And how many people were with you? That’s what the 2020 U. S. Census wants to know. The audacious project, to count everybody in the country every ten years, is required by the Constitution. Not a sample, poll or survey, but the task requires an actual head count of all persons of every age alive in the United States on Census Day, which was April 1 (no fooling!)

The resulting data apportions seats in the House of Representatives and votes in the Electoral College, justifies the distribution of an estimated $1.5 trillion in federal funds, and measures the country’s shifting demographics.

By mid-March, nearly every U. S. household received an invitation (in twelve languages) to respond to the Census online, by phone or by mail. Households in areas with a high senior population or low internet connectivity or subscription rates, received a paper questionnaire to mail back to the Census Bureau.

By April 8, 46% of the invited households had provided information. Those that didn’t were then sent a paper questionnaire.

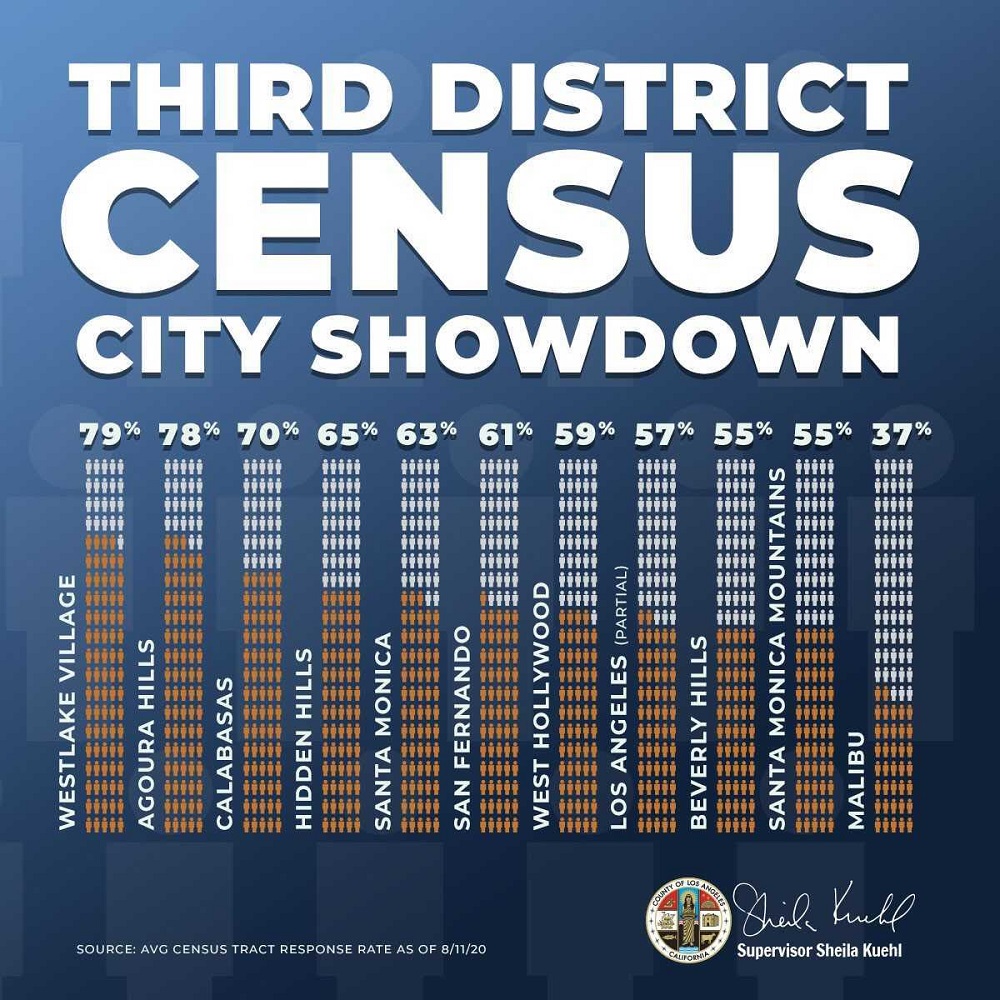

According to Congressman Ted Lieu, as of August 6th, the Census self-response rate in California’s 33rd District (wherein lies Topanga Canyon, the Santa Monica Mountains, and much of western Los Angeles County) was 58.9%. By August 18, California’s overall response rate was 65.5%, slightly surpassing the 63.8% national response rate.

