Many businesses have been turned upside down by the digital revolution, but of those that have survived, few have changed as radically as the newspaper industry.

When the Los Angeles Times Building opened in all of its art deco glory in 1935, Times Mirror Company president Harry Chandler declared it, “A monument to the progress of our city and Southern California.”

The building was designed by architect Gordon B. Kaufman to be a kind of secular temple to the newspaper industry. In the lobby stood a massive aluminum globe surrounded by bronze panels depicting industry, religion, science, and art, and ten-foot-high murals by Hugo Ballin (the artist who painted the rotunda at the Griffith Observatory) celebrating the history of journalism and Southern California.

The journalists who worked there had expense accounts, stenographers to transcribe new stories transmitted by telegraph or phone, a newsroom that employed hundreds and was a beehive of activity, and a smorgasbord of news to fill the pages.

Sometimes the paper itself was the source of the front page story. The spectacular new building replaced a previous office that was blown up in 1910 by pro-union activist brothers John and James McNamara—the blast killed 21 people and destroyed the paper’s printing press.

The L.A. Times began publishing in 1881. By the start of the 20th century, it was already the biggest paper in Los Angeles, but it had plenty of competition. The Los Angeles Daily News debuted in 1869, the Los Angeles Tribune in 1886, and the Los Angeles Examiner in 1903.

Unfortunately for residents of the Santa Monica Mountains, local issues were only covered when they were of general interest: a fundraising drive by the Citizens of the Upper San Fernando Valley to grade the wagon road through the Topanga Pass earned a paragraph in The Times in 1895—they raised $700. The opening of the coast route—Roosevelt Highway—through Malibu in 1927 merited a two-page spread. L.A. Times artist Bruce Russell outdid himself for the occasion, augmenting photos of steam shovels and the first cars to travel the road with an illustration of Father Junipero Serra admiring the view with a Native American in a feathered headdress straight out of central casting.

The Los Angeles Star—La Estrella de Los Angeles—founded in 1851, was L.A.’s first weekly newspaper and it contains the earliest mention of Topanga in the news. On May 1, 1858, the paper reported that Leon Victor Prudhomme had filed a land claim for Rancho Topanga Malibu Sequit. Nearly two decades later, on August 3, 1875, the Los Angeles Herald reported that the claim had finally been settled.

Sometimes reports of local news came from farther afield. On August 20, 1885, the Daily Alta Californian mentioned “A big fire in the Topango Canon. The article states that the smoke attracted much attention, “darkening the whole country.”

When the steamer St. Croix burned and sank off of Malibu, The Delware Pilot described it as “a holocaust at sea,” while the San Francisco Call provided the first report that the crew and passengers had miraculously survived. In those days, reporters headed to the nearest telegraph office to transmit the news to their editors, and competition to break a story was fierce.

That didn’t mean that the news reached the people it was about in a timely manner. Until roads and postal service arrived in the mountains, the news was already old by the time a newspaper of any type made its way to homesteaders.

The Los Angeles Herald reported in 1907 that “Topango canyon settlers,” weary of having to send a rider to town for their mail once a week or once a month, “had petitioned the post office authorities to establish a delivery station in the mountains.”

Homesteaders in the western Santa Monica Mountains had to wait for the coast route to open in the 1920s before they had access to mail—and newspaper—delivery.

There weren’t any truly local news sources until the Santa Monica Evening Outlook launched in 1918. The paper became the Evening Outlook in 1929, and remained in publication through 1986, reporting on the Westside, Topanga, Malibu, and much of the Santa Monica Mountains.

The Outlook was joined by the Palisadian-Post in 1929, but that paper’s early focus was on the development of the Palisades and not the concerns of the community’s mountain neighbors. The lead story in the first issue was about a $1 million plan to pave Marquez Avenue/Chautauqua.

In May of 1942, Malibu resident Charles Lapworth published the first edition of the Malibu Bugle, the Santa Monica Mountains first weekly newspaper. The paper was created to spread news to the World War II Civil Defense volunteers in the Malibu Sector, which comprised 300 square miles, including Calabasas, Topanga and Malibu.

A copy of the second issue is held by the Los Angeles County Library. It’s a photocopy of a photocopy and it appears to be the only surviving issue of this short-lived publication, but it provides a fascinating glimpse of life in the area during WWII.

One article in The Bugle details a farewell gala for soldiers quartered by “Mrs. Altomari and Mrs. Lola Adams Gentry, fondly known to every man in uniform as ‘Aunt Lola,’” at the “Ramirez Canyon Outpost.” There’s also an account of weapons practice off shore at the Malibu Colony.

“The good ship Prentice did her patriotic bit,” the paper recounts. “For weeks she lay just off Malibu Beach, her active sailing days ended, and took everything the flying circuses of P-38’s could pour into her.”

Despite the focus on the war effort, the paper also chronicles ordinary events, like the birth of a foal named “Topanga,” born at “Frank Lloyd’s ranch.”

