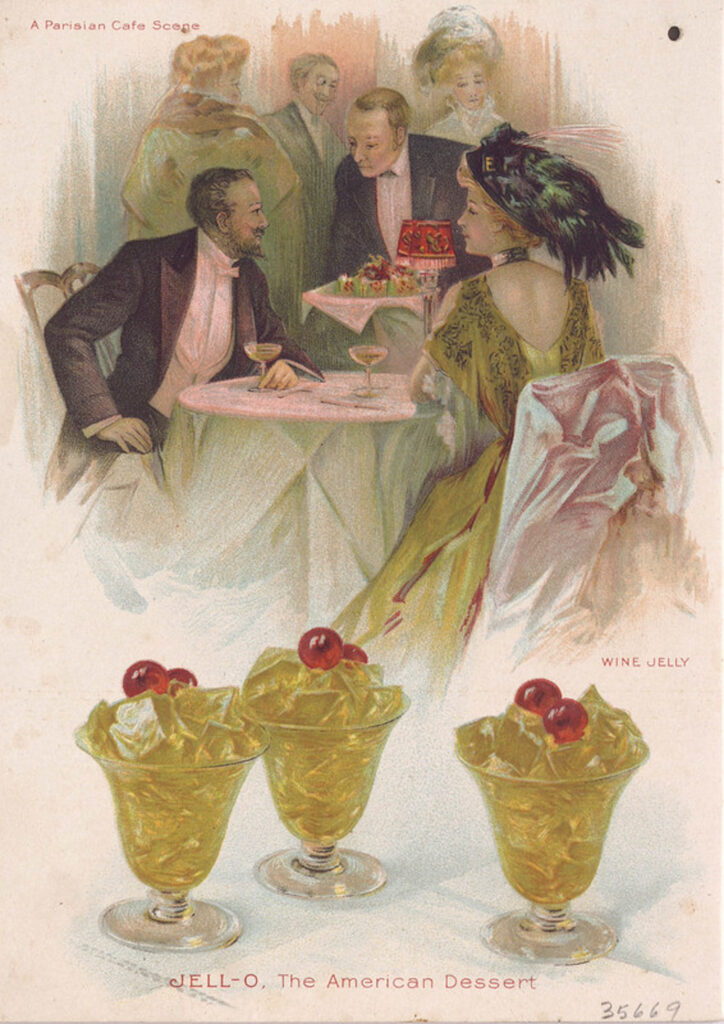

The Jell-O mold, staple of holiday dinner tables and potlucks for much of the 20th century, has a surprisingly antique and noble history. Aspic was a status symbol in European cookery, enjoying its first major vogue in England during the Tudor era, and it has remained a cornerstone of French haute cuisine for centuries. Making gelatin was costly and time consuming. It involved boiling animal parts like bones, skins and hooves for hours to obtain collagen protein. Only the wealthy could afford the animal products gelatin was made from, the labor to create the product, and the ice needed to set the jelly.

Jellied meat pies, and elaborate molds filled with quail eggs, wild game and luxuries like olives graced the tables of the rich and prosperous. Gelatinous consomme made from boiled bones and other various cow and pig bits was bestowed by the wealthy on invalids, the elderly and the less fortunate, and was thought to have curative properties (the bone broth craze is definitely not new).

By the 19th century, the new middle class could afford ice boxes and the industrial revolution was producing factory food products for the first time, including gelatin. Bones, hooves and skins were boiled down in vast cauldrons in factories, leaving home cooks with the simple task of dissolving the end product in boiling water and mixing it into anything the imagination could dream up.

A U.S. patent for powdered gelatin was issued in 1845 to inventor Peter Cooper, who also designed and built the first American steam locomotive, the Tom Thumb, in 1829.

The Jell-O brand name is synonymous today for all kinds of gelatin. It was trademarked in 1885, in Le Roy, New York, by Pearle Bixby Wait and his wife Mary, who added sugar, color and fruit flavor to granulated gelatin to create a packaged dessert mix. The original flavors were strawberry, raspberry, orange, and lemon. In 1899, the Waits sold Jell-O to the Genesee Pure Food Company. The company’s owner, Orator Francis Woodward, seems to have been attracted to Jell-O because the name was so similar to his own product, “Grain-O,” a grain-based coffee substitute described as “a health drink.” Woodward didn’t know it when he paid the Waits $450 for their invention, but that purchase would be the foundation for a mighty, gelatinous empire.

Advertisements in popular magazines promoted Jello-O as an easy-to-make dessert. Clever marketing involved an army of door-to-door salesmen, who gave away samples and recipe booklets. Jell-O’s mascot was an adorable child, a sign that this product was pure and wholesome. It was soon more than just a family dessert. By the 1920s, the iconic Jell-O salad, full of olives and pimentos preserved as if in amber, had taken over the salad course.