So far the process seems relatively cheap and easy. But only counting the respondents who are convenient to count, does not paint a true portrait of the face of America. What about the four-out-of-ten households that didn’t yet respond? Their info must be chased down by in-person interviewers known as Enumerators, who will return as many as six times to the same residence to capture the necessary data.

Hired from within the community, Enumerators are at this moment investigating Topanga’s main drag, twisty back roads, gated driveways, yurts, guest homes, mansions, trailers, converted garages, rentals and single family residences to verify addresses and find eligible respondents (who are at least fifteen years of age, and knowledgeable about the property’s occupation on April 1.)

Masked and carrying official U. S. Census Bureau ID badges, government-issued smart phones and canvas attachés, Enumerators knock on doors, and retreat six feet for public health. If lucky enough to find somebody at home, the Enumerator receives a range of greetings, from enthusiasm for the cause, to frustration at yet another visit when the respondent already told three Enumerators this week that the questionnaire is in the mail, to threats of bodily harm.

When faced with a hard refusal, an Enumerator is trained to thank the resident, note the failed attempt, and be on her way. The task cannot be completed without the voluntary cooperation of the American public. Though Census law may levy a $100 fine for not answering, and a $500 fine for fraudulent answers (jail time was removed from the Census code in 1976), penalties are generally not enforced. But technically, if Enumerators record six fruitless attempts at a verified address, the information could form the basis for prosecution.

Folks balk at volunteering personal household information (names, ages, dates of birth, race and ancestry) to government agencies out of concerns for privacy and confidentiality, and good old-fashioned fear and orneriness. Many are not won over by the Enumerator’s sworn oath to confidentiality, nor impressed by the Title 13 criminal penalties of $250,000 and five years in prison to any Enumerator caught divulging Personally Identifying Information. Many respondents refuse to answer more than the basic population questions.

Immigrants may be especially fearful, even though the U. S. Census Bureau promises not to share data with other agencies such as ICE, IRS, DHS or the FBI. There was that incident when 1940 census data was secretly used in one of the worst violations of constitutional rights in US history, leading to the internment of 120,000 Japanese-Americans. And after 9/11 the Census Bureau provided population statistics to the Department of Homeland Security, including detailed information about how many people with Arab backgrounds lived in certain zip codes.

Even the most secure data practices are susceptible to hacking or insider leaks. And in the hands of a crafty statistician, good data may be framed with a stereotyping or stigmatizing slant, potentially harming a target group.

So, there are plenty of reasons people may be wary of participating in the Census, which could lead to an undercount of the hardest to reach communities; paradoxically, the very folk who might benefit most from funded programs. At the heart of it, is concern that an undercount could disproportionately help either Republicans or Democrats, and their respective plans for federal monies.

In addition to the usual obstacles, the 2020 Census is beset by the Coronavirus pandemic, which caused abrupt living changes for some people dealing with lockdown; and required immediate public health measures so door-to-door canvassers did not become virus-vectors.

A far bigger threat to the impartiality of the 2020 Census, the Trump Administration,

1) Campaigned to include a question about citizenship. Considered intimidating and potentially contributing to an undercount of Latinos, the plan was struck down by the Supreme Court.

2) Cut the Enumeration period short by one month, terminating the effort after September. Experts predict rushing to deliver the population counts, could produce severe inaccuracies, especially among people of color, immigrants, rural residents and other historically undercounted groups.

3) Appointed three political deputy directors to the U. S. Census Bureau in less than two months. Professional statistical associations view the extraordinary appointments as a partisan attempt to interfere with the Census.

The decennial Census is a bold, ambitious project, mired with as many flaws as humans who work on it. But credible Census results can be a foundation for equitable distribution of resources, and worth shooting for. If you haven’t been counted yet, you can call 1-844-330-2020 (1-844-467-2020 for hearing impaired) toll-free, or go to my2020census.gov.