Topanga Canyon resident Hugh Harlan and Malibu residents Reeves and Reta Templeman were the next to try their luck with local papers. Harlan published the Topanga Journal and the Malibu Monitor from 1946-1952. The Templemans had a longer run with the Malibu Times. In 1987, they sold the paper to its current owner, Arnold York. It’s still in print, although the office building that has housed the paper from the beginning is currently for sale.

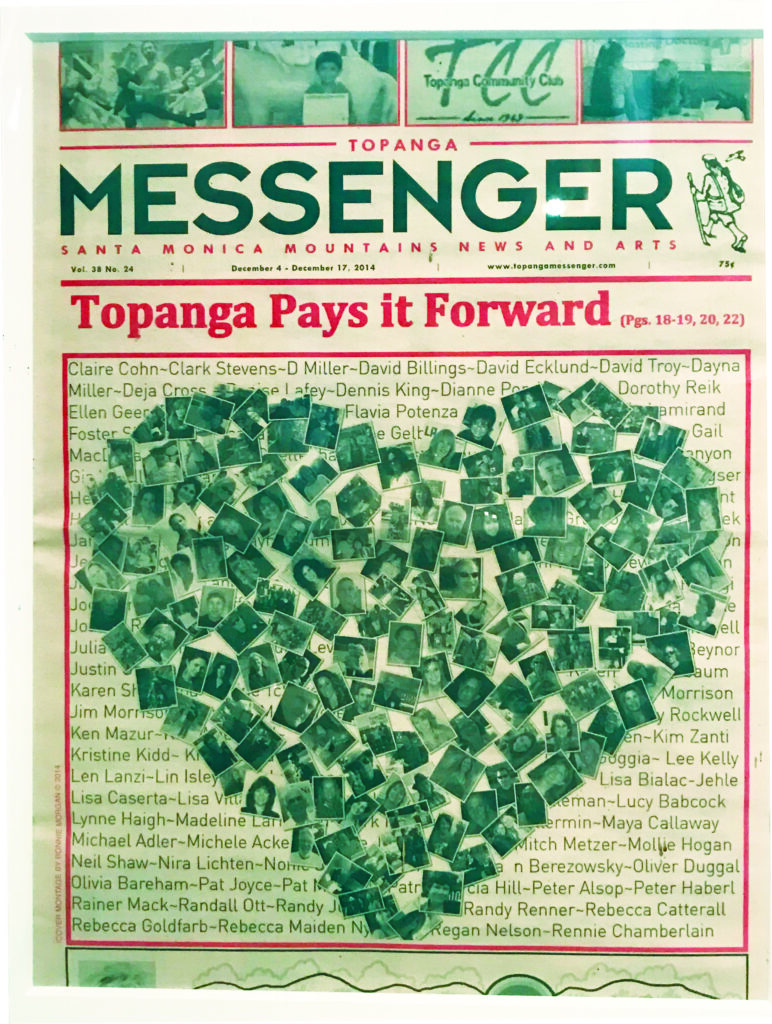

In 1976, two new local weeklies debuted: the Malibu Surfside News, published by Anne Soble, and the Topanga Messenger, with publisher Ian Brodie at the helm. The Acorn arrived on the scene in 1998, a family of newspapers serving the communities in the northern side of the Santa Monica Mountains, with editions in Calabasas and Agoura Hills, Moorpark, Camarillo and the Simi Valley.

Journalism has faced numerous seismic shifts in recent years and many papers, including small local weeklies but also giant dailies, have folded. The presses were replaced by photo-typesetting machines in the 1970s and then, in a second major transition, to computers in the 1990s. Staff writers have been replaced by freelancers, and the newsrooms of the earlier era are the stuff of noir films, not real life, but the industry continues to survive.

The L.A. Times is still the biggest newspaper in the Western U.S., surviving buyouts, staff reductions, bankruptcy and other issues in recent decades. The current owner of the L.A. Times, Patrick Soon-Shiong, opted to move the headquarters to El Segundo, rather than continue to rent back the paper’s historic space from the new owners, who plan to build a pair of luxury apartment towers at the site.

