in a mudslide.

The nightmare was repeated in 1980, when flash floods tore through the canyon, carrying away houses, cars, trees, boulders, a school bus, and two large sections of the canyon road. Residents were left without water or power, and with no viable way out of the canyon, but at least this time there were no known casualties.

The Topanga Messenger described the rains as arriving with “terrifying suddenness.” It took months for the road to be repaired. 1980 has gone down in the records as “The Great Flood Year.” It left PCH closed at Big Rock for months, forcing coast residents to take a temporary ferry from Malibu to Santa Monica, or to detour all the way around the mountains. Many parts of California declared a state of emergency.

In 1993, the canyon was once again transformed into a river. Floods generated by heavy rains turned hillsides stripped of vegetation in the 1992 Old Topanga Fire into mud flows. One man died trying to cross the creek. Many were left without power or a way to safely evacuate.

Topanga Canyon Blvd. was closed for 18 days during the winter of 1995, after flooding severely damaged five stretches of the highway between Grandview and Pacific Coast Highway.

On January 9, 2005 a two-storey, 300-ton boulder fell on Topanga Canyon Blvd., completely closing the road for a week. Two-way traffic wasn’t fully restored until early February. “Topanga Rocks” t-shirts were in vogue in the canyon after that incident, produced as a fundraiser for the Topanga Coalition for Emergency Preparedness. Topanga residents usually manage to maintain a sense of humor, even during disasters.

The winter of 2024 is already one for the record books. Parts of Topanga have received more than three and a half feet of rain so far this season. Mopping up is going to take time and a lot of patience, especially since more slides are possible, and not just at the site of the current closure.

There have been other mudslide and rock related closures. Many of them. Some last a few hours, others a few days, some, like this one, drag on for weeks or even months. Almost everyone who lives in the area has a story about them. Topanga’s beauty is tied to the rugged and dramatic mountains that surround and enfold the community. Winters like this one remind us that the mountains aren’t just scenery: they are a living, changing, dynamic force, one that shapes the lives of everyone who calls this place home.

Thank you Suzanne, for this thorough and measured history of previous TCB road closures! It really gives a moderated perspective on the current situation – we all get so wrapped up in our personal prisms and forget that we’re just a small part of the beautiful but every changing terrain we’ve all chosen to live in. Excellent reminder… this will pass!

I was raised in the small community of old Topanga. Right behind the old community store.