Humorist James Lileks, creator of the Gallery of Regrettable Foods (www.lileks.com), has made fun of gelatin salads for decades, but his photo essay on the evolution of Jell-O in the 1920s and 30s is fascinating. Lilek uses Jell-O ads to show how the company weathered the depression and shifted with the times, from depicting Jello recipes as a classy luxury to establishing them as an inexpensive staple during the Depression, something that could be used to stretch leftovers.

“The skill of the early Jell-O booklets is something that deserves our attention and admiration,” Lileks writes. “There’s something quite simple and, well, boring—but the skill devoted to ennobling the humble substance is a triumph of the advertising art.”

Because it contained sugar, flavored Jell-O was rationed during WWII, but it’s popularity exploded in the post war boom time. It was a time of plenty, and gelatin molds reached new heights because of refrigeration. The bigger the refrigerator, the greater the potential to create towering gelatinous castles of jellied shrimp and mayonnaise salad, or canned fruit cocktail and marshmallow. Gleaming new supermarkets filled with canned and frozen foods offered unlimited possibilities, and housewives were egged on by manufacturers, who offered recipes and suggestions that would never otherwise have occurred to anyone.

Although the weirder gelatin salads fill many twenty-first century foodies with a sense of horror, they were practical because anything encased in gelatin will stay fresh, enabling great Aunt Edna to make her infamous avocado and salmon mold the day before she served it, safe in the knowledge that the avocado wouldn’t oxidize or the fish become fishy.

Making a simple Jell-O dessert or salad took only minutes to mix up, but many recipes were fantastically elaborate, requiring an understanding of the relative density of the ingredients to ensure that everything didn’t sink to the bottom, and enough time and patience to refrigerate each layer before adding the next. No matter how it tasted, that towering jello salad with its artful design of egg slices was bound to look impressive.

The great era of the jello mold was over by the 1980s. Working women didn’t have time to fuss with fancy molds and tastes were changing. Gelatin salads are no longer a staple on most people’s tables, but love it or loathe it, Jell-O has a lasting place in American culinary history, and an auspicious future, too. Now owned by industry giant Kraft Foods, “America’s Most Famous Dessert,” remains popular, with many flavors and variations. New trends include spectacular flower cakes and treats like coffee jelly, both of which originated in Asia; and Jello shots, a cross between a desert and a cocktail that evolved from a staple of college parties to a darling of the molecular gastronomy movement, with an exotic range of ingredients and fanciful presentations.

Even elaborate molds are experiencing a modest renaissance. There are blogs and Instagram accounts dedicated to recreating or deriding this delicacy. And like the ghosts in a Victorian Christmas story, Jell-O salads still materialize over the holidays, enlivening family dinners and community potlucks with bright colors and improbable ingredients; a towering, jiggling monument to American innovation and mid century optimism that refuses to yield to post modern cynicism. Try it, you may like it. “There’s always room for Jell-O.”

Vegetarians and those who observe a halal or kosher diet can’t eat Jell-O, which contains collagen from pig bones and skins, but there are a number of alternatives, including pre-packaged mixes made with a variety of non-meat gelling agents. TNT’s resident vegans tried our luck making an old-fashioned gelatin salad with kelp-derived, unsweetened, unflavored agar-agar powder. Agar doesn’t have the same wiggly quality that animal-based gelatin does—its texture is more brittle and less forgiving—but with a little practice it’s possible to make a credible jelly mold that would make Aunt Edna proud.

Cranberry Cherry Pear Salad

1 package of frozen cherries

2 cups of cranberry apple juice

Juice of one lemon

Sugar to taste, we used a third of a cup

Two large, firm Bartlett pears.

1 1/2 teaspoons of agar-agar powder.

Chop the cherries and cook in a saucepan with the juice, lemon juice and sugar until the sugar is dissolved. Add the powdered agar-agar and stir until dissolved. Most recipes call for 1 teaspoon of agar for every cup of liquid. We didn’t like the texture on our first attempt—too firm, and cut back from two teaspoons to one and a half without any problem.

Leave the mixture on the stove to cool off a little while preparing the pears. Peel and slice them into thin slices. We used a small butterfly-shaped cookie cutter to cut out shapes, but the fruit can be simply diced into small cubes.

Pour a small amount of the liquid into the mold. We used a small deep serving bowl. Let the jelly set a little and then arrange the pears in a design. Keep adding layers of pear and liquid, letting each layer begin to set before adding the next, until the mold is full. Agar sets at room temperature, but refrigeration will speed the process—just don’t let it get too cold or the layers will separate.

Run a knife around the edges before removing from the mold. Agar unmolds easily, but its brittle quality doesn’t make it a good candidate for elaborate molds. The texture wasn’t quite the same, but our vegan jelly salad tasted good and captured the look of an old-school gelatin mold.