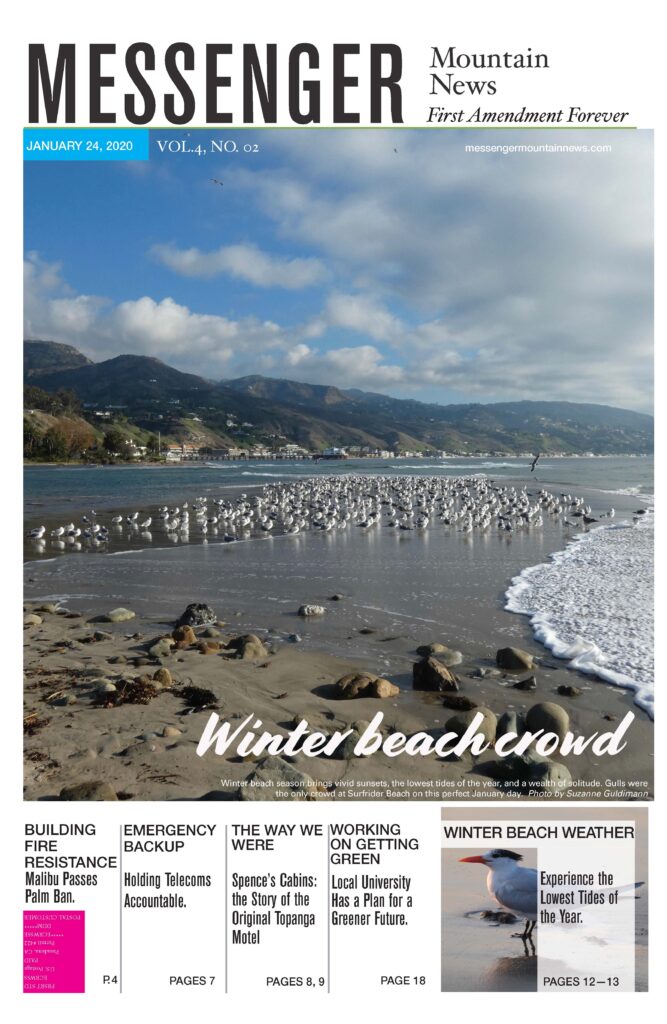

The Malibu Surfside News was sold in 2013 and stopped publishing its print edition during the Coronavirus pandemic. The Topanga Messenger concluded a 40-year run in 2016. It’s successor, the Messenger Mountain News, bridged the gap for three years, and journalism remains alive and well in Topanga, which is currently home to two biweekly publications.

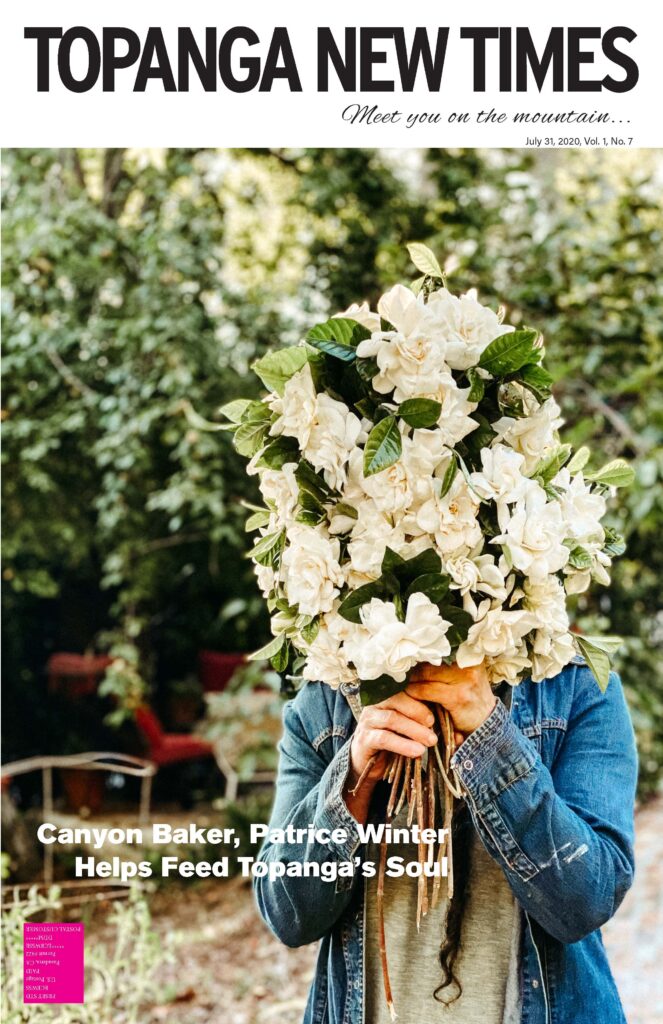

The Topanga New Times got its start in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic. Like journalists everywhere, we’ve learned to work from home without an office, conduct meetings and interviews via Zoom, and find stories to share with our readers in a time when most activities are on hold. We are also spreading out into videos, podcasts and other mediums. The tools have changed, but despite those changes, there are still stories to tell.

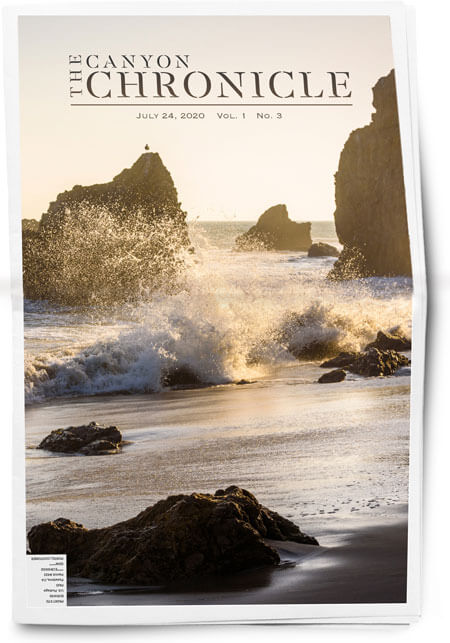

acquainted with the occupation knows only too well. The fact that Topanga has

been graced with several is an interesting commentary on this community. From

left to right: Topanga Messenger, Messenger Mountain News, The Canyon Chronicle and Topanga New

Times.