“Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity; and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life” —John Muir

A lifetime love of nature and a deep reverence for the wild led conservation-oriented philanthropists Kris Tompkins and her late husband Doug Tompkins (1943-2015), to protect more than 14 million acres of land in Northern Argentina and Southern Chile. Their ongoing project has been anchored by thinking holistically of every important facet: supporting native plants, rewilding with extirpated animals, and ensuring local communities can live healthy, dignified, prosperous lives and be invested in the preservation of their own wild land. Their approach offers a roadmap to rewilding the planet.

“Through Tompkins Conservation, the non-profit created by the Tompkinses in the early 2000’s, Kristine has been instrumental in the creation of 13 national parks in Chile and Argentina, conserving 14.8 million acres, but we see the creation of parks as a starting point,” Global Communications Director of Tompkins Conservation Carolyn McCarthy told the Topanga New Times. “As important, is to restore their ecosystems to be whole and functional, which includes bringing back missing species (13 total, including jaguars in Argentina and the highly endangered huemul in Chile) and helping local communities thrive through nature-based economies.”

Kris Tompkins says acquiring the land was the easy part. Tompkins Conservation continues to identify and remove the barriers to a thriving ecosystem. Since 1991, they have reintroduced several regionally extinct animal species, removed hundreds of miles of barbed-wire fencing, and have helped local communities thrive by supporting regenerative agriculture and ecotourism.

Doug Tompkins was the founder of the clothing company The North Face and co-founder of Esprit. As an avid nature enthusiast, ski racer, and rock climber, Doug had spent much of his life exploring the wilderness of South America and made the choice to leave the business world and purchase the land he loved to protect it. His first land acquisition in 1991 was a run-down, coastal farm in Southern Chile, which is where he began his life’s work of restoring the ecosystem of the southern cone of the continent.

In 1994 he married California native Kristina McDivitt, CEO of Patagonia, a leader in corporate sustainability. She was also a rock climber and ski racer and loved the outdoors; she grew up on her grandfather’s ranch outside of Ojai, spending most of her childhood outside in nature. She left Patagonia after more than 25 years, and joined Doug in his endeavor to restore and preserve the wild in South America.

It took many years for the people of Chile and the government to understand their philanthropic intentions. Initially, the couple’s phones were wire tapped, and the military flew planes over their land, concerned that the Tompkins might be part of a cult. Despite their early struggles, Doug and Kris acquired and rehabilitated more than two million acres and donated the land to Chile and Argentina. Most recently, the projects that Doug and Kris began in Argentina and Chile have become independent organizations called Rewilding Argentina and Rewilding Chile. Tompkins Conservation is now including seascape restoration and conservation in its ongoing work.

Doug Tompkins died in 2015, but Kris continues to be president of Tompkins Conservation and remains a strategic partner and supporter for Rewilding Chile and Rewilding Argentina.

In her 2020 TED Talk, Kris described her motivation. “From where we sat, we saw the dark side of industrial growth,” she said. “And when industrial world views are applied to natural systems that support all life, we begin to treat the Earth as a factory that produces all the things that we think we need,” she said. “As we’re all painfully aware, the consequences of that worldview are destructive to human welfare, our climate systems and to wildlife.

“Doug called it the price of progress. That’s how we saw things, and we wanted to be a part of the resistance, pushing up against all of those trends. We deployed private wealth from our business lives and deployed it to protect nature from being devoured by the hand of the global economy.”

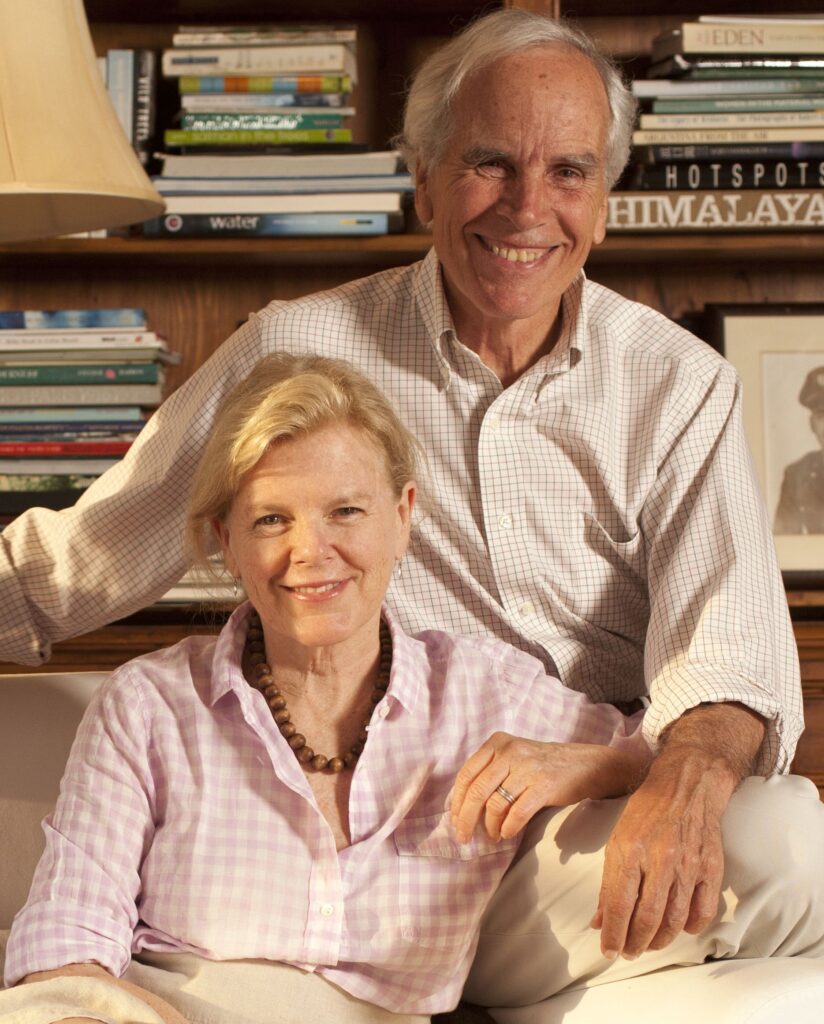

Photo courtesy of Tompkins Conservation

In 2018, Tompkins Conservation donated roughly 1 million acres to the Chilean government, prompting an unprecedented public-private partnership between Tompkins Conservation and the Chilean president Michelle Bachelet. They signed decrees to create a network of five new national parks in Chile and expand three others, adding a total of more than 10 million acres of new national parklands to Chile’s system of protected areas.

“There’s a tremendous opportunity in the US and South America for high net worth individuals to permanently protect massive areas,” Kris told journalist Brendan Dougherty during a 2020 for Forbes “It’s completely within their range of ability, and it’s not difficult to do.”

Soon after he took office, President Biden made a commitment to conserve 30 percent of American land and 30 percent of our oceans by 2030, seeking to reverse the negative impacts of biodiversity decline and climate change by protecting more natural areas. The administration has also acknowledged that economically marginalized individuals lack equitable access to green spaces. In addition to the health benefits of engaging with nature, access to nature can impact our perspective on conservation.

Tompkins Conservation, and the groundwork laid by Kris and Doug Tompkins, can help provide a roadmap for achieving that goal.

A 2015 Wildlife Society study found that the more time we spend in nature, the more likely we are to protect it. A study in England by Environment International in 2020 found a positive correlation between time in nature and pro-environmental, “green” behaviors. These studies show how national parks and other protected land can instill better stewardship of the earth. Increased access to the wild can change the way people think to use the land; not as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life.